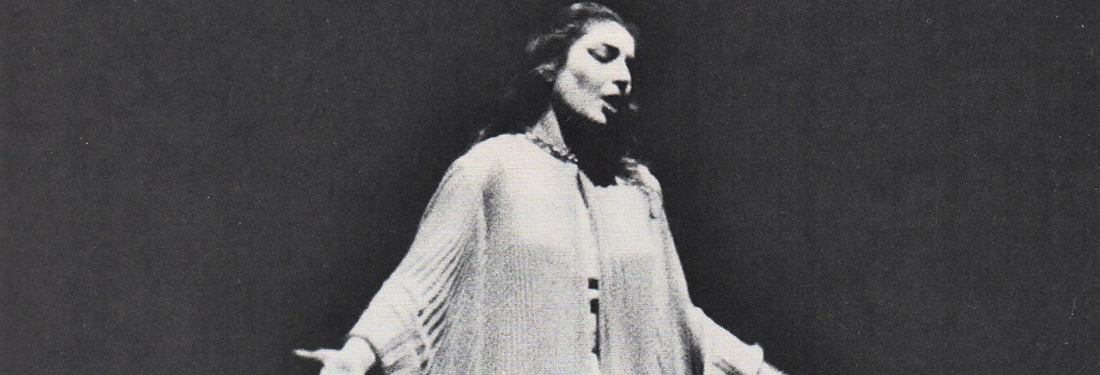

I don’t know if any of you have heard but it’s the centenary of the birth of Maria Anna Cecilia Sofia Kalogeropoulos. During her career she was known by her married name, Maria Meneghini Callas, to save on the ink for the playbills. Then, finally, after renouncing her U.S. citizenship (and by doing so, very conveniently, renouncing Mr. Meneghini as well), simply Maria Callas. She was also dubbed by some in the Italian press, La Divina for reasons that will become clear almost immediately upon listening to her sing. Or you can just call her ‘Mary’ like Richard Tucker did (just don’t let her hear you).

I’m sure I don’t need to tell any of you that she’s considered by many to be one of the greatest interpretive artists of the 20th century and holds an absolute sovereign position in the pantheon of opera singers. She recorded extensively for EMI and almost exclusively for the Svengalian record producer Walter Legge: a total of 26 complete operas and 13 recital albums. Because Mr. Legge wasn’t initially a fan of stereophonic sound, we actually have the opportunity to enjoy stereo remakes of her in Norma, La Gioconda, Tosca, and Lucia di Lammermoor.

But it’s the bootleg pirate recordings that hold a special place among connoisseurs because it’s only here that we have a glimpse at the real fire that was Callas onstage in front of an audience. We all have our favorites and I’d be ready to march into bloody battle to proclaim my absolute personal best as the relay of Norma that opened the La Scala season of 1955 with Giulietta Simionato and Mario Del Monaco under the baton of Antonino Votto. It’s the one where Callas gets applause in the last scene just from delivering the two words, “Son io”.

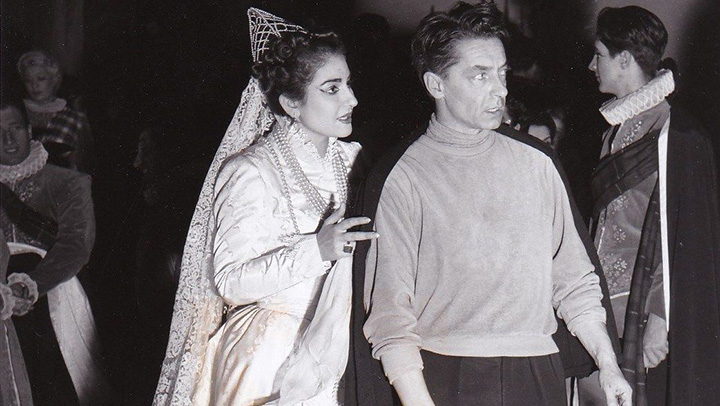

However there’s one bootleg that has perhaps the greatest pedigree of any live recording and it preserves a performance of Gaetano Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor on the evening of 29 September 1955 at the Städtische Oper Berlin. In January of the previous year, La Scala had debuted a new production of Lucia designed by the ubiquitous Nicola Benois and directed and conducted by Herbert von Karajan. The La Scala company brought their 1954 production of Lucia to the Berlin Festival for two performances and this radio relay was the opening night.

Callas had sung Lucia only a total of 14 times up until the Scala production. She debuted the role in Mexico City in 1952 and then sang it in four other productions in Italy the following year. She made her first recording of the role in February of ‘53 at the age of 30 under her early mentor, the conductor Tullio Serafin who was also responsible for her first Italian engagement as Ponchielli’s Gioconda at the Arena di Verona in 1947 (when she was 24!?).

I venture that when EMI finally started buying rights to and marketing Callas’s live performances in the early ‘90’s, the only others that joined this Lucia were the justifiably famous La Scala Macbeth (in horrible sound) and La Traviata performances from Scala and Lisbon, both of which were gaping holes in her studio discography. In 2017 EMI shored up their investment by releasing a box set of 20 complete live operas, remastered, as a compliment to their complete studio recordings box (also remastered) of three years previous. They’re now doorstops in my graciously appointed living room.

It’s important to point out that Lucia was, at the time, one of the few regularly performed operas Donizetti wrote (the others being mostly his comedies, L’Elisir d’Amore, Don Pasquale, and the occasional La Fille du Régiment). As such, Lucia was still considered a divertissement for canary fanciers. It reeked of Victorian sensibilities and its most famous exponent for years was Nellie Melba whose teacher, Mathilde Marchesi, added the famous cadenza in the mad scene with flute for her specifically.

Callas and Karajan brought a dramatic re-evaluation to the work that would break fresh ground. As a matter of fact, at the time, many critics thought Maria Callas wholly inappropriate for the Bel Canto repertoire because of her dark and over-complicated tone and the sheer size of her instrument.

Of course this would be the next step in the great Bel Canto revival that brought Callas her legendary successes at La Scala and changed our estimation of what opera as drama could be.

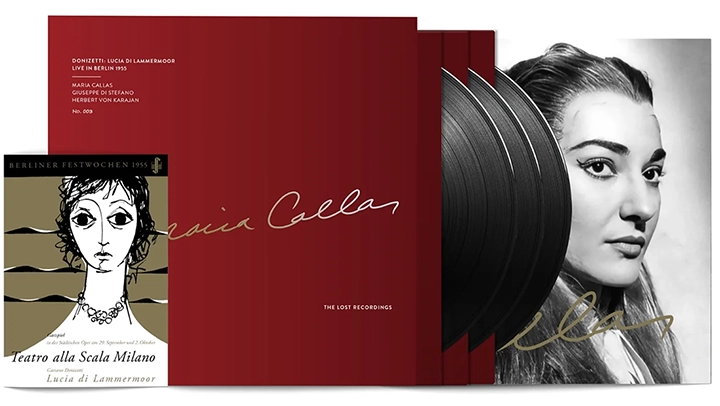

Which brings us to the release at hand by The Lost Recordings. While working in the archives of the Rundfunk Berlin Brandenberg last year, excavating important jazz performances that are their normal purview, they happened upon the original tapes of this famous Callas performance. After some meticulous clean up and not a little restoration, they’ve released them as a deluxe vinyl set, or UHQ (Ultimate HIgh Quality) CD, or as digital download just in time for the Callas hundred-hoopla. All, I might add, at extraordinary prices. You’d have to be some kind of operatic fanatic to agree to pay again ($$$) for something you’ve probably already purchased three times prior (at least!). Well, guilty as charged, your honor. Cause there’s nothing like a fresh remaster and we’re talking virgin tapes here.

This was literally the first live recording of anything I really appreciated. I became an opera fan at the birth of digital sound and I broke out in a rash if something was just mono. First off the sound, for its time, is positively extraordinary. Naturally you hear the occasional foot-fall and there are moments when some singers voices are less than optimally audible but on the whole it’s a stunning achievement for 1955. Certainly far, far better than any of the La Scala radio relays of the same era. I credit it to good old fashioned German audio engineering.

By my count EMI has remastered the same tapes now at least twice since their initial release in the ‘90’s and Maria’s last face-lift was 2017. So I sat down with my fancy headphones and compared this new release with the most recent EMI nearly track for track.

How good is the transfer you might ask? Right before the horns play the introduction to the Sextet you actually hear Maria Callas discreetly clear her throat. Not that it wasn’t there before but I’d never noticed it.

I’ve had friends joke with me that I have bat-hearing. Who amongst us has noticed that on the Karajan Decca Tosca with Price, in the last scene right after the execution, when she speaks the line, ”O Mario, non ti muovere…” there’s a squeak underneath? Literally like someone stepped on a rubber duck. Who knows what it is but it’s there. I can also spot every high note they tracked in for Kiri Te Kanawa and Elena Souliotis.

Which is why I can say beyond a shadow of a doubt that the source material here is exactly the same as the EMI and this tape itself is most definitely an earlier generation. Hooray.

At the end of the famous cadenza with the flute in the Mad Scene, there sounds like an airplane passing over the theater. You could literally hear a pin drop at that moment. The audience is sitting on their hands waiting to go insane. In this remaster it’s definitely been minimized but that sound has always been there. It starts at about the 11 min. mark on that track (queue numbers vary) and lasts about 30 seconds. Also the sound quality on the cavatina for the mad scene has always been slightly compromised from what sounds like possible wear on the tape. My guess is somebody in those archives over the years was pulling that thing out and playing it for friends.

The Lost Recordings is based in France and they have a trademarked remastering process called ‘Phoenix Mastering’ for tapes they restore which up until now have been vintage jazz concerts. This new remaster is slightly stronger, and warmer, on the bass line. Yet there’s naturally some pre and post echo on the high bits which will never go away. Generally compression is less evident and the sound is mellower and more cohesive over a broader range. I listened with new ears. I can’t say it’s worth ponying up the extra cash for something you may already own, but it is better. You can hear a sample on Instagram.

In 1955 Herbert von Karajan still had something to prove. He’d only been cleared of illegal behavior during WWII by an Austrian tribunal in 1946. He’d been conducting in Vienna and had been recording for EMI with Legge’s orchestra, the Philharmonia, in London. He’d worked his wheedles by getting back into La Scala by 1950 on a regular basis. Naturally, he was welcomed at Bayreuth with open arms.

The liner notes remind us that Karajan opened a long common cut in the stretta to the finale of Act II. Still the connective tissues of Donizetti’s score are mostly missing. A note complete recording of Lucia runs about 2 1/2 hours and this one is just a hair under 2 hours. That’s a lot of missing music. Plus, that’s with repeating the Sextet and the attendant audience applause and foot-stomping. Still the cuts are so disfiguring it almost qualifies as ‘highlights’ from Lucia.

Speaking of which, the liner notes also tell the story from Robert Sutherland’s very good book on Callas (and I can’t recall who it was on these pages who recommended it to me but Thank You) that he sat down with her one night and they listened to this performance. She recalled how furious she was when Karajan started the repeat on the Sextet and she warned him at dinner that night not to do it again.

It was the cast and Chorus from La Scala that made the trip. The orchestra used was the then RIAS Sinfonie-Orchester Berlin (Rundfunk im amerikanischen Sektor/ Radio in the American Sector) and they were founded in 1946 by the American occupation forces. Their playing is astonishingly fleet and observant.

The cast is very strong and right out of the gate you can tell it’s one of those evenings where everyone says to themselves, “I will not be bested”. Rolando Panerai comes on so hot as Enrico he sounds like a tenor. He has that little ‘Caprino’ in his throat and is holding onto every high note he gets. Sadly his opening aria is cut to ribbons and that tradition still continues to this day.

Giuseppe Di Stefano’s Edgardo is, as you’d expect, very brash but lyrical and certainly on his best behavior for Herbie vK. He’s attentive during the Act 1 duet and follows Callas’ phrasing. Later in the sextet he follows her all the way up to the syncopated high notes rather than the written harmony he’s been given by the composer. Even at that he always makes a slightly late entrance. Not necessarily lazy per se, no, just making sure he gets noticed. He’s magnificent during the “Hai tradito” and leaves blood on the wall. During the last scene he even bothers to sound like he’s stabbed himself. He manages to pull it together in the last measures so he can over-sing the final pages.

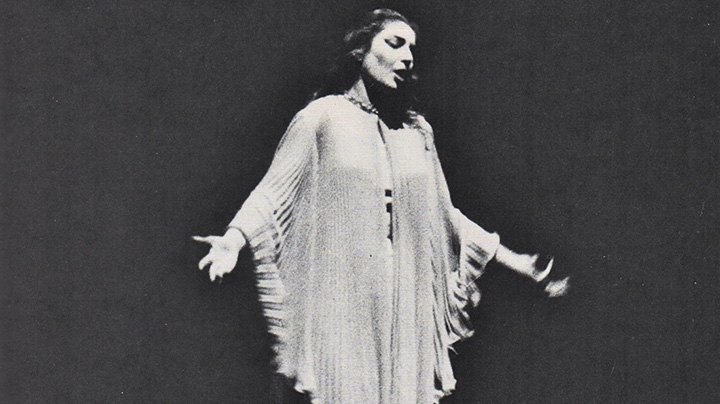

Callas recorded the role commercially twice, both under Serafin with the mono set in ‘53 and then stereo in ‘59. I’ve always preferred the second, warts and all, because of the Edgardo of Ferruccio Tagliavini who’s a far more subtle stylist. Here, in the moment, in front of an audience she’s absolutely incredible. At her entrance she’s alive during the recit with intense phrasing during the aria and bewitching trills. The delicious interplay between she and Karajan makes you wonder who’s following which genius. During the Mad Scene she’s operating on another plane entirely. It’s an absolute orgy of glissando and staccato. A veritable encyclopedia of Bel Canto technical prowess. Everyone is dazzled including the chorus, half of whom forget to come in at the final stretta. In the first scenes she hits her high notes acuti with no lower note to springboard from which is a real tightrope act. The high notes are positively monstrous all evening long. A mesmerizing accomplishment filled with more vocal subtext than the music can stand at times. Perhaps the greatest souvenir of her art there is.

To put some perspective on how great this performance really is, in June of the following year, the La Scala company played three performances with the same cast and conductor at the Vienna Staatsoper. The Vienese were so staggered that they simply closed the score on Lucia altogether. They didn’t stage it again until 1978 when Edita Gruberova proved a worthy exponent a generation later.

In that, the intrepid audio archeologists at The Lost Recording have certainly done her proud. The 3-disc vinyl edition is limited to 5,000 and will not be reprinted, making it a real collector’s item. It includes excellent liner notes, plus a facsimile of the original program. It’s priced at €228. (approx. $250). The less expensive CD comes at €58. (approx. $63) and comes in a small hardback book form with the same liner notes but no program book. You can also download in High Definition for €28 (approx $31) although I can’t speak to bitrate and I generally find downloads lacking in range of frequency. Having said that, I can’t understand the current fascination with vinyl either. Everything is pressed and bound to the absolute highest standard – I can’t recall the last time I saw bookbinding string. Then, there’s postage from France, so brace yourself.

It’s a pleasure to spend time with this performance and my estimation of it only increases with each hearing. I also can’t wait to see what The Lost Recordings have in store for us next.

Comments