The Italian-born French composer Jean-Baptiste Lully left an indelible legacy in the evolution of French Baroque opera, having pioneered the five-act operatic form recognized today as the tragédie lyrique. Inspired by stories from mythology and classic epics, these dramas are structured around expressive récits and airs that are interspersed within orchestral passages and the lilting dance music favored by the royal court. Lully’s genre would dominate the creations commissioned by the l’Academie Royale de Musique (today’s Opéra National de Paris) for over a century, with the art form finding its apogee in the harmonically innovative stage works of Jean-Philippe Rameau.

Jean-Baptise Lully’s prolific tenure as superintendent of music in Louis XIV’s court was noteworthy for his collaborations with the French dramatist Philippe Quinault. This artistic partnership yielded twelve out of the composer’s fourteen operas, of which Armide, Alceste, and Persée have gained prominence in the modern baroque canon. Atys, their fourth collaboration, earned the moniker “the King’s opera” due to the monarch’s deep admiration for the work. Premiered in 1676, Atys would grace stages more than ten times during the Sun King’s long reign and would experience at least eight more revivals before falling into obscurity during the second half of the 18th century.

Louis XIV’s affection for Atys is unsurprising, considering its thematic traversal of the complexities of unrequited love within the merveilleux of mythology. The libretto depicts the tragic romance between the beautiful youth Atys and the nymph Sangaride, who are entangled in the power dynamics orchestrated by the goddess Cybèle and the Phrygian king Célénus. At the beginning of the opera, Sangaride is betrothed to Célénus, while Atys is entrusted the guardianship of Cybèle’s temple as part of the goddess’s ploy to earn his love. Upon discovering the couple’s deceit and affections, Cybèle drives Atys to madness and causes him to murder Sangaride. In a moment of despair, Atys commits suicide, prompting the remorseful Cybèle to immortalize him into a pine tree as a symbol of her enduring love.

Atys’s significance as a work of dramatic theater was realized in modern times by our era’s preeminent baroque musical archaeologist William Christie. In the late 1980s, Christie and his baroque ensemble Les Arts Florissantsmounted Jean-Marie Villégier’s stunning production of Atys at the Opéra-Comique, revealing to modern audiences the dramatic potency of Lully’s theatrical oeuvre. Its first studio recording by Harmonia Mundi soon entered the discography, followed a quarter century later by the ensemble’s equally lauded revival of Villégier’s legendary production in 2011, lovingly underwritten by the late American businessman Ronald Stanton.

All these incarnations of Atys, available either in CD or recorded video, are commendable for introducing the musical and dramatic riches contained within Lully’s opera. However, if one must choose a historic document that representsAtys at its dramatic and musical finest, this vintage 1987 video filmed from Montpellier–featuring Howard Crook’sravishing Atys and Nicolas Rivenq’s commanding Célénus joining the superb cast from Christie’s recording–may be as definitive as a performance can get, especially if the original tapes are remastered in pristine sound.

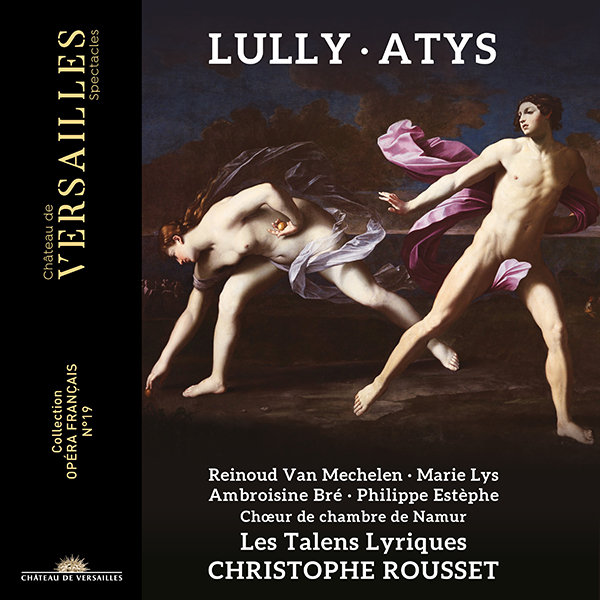

Nearly four decades after William Christie gifted listeners with the 20th century’s first Atys, Christoph Rousset and his orchestra Les Talens Lyriques have created the opera’s third studio document on the Château de Versailles Spectacles label. Acclaimed for his interpretations of baroque opera, Rousset’s impressive discography includes Decca’s superb period reading of Mozart’s Mitridate, various studio and live operas by composers as varied as Rameau, Salieri, Cimarosa, Handel, and Monteverdi, and rare French gems unearthed by the Bru Zane label (e.g. Spontini’s La Vestale with Marina Rebeka and Stanislas de Barbeyrac). While Rousset’s artistry in this repertory is remarkable, his most singular contribution to the discography arguably lies in his extensive and ongoing survey of Lully’s major operas.

Atys’s music was critical in shaping Christophe Rousset’s artistic career. In the late 1980s, he became the harpsichordist and chief continuo player for William Christie when Les Arts Florissants prepared their groundbreaking production of the opera. After decades of resurrecting Lully’s other operas for contemporary audiences, Rousset returns to the score that exposed him to the vast expressive possibilities of the composer’s theater.

In this latest recording, Rousset and Les Talens Lyriques capture Atys’s dramatic flow and rhythmic pulse with vitality and élan. Another striking feature of this set is the clarity of the orchestral image–Rousset’s characterful instrumentalists enliven the divertissements and ritournelles with vibrant coloration, while his continuo underpins the narrative’s progression with a persistent dramatic presence (how the bass line clearly reflects Cybèle’s rage in Act 5!). Under his direction, the ensemble masterfully infuses Lully’s kaleidoscopic third act with its full range of atmospheric richness while capturing the dramatic frisson and the funereal beauty of the lamentations that conclude the opera.

For this new Atys’s cast, Rousset has rounded a group of idiomatically capable soloists to play Quinault’s quartet of leading characters. Playing the titular role is the Belgian tenor Reinoud Van Mechelen, a haute-contre specialist who fluidly negotiates the part’s vocal writing and dramatic palette. While a gritty ungainliness can occasionally creep into his instrument’s lower half, Van Mechelen can also summon sweetness and repose for his amorous interactions with Sangaride and Atys’ beautiful Act 3 solo “Nous pouvons nous flatter de l’espoir le plus doux.” Van Mechelen’s idiosyncratic vocal qualities would prove advantageous in the story’s latter arc when the character daringly abducts Sangaride from Célénus in Act 4 and pleads Cybèle for clemency in the intense final act.

Atys’s paramour Sangaride is performed by the Swiss soprano Marie Lys whose gorgeous timbre and textual clarity can almost make one momentarily forget the inimitable Agnès Mellon. Lys’s radiant soprano charms and captivates the listener, particularly in Sangaride’s duet with Atys “Peut-on être insensible aux plus charmants appas” and her beautiful air “Atys est trop heureux.” Despite Sangaride’s less prominent role in driving the narrative, it is Marie Lys in this recording who consistently captures the beauty and pathos in Lully’s airs and ensembles.

Célénus and Cybèle are unfortunately more of a mixed bag. Philippe Estèphe’s baritone lacks the firmness of vocal production, the timbral weight, and the authoritative ring that would present Célénus as a credible monarch, much less a demigod offspring of Neptune who can negotiate alliances with the imperious Cybèle.

Ambroisine Bré, a mezzo soprano who features in many of Rousset’s Lully recordings, certainly possesses an attractive and rich tone and largely succeeds in portraying the goddess during her more introspective passages. However, Bré’s instrument is compact and could become twittery, breathy and unfocused when the vocal line ascends or demands volume. For example, while Bré connects intimately with Cybèle’s introspective “Espoir si cher et si doux,” her preceding recitative “Qu’Atys dans ses respects” lacks the puissant stateliness to drive her character’s more turbulent outbursts.

Many of the final act’s tension ridden confrontations are slightly undercut by the limitations of Célénus and Cybèle’s lighter voices, although to Bré’s credit she acquits herself with a closing lament (“Que le malheur d’Atys”) imbued with gravitas. Given Célénus and Cybèle’s centrality to this ambitious project, one would have hoped that Rousset’s second couple could have been portrayed by Edwin Crossley-Mercer and Ève-Maud Hubeaux, who were both so charismatic and vocally resplendent as Jupiter and Io in his Isis.

Notable among Rousset’s supporting characters are Romain Bockler, Gwedoline Blondeel, and Apolline Raï-Westphal, who bring to their characterizations of the siblings Idas and Doris and Cybèle’s confidante Mélisse full tones and an expressive alertness. Much credit must be accorded to the god of sleep Sommeil (Kieran White) and his sons (Nick Pritchard, Olivier Cesarini, and Antonin Rondepierre), who transform Lully’s ethereal dream sequence in act 3 into an exquisite exercise of vocal painting and tonal blending. Rousset’s direction of the Chœur de chambre de Namur, as in their previous Lully collaborations, presents the Greek chorus like scenes stylishly, if lacking slightly in the dramatic urgency that Les Arts Florissants’ choral forces underlined in their recordings.

Rousset’s chronological separation of his Atys from the genre’s early years of discovery has reaped a refreshing interpretation that is deeply rooted in his patronage of Lully’s oeuvre. In a recent interview discussing these projects, Rousset remarked of his Atys, “I think that great masterpieces need to be visited as much as possible and by as many performers as possible in order to grow…I don’t claim to have the truth, but it is my truth. So this hopefully will give a very different Lully, in any case very much in line with what I do with the other Lully’s and at the same time an Atyscompletely different from the other proposals which have been given until now.” And what a sonically fascinating and vibrant Atys it is! Rousset’s instrumental and rhythmic vitality unveil the vivid contrasts contained within this score, and barring minor exceptions, the cast faithfully executes Rousset’s vision for fleshing out this engrossing work of theater.

Comments