When rehearsals resumed with the full cast, the effect of Hart’s work prompted Rex Harrison to exclaim to Andrews, “My word, you have improved!”

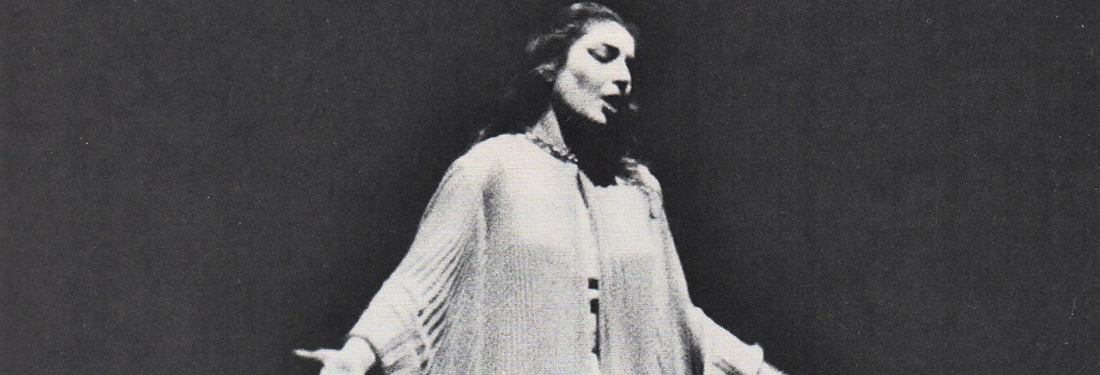

This is exactly my reaction to Sondra Radvanovsky’s singing in her new CD, recorded live in December 2019 at the Chicago Lyric Opera. In a semi-staged concert, Radvanovsky sang the final scenes from Donizetti’s operas on Tudor queens, Anna Bolena, Maria Stuarda, and Roberto Devereux.

In fact, this document may be the finest work I’ve ever heard of Radvanovsky, in what may be her crowning (sorry, I couldn’t resist!) achievement.

I was not enamored of Radvanovsky’s work at the outset in the bel canto realm. It would be disingenuously remiss of me not to mention that my standards in this genre was established by Edita Gruberova; numerous documents are out there, which reveal absolute technical precision of the scores’ demands, and indelible, histrionic portrayals, to considerable critical and audience acclaim. This is a personal reaction of course, but I need to make it clear as to why (and I am firm about declaring this).

I found Radvanovsky wanting in a few respects. Technically, I felt her overparted by the most difficult and challenging passages requiring exacting coloratura, particularly for example in the sortiti of Anna Bolena and Roberto Devereux, in addition to the florid divisions in Bellini’s Norma.

I then did not much care for her grainy, laryngeal tone; the vibrato as well seemed to hang on the underside of the pitch, accentuating the lack of squillo. Consonants came and went, and vowels were not always true to their purest values.

Too, I felt Radvanovsky’s portrayals rather placid and deficient in dramatic involvement, sometimes even timid. I felt her to be inhibited and not commanding, especially in declamatory, bold passages requiring a seizing-of in the high-octane moments.

Best example I can offer by way of comparison is of Radvanovsky, side-by-side with Gruberova, is in the all-important “Sediziose voci” from Norma; it highlights the difference between the monotonously stodgy and the vividly rapt:

However. I began warming up to Radvanovsky in the 2016 HD from the Met of its Roberto Devereux. The final scene, in particular, was stunningly acted and sung, and the soprano truly rose to the occasion.

The tide, as they say, really turned when I saw Radvanovsky in the Met’s HD of Norma in October of 2017.

I don’t know if it was the director, David McVicar, who effected this newfound change, but it seemed as if Rad had been suddenly turned loose, and a complete, alert artist, a far better, more musicianly singer, all seemed to have emerged in this production. I remember walking out of the theater completely gobsmacked and dazed at the metamorphosis I had witnessed: and she completely won me over. I absolutely love it when previous reservations are flung away. I now call myself an admiring fan.

The CD under review not only sustains that impression, but exceeds it: this is the finest work I’ve heard Radvanovsky do, not only in the Tudor trilogy, but of her entire gallery of roles. It is evident that she has not only put in the hard work and constant refining to achieve this, but it should be noted that the soprano is 50 here, and the voice is still in its prime, full, unblemished, and actually more secure than ever.

She inserts only brief sopracuti at the end of the Devereux and Stuarda scenes but not the Bolena; these are wise choices that increase respect at the behest of discretion.

The Mad Scene from Anna Bolena shows Radvanovsky consummately responsive to the shifting moods in the recitative, with a splendid high C on ‘infiorato,” and with more rhythmic impetus to the emotions of the text than I heard in the past. A few quibbles: “nozze’ and “Il re” come out as “nozzi” and “Il ri,” and the occasional consonant is fuzzy.

The “Al dolce guidami” is gorgeous, long-lined, and exquisitely shaded, and she fines down the tone most impressively without it turning white and core-less. “Cielo a’miei lunghi spasimi” is very touching, the voice soft and sweet, with the last phrase, “di speranza almen” being particularly lovely. In the following recitative “Manca solo a compire il delitto,” Radvanovsky disappointingly does not do as per the score the low C and B flat on “sara.” I sort of expect a dramatic soprano to take these notes; and as she demonstrates elsewhere, she has them, quite strong and firm; she has no need to take it up notches.

The “Coppia iniqua” begins a bit sedately, where it needs tremendous thrust, with biting vowels and cutting consonants, to convey the ‘tremenda’; as in previous outings, the ‘vendetta,’ which goes from low D to E flat-G-F to E flat, is muffled, and weak, and sounds like ‘vendeetuh’ – the word has to be pungent, and strong to express the sentiment. The trills are strong, though, as are the high Cs. She recoups somewhat for the repeat, offering some thrilling, high variazioni that effectively underlines Anna’s anger and desperation:

Of the three queen operas, Maria Stuarda perhaps best suits Radvanovsky in toto – it is absent of the hazardous florid writing of the other two roles.

Moreover, this is one of the best performances of Maria’s last half hour on record. Radvanovsky has the true dramatic soprano and grandeur of tone to fill out the Scottish queen’s 3 scenas: the prayer “Deh! Tu di un’umile preghiera—beautifully poignant, with some lines excitingly raised; the penitent “Di un cor che muore,” and most of all the concluding “Ah, se un giorno ritorte,” where the soprano effortlessly unleashes the fullness of her voice, which abets Maria’s mounting urgency with awesome, majestic power.

Radvanovsky has now in her vocal armory a much more wide range of colors and textures than she utilized in the past, and her intoning of crucial words and phrases are alert, alive, and imbued con intenzione. By the way, I am assuming the critical edition of the score, which I do not have, is what is used here; I can only say some of it sounds different than what I’ve heard in earlier performances of the opera.

The last, Elisabetta’s final scene, happens to be the best. It’s the one I go back and listen to the most, for nothing I’ve heard Radvanovsky do prior to this exceeds her performance here: and she has never sounded more vocally confident, dramatically bold, and vivid in expression.

In addition, hers may be closest to the kind of voice meant for the role: it has true dramatic breadth, able to fulfill the tonal depth, coloring and range the fiery monarch demands. And Radvanovsky has at her command, at this stage, an admirably wide ability at dynamic variety, from the softest pianissimi to ringing fortes, and what’s more, they’re not “trick” effects of separate entities, but rather, equal in value to the homogeneous whole.

The “Vivi ingrato” is just splendid, seemingly seamless in line, with exquisitely moulded phrasing, and molten gold of tone. The “m’abbandona,” which on “dona” starts at a high B, and where the line goes gradually down (marking “calando”) via a series of half-steps – A#-A-G#-G-F#, then E-D-C#-D – depicting the “sinking” despair – is magnificently negotiated. The woman, via the queen, her grief, remorse – is fully captured.

After the cannon is sounded, signaling Roberto’s execution, Radvanovsky delivers some superbly fierce, despairing accusations at Nottingham and Sara, with a truly bitter, growled, “Spietato cor,” which I find quite exciting.

The “Quel sangue”—a slow cabaletta distinguished by intervals of sevenths and tenths, and with the unusual marking of “maestoso”—is ideally realized. The soprano shirks neither the chesty low phrases at “al cielo, s’innalza,” nor the highs, which stun in their scorching power, and her strong, textual-rhythmic punch is electrifying:

The conductor, Riccardo Frizza, leading the Lyric Opera of Chicago forces, is a true ally to his star soprano: he accompanies and accentuates her singing in the most positive of ways, providing Radvanovsky with unerring support. Bel canto requires a conductor with this skill and flexibility to allow singers to breathe and phrase, while underlining the dramatic impetus, and Frizza excels at both. All the comprimario and leads roles in the scenes are cast from strength; I particularly enjoyed the Percy and Leicester of tenor Mario Rojas, who has a voice of distinctive tonal quality.

The gatefold, 2 CD set is truly luxurious packaging. The overtures to all three of the operas and choral introductions are included, which may not interest everyone, but it does capture the sense of a complete evening occasion. The booklet contains a welcoming introduction by the general director Anthony Freud, and a very warm, sincere one by Radvanovsky herself; and Roger Pines provides an engaging, fascinating history of the operas. Full texts and translations are provided.

Highly recommended, and Radvanovsky is very special here!

Comments