Here in Los Angeles, which lacks a music society benignly dedicated to the presentation of George Frideric Handel’s operas and oratorios, we wait for our yearly fix from Harry Bicket’s visit with The English Concert at LA Opera like it’s opera Easter. The Metropolitan Opera has actually mounted five Handel operas since its first (musically spurious but spectacular) Rinaldo in 1984 (thank you, Marilyn Horne). They’ve even granted Giulio Cesare a second new production (although both were borrowed). I remember vividly seeing Julius Caesar televised from the English National Opera with Dame Janet Baker and Valerie Masterson. She swanning about in those Michael Stennet costumes and looking like Vivien Leigh all over the joint. It was my first complete Handel and Ms. Masterson especially had the magic to convert.

Yet if it weren’t for the record companies, bless them, we’d hardly hear much of it. Oh sing-a-long Messiah’s abound, but The Met still hasn’t gotten around to producing what is likely Handel’s most popular work, Alcina. There are well over a half-dozen recordings and videos dating back to the dawn of time (1962) when Decca/London released La Dame Joan Sutherland’s recording ( musically spurious, but you gotta start somewhere). Our Joanie was not happy with her assigned arias and appropriated her sister Morgana’s Act One show-stopper, “Tornami a vagheggiar” for her own (as was also her wont in performance). Such a gesture was sanctioned by Handel himself in revival in 1736 (not for Joan herself), but still…meany.

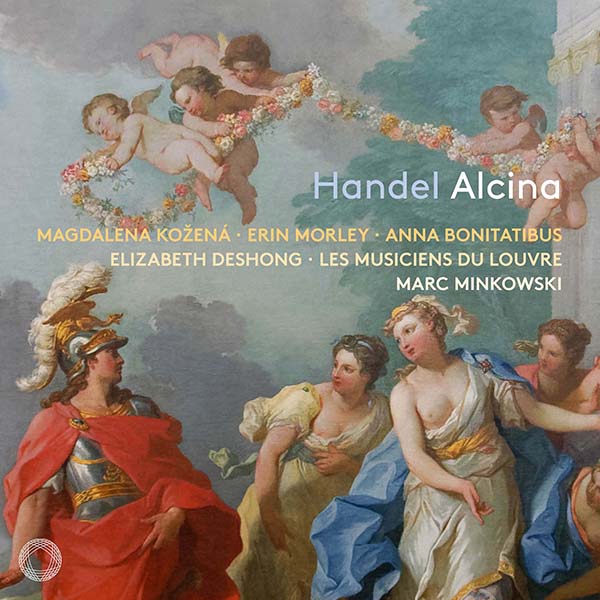

Excited was I when I heard a new Alcina was calling to us since it had been a minute since the last time we had visited Handel’s enchanted isle. When I heard that Pentatone was producing the venture with Marc Minkowski and Les Musiciens du Louvre and that taking the leading role was Magdalena Kozena I was practically overjoyed. Their recording of Giulio Cesare in Egitto, with Kozena’s resplendent Cleopatra, is my absolute favorite of that work.

The current Alcina was recorded last year February in Bordeaux around the time this same cast and conductor were performing a 6-city tour that will culminate this February with a gala performance at La Scala and the physical release of this CD (champagne corks pop in background). Downloads from the Pentatone site are already open.

The plot concerns the knight Ruggiero falling under the erotic spell of our titular intrigante. Whilst attempts to save him are made by his fiancee Bradamante (disguised as her own brother) who then, thus garbed, arouses the passions of Alcina’s sister Morgana, who’s also got a magic wand and an itchy trigger-finger. It pushes the absolute limits of dramatic credibility in true baroque fashion for three acts while nevertheless providing almost boundless opportunity for the kind of emotional swooning and blistering fury, with applicable vocal display, that Herr Handel specialized in.

Things start out well with a sprightly and danceable 3-part Sinfonia / Musette / Menuet that sets the stage for the story’s action and show’s Les Musiciens in good form with a lovely acoustic provided by the sonic wizards of the Netherlands.

It’s the kind of recording where I caught myself saying out loud, “Oh, that was lovely” at the end of most of the pieces. Sadly though, not really gripped by anything in the drama per se. I know that can be a stretch with Handel since performing his music does take a certain detachment, and with a studio recording to boot, but one can hope.

The cast is certainly accomplished but makes a slightly uneven impression. Tenor Valerio Contaldo sings the role of Oronte and I find his overuse of straight tone, in combination with his reedy sound, unfortunate. And even more so when he starts to aspirate his ornaments. His Act II “È un folle” finds him hitting all the notes with precision and speed but, sadly, without grace. Later in Act III he gets a chance at redemption with a beautiful “Un momento di contento” which is taken at a much more reasonable tempo for the singer. Yet here he’s overshadowed by the absolutely stunning work of the string section’s mirror image echo effect in their accompaniment. It’s truly something to hear.

The role of Oberto is given to countertenor Alois Mühlbacher who has an oddly sexless sound, even for a voice of his stripe. Again we have an extra helping of straight tone which of course is a stylistic choice but doesn’t charm the ear. Mr. Mühlbacher does make his best impression in the dignified first act, “Chi m’insegna il caro padre”.

The bass role of Melisso has only one air that comes in Act 2 where it seems to have been inserted to give the rest of the cast a much needed respite. Alex Rosen dispatches “Pensa a chi geme d’amor piagata” successfully enough although he’s stretched at the very tip top.

This brings us to the four principals all of whom acquit themselves commendably starting with the Bradamante of mezzo-soprano Elisabeth DeShong. I’ve been fortunate enough to see Ms. DeShong here at LA Opera as Rossini’s Rosina, Mozart’s Sesto and in this very role when The English Concert visited in 2021 with Alcina. With her opening “È gelosia,” she proves herself to be the complete mistress of her voice. Her quicksilver passagework and liquid staccato all beautifully executed. When “Vorrei vendicarmi” started in Act 2 I literally laughed out loud at the speed of Maestro Minkowski’s tempo and knew that he had met his match. Then her stately and brandy-tinged “Mi lusinga il dolce affetto” that follows is just about the most beautiful piece of singing you’ve ever heard. The rhythmic syncopation of her phrasing is so easy. I have enjoyed all of these arias countless times while writing this. We know nothing is perfect, but Ms. DeShong nearly is.

As Morgana we have the positively glorious Erin Morley who hardly needs my endorsement. She gets the whole show off to a wondrous start with her “O s’apre al riso,” delightfully gamboling and trilling about with the freedom and ease of a bird. Her “Tornami” gets a smidge wiry at the very top, but it’s a vivacious performance with unique ornamentation that absolutely delights the ear. Her “Credete al mio dolore” at the top of Act III is a particularly fine piece of singing made even more powerful by the cello accompaniment of Gauthier Broutin. What’s so extraordinary is how she constantly threads the vocal needle. My hope is that she herself will eventually inherit this magic isle one day, if you know what I mean.

The contribution of our Ruggiero, mezzo-soprano Anna Bonitatibus, is a little harder to discern. It’s a lovely, fruity voice and she certainly has excellent breath and phrasing. Her Act II “Mi lusinga il dolce affetto,” while not erasing memories of some of her predecessors in the role, is a fine piece of singing as is her very clean farewell to the island, “Verdi prati”. Her last act “Sta nell’ircana pietrosa tana” is brimming with energy but finds the voice perhaps not ideally centered over the (very) wide range called for. She also tends to less than ideal emission in the quieter parts of the role with the voice turning a mite tremulous when singing piano.

Which (or witch) leaves us with our sorceress herself the formidable Magdalena Kožená. I need to preface this by saying that anyone who hasn’t heard her absolutely spectacular Cleopatra should find the time to do so almost immediately. Back in 2012 on these pages I reviewed the CD release of her Salzburg Carmen, if you’re looking for a chuckle. Her opening “Di, cor mio, quanto t’amai” shows her pecking a bit at the music and the voice doesn’t open up and sound as fully on the topmost part of her staccato descending ornaments. During her double nervous breakdown in Act 2, “Ah, mio cor!” and “Ombre Pallide”, she pulls every baroque trick out of her purse to carry off what turns out to be a very accomplished and formidable performance. She even digs into the text with her baby chest voice for a moment, which is very exciting.

What Ms. Kožená’s voice now lacks, and it seems churlish to say this, is the innate nobility that this role requires. I’d like to blame this primarily on time’s winged chariot hurrying near. The quality of the voice has changed, not substantially, but it has changed. The attractive flutter she had has become more pronounced at slower tempos and the voice lacks some of the allure it once had. I’m sure in a live setting this would be hardly noticeable but the microphone is a microscope as we all know and the knap is off her sound. It strikes me very much like Victoria de los Angeles’s performance on the recording of the Vivaldi Orlando Furioso; a wonderful souvenir, but one wishes that she’d been discovered on this enchanted island just a little earlier.

Maestro Minkowski and his Les Musiciens cover themselves in glory from the start and, I think, this is due in no small part to the engineering of the sonic wizards at Pentatone. The playing on this recording is almost more seductive than the singing. My ear was constantly enchanted by the pre- and postludes of the arias. The dances, which I’d normally skip, were a toe-tapping delight. I had a teacher once who said that Handel’s tempos, whether slow or fast, should all be danceable and the playing here was infectiously graceful and clean and full of feeling, far more so than any recorded performance I’ve ever heard. Ornamentation throughout is tastefully taken and just once I’d love to time travel back to hear how aggressively (or not) singers in Handel’s own time embellished their performances.

I should also mention that the ad hoc chorus assembled numbers only an astonishing eight voices and they jump in for a bit at the beginning and then again at the finale. I was honestly surprised there were so few of them as they make such a wonderful sound. I did particularly enjoy that their opening piece, “Questo è il cielo di contenti ” was preceded by a few discreet shakes on a thunder sheet. Nice touch that.

I’m working off an electronic review copy, but I’m assuming this comes in Pentatone’s stylish and environmentally friendly, cardboard folder with attached libretto. I will say that, thanks to their minimalist design aesthetic, none of the tracks in the booklet are identified by aria, recit, or character name which leaves you to identify the good bits by only the length of their time stamp. Because of this, I now know Alcina far better than I ever have before. Also, there’s a wonderfully informative essay by Suzanne Aspden in the booklet. It occurred to me while enjoying it that these liner notes were the beginnings of my operatic education as a teenager for which I am grateful.

I’m far from a musicologist but I’m assuming the edition used includes all the music and recitatives because (lord help us) it stretches out over three discs and 86 tracks. In spite of its very minor flaws, this is music making of the very highest order made even greater by the flawless engineering of the Pentatone team. I bow low.

Comments