Puccini’s large-economy-size Chinese game-show where local Princes compete for the hand of the Emperor’s recalcitrant daughter has always been my favorite. New recordings, be they good or not-so-much, have always brought my renewed appreciation for its incredible vocal writing and kaleidoscopic orchestrations. If only Puccini hadn’t died before finishing it. But that’s another tale.

Also, as a child of digital sound (which was glorious, but over-bright, in the beginning) the aural experience, most likely spoiled by Richard Mohr and his RCA engineers on the ‘Living Stereo’ team, has always been important to me. Some recordings are hard to abide by. Some of the more problematic are mentioned below. But all in all, Turandot, with its grand scale and the mighty forces it requires, has been uncommonly lucky on disc nearly from the beginning. Now with super high-fidelity remastering up from digital sound, and even very good analog, we have SACD (Super Audio CD) and even Blu-ray Audio that further widens out that sound palette. In some cases, it makes an enormous difference.

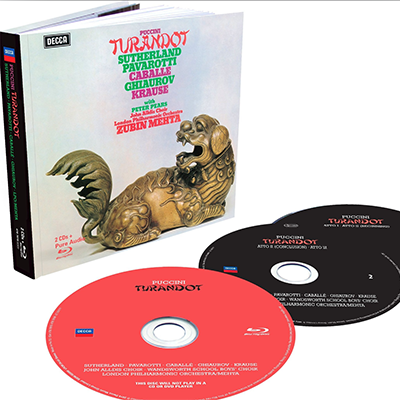

I cut my teeth on the 1972 Decca recording with Luciano Pavarotti, Joan Sutherland, Montserrat Caballe, and Nicolai Ghiarov. At the time I had no other knowledge of La Dame Joan’s prior musical achievements and didn’t understand why, when the recording was mentioned in print, it was usually accompanied by some great musical authority ringing the death knell of her voice in the wrong repertoire or at least calling it a very bad decision on her part. “At least she didn’t sing it on stage,” they’d say mopping their feverish brows like it had avoided world catastrophe. Dame Joan says in her autobiography, A Prima Donna’s Progress, (which handily doubles as a very potent sleeping elixir) that the recording was, “[a] thrilling experience and for a while I contemplated singing the role in the theater. However, after due consideration I decided to leave the public with the impression I gave on the recording of the icy princess.” I agree that the whole performance is thrilling and, with Sir Peter Pears as the Emperor Altoum and Tom Krause leading the masks as Ping, the casting is an embarrassment of riches.

The acoustics of Kingsway Hall served the original recording well from the start and when it was released on CD via Decca’s ADRM process in 1985 it sounded great. In 2014 it was remastered up to 96kHz 24-bit audio and released again in a deluxe book with the performance on 2-CD’s and complete on 1 Blu-ray audio. The upgrade is a good one although I’m not completely sold on Blu-ray audio frankly. Especially since Deutsche Grammophon mastered the Karajan Ring down to only 2-speaker stereo to fit the whole thing on one disc (boo-hiss).

An easy explanation of exactly what 96kHz 24-bit audio means is difficult without a slide-rule and an engineering degree. Suffice to say the 41kHz is considered more than adequate to cover the full range of human hearing. I have to admit I’m not sure how streaming factors into all of this as well. When it comes to downloaded FLAC and that also comes in as an option now as well. I’m listening mostly to physical media CD’s on good, big, over-the-ear, headphones unless I’m on my laptop which is streaming on my baby Bang & Olufsen speakers.

Five years later Montserrat Caballe not only recorded the leading role for EMI but sang it onstage and the keening started again from the same gallery of aficionados. Will these sopranos never learn? You don’t actually need to be a ‘dramatic’ soprano to do justice to Puccini’s vengeful Principessa, but it helps. Caballe, in spite of driving the voice mayhap too hard, was certainly capable and did sing it onstage a handful of times.

Sadly this recording was scuppered from the start with EMI’s bone-dry stereo acoustic which was their trademark for years. Unnecessarily close miking certainly didn’t help Jose Carerras or Mirella Freni, either (seriously how do you make Freni sound bad?). The current remastering on the Warner label (or anything released after 2008 on EMI) corrects a world of sins and gives us a little more distance. Alain Lombard’s conducting doesn’t do anyone any favors and if you’re a Caballe superfan you really want the live performance from San Francisco above all others (which will be discussed in another post).

The most infamous piece of casting in the title role was Herbert von Karajan’s prevailing upon Katia Ricciarelli for his digital recording (the first!) made in the Golden Hall of the Musikverein in Vienna (because it had an organ, unlike the Sofiensaal) released in 1982.

From her first RCA Suor Angelica in 1973 until the soundtrack for the Zeffirelli film of Otello (don’t get me started) in ‘86 Ricciarelli made 17 complete opera recordings of varying levels of success. Sadly, she simply wasn’t one of nature’s born Turandots even just as a studio one-off. The voice was placed so high it didn’t really have an anchor. Which is why she was to-the-Rossinian-manner-born. Her top was like threading a needle and the color tended to blanch under pressure. Find her as Rossini’s Ameniade in Carnegie Hall to Marilyn Horne’s Tancredi in 1978 and you won’t believe it’s the same singer. She should have stuck to bel canto, but the record companies wanted an Aida. Surprisingly, that did turn out to be her best recording. Also with von Karajan, she’s the most bewitching Sacerdotessa in Act One anyone has ever heard.

People tend to forget that the von Karajan project started out as a proposed film. Joseph Losey was going to direct and they petitioned the Chinese government to allow them to shoot in the Forbidden City. Even with this pedigree, and the backing of Deutsche Grammophon, the Chinese weren’t interested in the publicity or the risk of filmmakers damaging sacred ground. Italian filmmaker Bernardo Bertolucci finally won them over for The Last Emperor a few years later. So, Ricciarelli, being the most beautiful soprano alive at the moment (save perhaps for Kiri Te Kanawa), was the most obvious casting choice for cinema. Consequently, it turned out to be one of the only modern opera recordings that Karajan made without an associated production.

Barbara Hendricks and Placido Domingo remain the best reasons to enjoy this hot-house tomato. Even if Placido’s ‘Ardente’ high-C in Act Two is obviously tracked in, his singing of the role is ardente in all the right spots. Plus he’s beefier vocally and more heroic sounding than Pavarotti.

Ms. Hendricks is my favorite Liù of all. The voice might be a tad light for the theater but ironically, she was a member of the rotating casts that did perform the work in the Forbidden City in 1998 under Zubin Mehta with all that involved hoopla and laying on of microphones (although hers wasn’t the one filmed for the video release). It also spawned a documentary, The Turandot Project, which has its unintentional moments of hilarity (especially when they’re interviewing Sharon Sweet whose Principessa I would have preferred over the telecast’s Giovanna Casolla).

Hendricks finds a fragility and a strength in the part that are unique and her portrayal has many moments of grace. Plus, I’m a sucker for a fast vibrato. Also wonderful is her unjustly neglected Mimì in La Boheme that she recorded in 1988 alongside Jose Carreras (right before his leukemia diagnosis) with James Conlon conducting a fresh young cast (also for another film project – but don’t look, trust me). It’s a gorgeous performance and once again Hendricks is an uncommon flower among Puccini sopranos.

I should also mention that Barbara Hendricks details her experiences working with Karajan in her own autobiography. She pays particular attention to how horribly he treated Ricciarelli during the recording process, as if neglecting her and playing passive-aggressive would bring the performance out of her he wass looking for. It’s a sad recounting and made Hendricks wary of working with Karajan going forward.

Ruggero Raimondi is obviously taking direction from Herbie vK since there’s no other reason why he would whisper almost the entire role of Timur and the masks are all a little too German in spite of the presence of Franceso Ariaza.

The great tenor comprimario Piero de Palma deserves his own wing in the museum of the Turandot discography. Starting in 1959 he appeared in 6 recordings mostly as Pang or Pong but also as the Prince of Persia and, finally, here he’s elevated to the Emperor Altoum. I tip my hat.

Apparently Japan has gone absolutely SACD crazy and if you start shopping around you can see almost any famous recording with a boutique re-mastering up to 96kHz 24-bit and issued on Super Audio CD for a princely sum. Then there’s the shipping (whoops). I put an Ebay alert on one and finally managed to procure it without having to take out a loan. The label is called Esoteric Recordings and I can’t tell you much more about its provenance because they had the nerve to print the booklet in Japanese. Suffice to say the original DG CD release on this one which dates all the way back to 1985 sounds just fine for all normal purposes. The new re-mastering is good but it’s not all that.

This brings us to Birgit Nilsson. Turandot was a curate’s egg and rarely performed with any kind of regularity until Birgit showed up. She once said candidly (and she was nothing if not candid) that, “Isolde made me famous but Turandot made me rich.” She also referred to Turandot as her ‘vacation’ role since it required the least amount of singing of any part in her repertoire. It also may be her best documented role: two assumptions in the studio and then a long trail of live relays stretch out behind her like a conqueror.

She made her La Scala debut on opening night 1958, the first non-Italian afforded that honor, opposite Giuseppe Di Stefano and Rosanna Carteri under Antonino Votto. Apparently full-grown Italian men were weeping in their seats from the overwhelming glory of her voice. The Nicola Benois production didn’t hurt either and she had a costume in Act II with a 30-ft. long train to drag up those stairs. The 1964 revival with Franco Corelli and Galina Vishnevskaya has been enshrined in a deluxe ‘La Scala Memories’ hardback book with photos and a middling transfer for its time.

In February 1961 the Metropolitan Opera mounted their first production in 30 years designed by Cecil Beaton and directed by Yoshio Aoyama (although Nathaniel Merrill took over due to illness). Franco Corelli was the Calaf and Anna Moffo sang Liù with Leopold Stokowski making his Met debut on the podium. Dimitri Mitropolous was initially to have conducted and his unexpected death the previous November facilitated Stokowski’s taking over (and with a broken hip on opening night). The Saturday matinee broadcast (which used to require a sizable donation to the Met Guild) is now part of Sony’s “Birgit Nilsson; The Great Live Recordings” boxset. This production caused such a sensation that it was performed over 100 times through 1974 and nearly 30 times with Nilsson in the cast. Its popularity was so great that it was rumored that Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer actually bought the screen rights with Leontyne Price penciled in as Liù. Imagine.

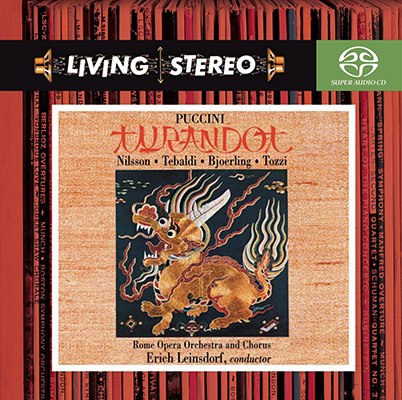

Nilsson’s first studio recording was in 1959 on RCA ‘Living Stereo’ with her great compatriot Jussi Bjorling as Calaf in his last operatic recording before his untimely death at age 49 due to a heart attack. RCA and Producer Richard Mohr wanted to show off their new toy (and out-’Sonicstage’ John Culshaw) and consequently staged the performance from some rather odd angles for the listener.

Nilsson is seemingly holding back for the microphone (understandably because one wag said that recording Birgit Nilsson in a studio was like “driving your Porsche in the backyard”). Plus, I need to final say out loud, her Italian can be heavily accented depending on the performance you’re listening to; “Qvel grido e qvella morte!” (Eva Marton, I’m looking at you, too).

Nilsson recounts in her autobiography (which is so chatty it’s like having coffee with her) that Renata Tebaldi arrived unprepared and seemed “astonishingly uncertain in the role” of Liù, requiring two coaches constantly to keep her on the correct pitches and rhythm. This is particularly odd since, although Liù didn’t factor into Tebaldi’s stage repertory, she had just recorded it three years prior for Decca with Inge Borkh and Mario Del Monaco. Still, Tebaldi’s is not a great performance on this recording for whatever reason and she does indeed seem to lack certainty in her singing.

Erich Leinsdorf, who was RCA’s go-to opera conductor, puts the Rome Opera Orchestra and Chorus through their paces and the timpani is highlighted. The chorus, going for that ‘barbaric’ vibe, does some very empathic singing. You can tell they’re not British, that’s for sure.

Nilsson’s second studio effort was in 1965, again from Rome this time opposite Franco Corelli, one of the few tenors who could hold their own vocally against her, and their pairing was legendary. They also recorded Tosca and Aida together and they performed together at the Met 43 times in those three operas. The hoped-for frisson between the two of them is in little evidence and this may be the fault of their conductor, Francesco Molinari-Pradelli, who really seems content keeping everything and everyone together (no small feat, that).

Liù was entrusted this time to Renata Scotto, then only 31 years old. She’d been singing professionally for well over a decade and had already recorded Lucia, Traviata, Boheme, and Rigoletto (twice) all for DG. Dramatically, the character doesn’t really have much to do except sing beautifully and make ‘la bella morte.’ Scotto lavishes all of her considerable gifts on a role that finds her wiry on top but very determined – and surprisingly expansive – of phrase.

Once again, we’re scuppered by the operating room acoustics of EMI and it’s astonishing when you set the RCA and EMI beside each other and try to imagine they were recorded in the same venue. The EMI engineers don’t even come close to capturing the great Swedish ice-pick in full cry, let alone Correlli at his maximum vibrancy. Again, the Japanese come to the rescue courtesy of ‘Tower Records Definition Series’ with an SACD/DSD hybrid that goes a very long way towards expanding out the previously constricted sound on this recording. It’s odd to see the Tower Records logo back in play anywhere but I was grateful to hear this recording sound so much better than before.

Of course the primary attraction to hearing La Nilsson in the studio is the fact that you get to hear the opera complete, unlike in her live recordings. As we all know, Birgit liked to make her ‘vacation role’ even shorter by omitting ‘Dal primo pianto’ in the last act, her excuse being that it wasn’t written by Puccini, despite the fact that the libretto was completed before the composer’s death and that this crucial moment, which brings about the character’s complete metamorphosis, makes almost zero sense with the aria excised.

When Nilsson sang Turandot at Covent Garden under Charles Mackerras in 1967 they were criticized for not only doubling ticket prices for the run but Mackerras himself was taken to task in the press for allowing Nilsson to cut the last act aria. He explained in a later interview that Covent Garden ‘bought’ Nilsson’s performance. And who was he to argue?

But by far the best discovery I made was the remastering of Maria Callas’s studio recording on the label Pristine Classical, and this one is a doozy. I don’t know what they did, but it certainly beats the last round of Warner Classics issues (which I thought were excellent). Mono sound always favored the voice over the orchestra for some odd reason. Here that seems to be balanced out a lot better, with the voices moved back a tiny bit into the overall sound picture and the orchestra spread out behind. It’s almost like a veil has been lifted off of Tullio Serafin’s work, as well. The most striking thing is his use of rubato and rallentando and it’s a surprise to the ear.

The detail in Callas’s singing comes forward even more. Plus, getting the full measure of his performance now, I don’t feel as bad for Eugenio Fernandi’s Calaf as I used to. I might even end up liking Elizabeth Schwarzkopf’s Liù although that might take some doing considering her Viennese-school slipping and sliding around on the notes. For fans of this recording, it’s well worth acquiring.

My little-engine-that-could recording is the one RCA released in 1993 with Eva Marton’s second assault on the title role. She’s loud but luckily not as distressed sounding as on the EMI Götterdämmerung (whoops). What makes this one special is the young Ben Heppner as Calaf, who’s a little square of phrase but ringing in the right spots. Plus Margaret Price as Liù may be just past her shelf date, but still has a lot to offer in a role where a gorgeous voice is half the battle. Roberto Abbado leads the Munich Radio Orchestra and their playing is luscious.

Now the last recording is a mystery. I read a rumor long ago that Decca made a live recording of the Metropolitan Opera performances in Sept/Oct. 1997 with Jane Eaglen, Luciano Pavarotti, and Hei-Kyung Hong under James Levine. Since I attended one of the performances, I was mighty interested. A few years later I actually emailed Decca about it and the response back from them congratulated me on my sources and said that everyone involved had signed off on the recording and it was awaiting a release date. Twenty-six years later, nothing, and Pavarotti passed in 2007, so every time I saw a new Decca release of his since (and there have been quite a few), my heart would skip a beat. Reaching out to them again when I started working on this piece, the response was that no evidence of the recording exists and referred me back to the Met. I haven’t reached out to them as yet. Another riddle.

Comments