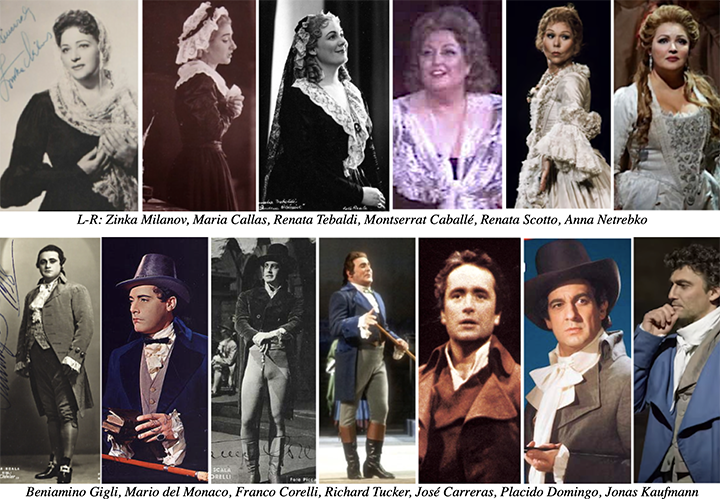

Granted, there are singers who can handle other kinds of music that the golden-age-of-the-mid-20th-century-singers could not – specifically baroque, maybe even Mozart. Styles change from generation to generation. It made me wonder how today’s youth – that for me would mean Millennials, Gen Z, and probably even Gen X – react to Gods and Goddesses of the 1950s and ‘60s. I write a lot about the singers of my generation and VERY strongly feel that there are no singers in the last few decades that begin to compare to them: Tebaldi, Milanov, Sutherland, Nilsson, Price, Rysanek, Farrell, Corelli, Bergonzi, Vickers, Warren, Ghiaurov, and a few others at the top of the list. I suppose more recently, Jessye, Pavarotti, and Domingo can be included. These singers sang with intensity, personality, and individuality which is something that is lacking in almost all singers today. Every generation has their idols from the past. My father used to go on – rightfully so – about Caruso and Flagstad, though he also adored Tebaldi and Dame Joan. Yes, there are many singers I like today: Jaho at the top of the list, occasionally Netrebko. But mostly they just don’t compare. I put it out to someone who I know is out of the Gen Z generation – unfortunately the only person I know anywhere close to that generation who actually likes opera. Can they feel the same way about my gods and goddesses?

Apparently, the short answer is no. His feeling was that his generation does not feel such attachments. His hypothesis is that it is a result of a very different relationship to music in general and recorded music specifically. In his case, he uses a recording to get to know a work but prefers to experience it live. He has the advantage of living in a major city with easy access to musical events. He adds he doesn’t have the patience to engage with recordings as previous generations did. He sees it as over-stimulation; I would see it as a lack of attention span … the ability to and the patience for sitting down with a recording with or without a score or libretto. I can empathize with that, as my eyes generally need something to see and fingers something to do otherwise I doze off – sadly that’s more of an age thing. The closest he got to my intended question regarding the singers specifically was that he could appreciate singers like Tebaldi and Callas. Ultimately, though, he cared about the pieces themselves rather than the interpreters though he certainly appreciated that operas don’t exist without the singers that perform them, trying not to put any singer in front of us today at a disadvantage compared to someone who’s long dead in order to see the positives in those singers.

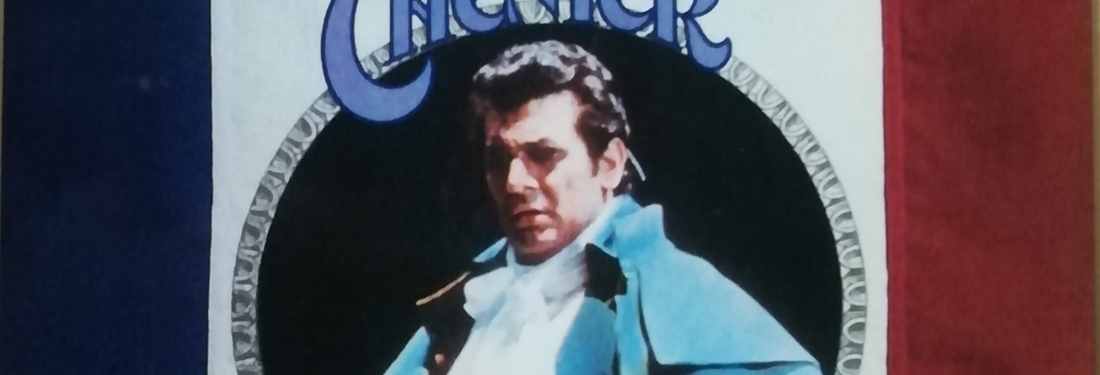

My generation of baby-boomers had a clear advantage of real super-stars, legends in their own time. That was not only in the opera house, but on Broadway and Hollywood. It was a Golden Age of Opera and the end of the Golden Age of Musicals and arguably just past the Golden Age of Hollywood. More importantly, I have always been and always will be a strong believer that Opera, first and foremost, is about singing; what is being sung follows. Getting to the point – finally! – I believe that Andrea Chénier is appreciated for the great moments that it offers singers rather than any great moments of music. Chénier stands of falls by its three principals. Okay, I exaggerate – a bit.

The first thought I had when it came time to writing was to check all the recordings I had of this specific opera (19 complete) and then check to see what OperaOnVideo had – 132! Of course, I realize that only half of those are complete performances and that half of those are actually there and haven’t been taken down; but still, that’s a lot for a not very highly regarded opera. Mercifully, I didn’t listen or watch all of them and I’m not going to discuss all of them either. I’m sticking to what I think is a significant recording (studio) or performance (live) and then what’s hopefully available.

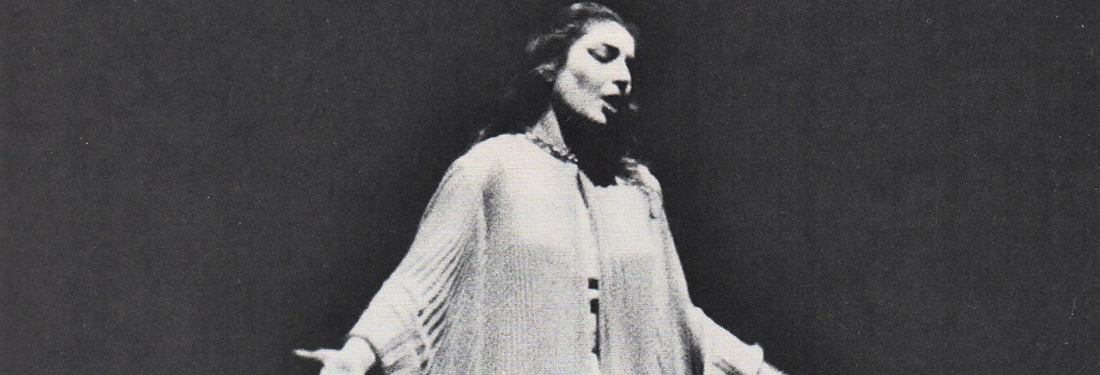

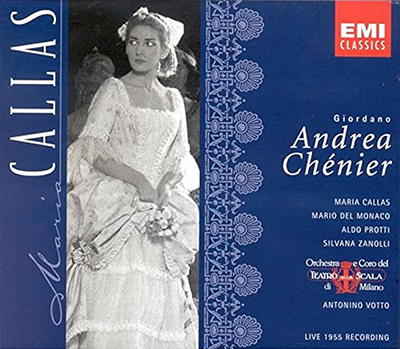

A good place to start is with the most famous recording of Chénier even though it is of only Maddalena’s aria, “La mamma morta.” I have already referred to it: Maria Callas’s heartrending performance that Tom Hanks “analyzes” in the Oscar-winning Philadelphia. Callas sings the aria with great potency and a mastery of vocal color and inflection surpassing all others, even though those others do, as usual, sing it with a greater beauty of voice (not necessarily a prime requisite for this aria). Callas sang only a handful of performances during one run of the opera at La Scala. Originally, the opera was supposed to be Il Trovatore but Mario del Monaco begged out claiming that Chénier was easier(?) than Manrico. More on him later. Callas learned the role in a matter of days, never recorded it commercially other than the aria, and never sang it again. I was surprised at how much I liked the recording of the complete live performance, now released commercially by EMI. In fact, I would claim it as her finest live performance, at least the equal to her Gioconda. Simply put, it is a great performance. At this point, 1955, she was at her height, everything in place. She sang Maddalena in January; followed that in March with the Sonnambula with Bernstein and followed that in May with the Giulini/Visconti Traviata. Quite a year!

With Hanks (1993 movie Philadelphia):

Without Hanks (1954 EMI studio):

Callas live 1/8/55 La Scala:

Backtracking, the first complete recording of the opera was in 1931 on EMI with Marini, Rasa, and Galeffi with Molajoli conducting. I have not heard it. Far more important, is the 1941 EMI with Beniamino Gigli, Maria Caniglia, Gino Bechi with Oliviero de Fabritiis conducting. Gigli was 51 at the time of this recording yet he is at his most inspired. It offers proof that he might just have had the century’s most beautiful voice. On the other hand, it’s argued that his overbearingly demonstrative performances for lyric roles was balanced by his unimpressive assaults on heroic ones. Gigli’s voice here, though, is a combination of lyricism and a ringing heroic sound. Many feel he is the ideal and best Chénier. Maria Caniglia starts with a light, girlish tone that gains weight before becoming a bit squally in the final duet. Gino Bechi can be described as a provincial baritone – which is not a bad thing for this role. He didn’t perform much outside Italy, but he was a star dramatic baritone doing all the big Italian parts in all the Italian houses, as well as doing lots of movies and pop-crossover discs. He was famously the Nabucco to Callas’s legendary live Abigaille in 1949.

Zinka Milanov’s most iconic roles were the three Verdi heroines: Aïda and the two Leonoras, Gioconda, and Maddalena. Surprisingly, while she recorded the first four, she never commercially recorded Andrea Chénier. The Met made up for that with three broadcasts, the first of which was released as one of their first Historic Commemorative deluxe albums. My preference is for the second broadcast, the one with Richard Tucker. Both Milanov and Warren were new to their roles, but their performances aged well and both were still at their peak in 1957. Strangely, in the 1953, Milanov got next to no applause following “La mamma morta.” In 1957, she took the higher ending and the ovation was extensive. 1963 she was well past the sell-by date. Besides these three broadcasts, she celebrated her 25th anniversary with the Met with Andrea Chénier and she chose the opera for her farewell performance in April of 1966 though she followed that three days later for the final performance of the Old Met with the final duet with Tucker. The review as reprinted in the Met archives wrote:

On Saturday night, Mme. Milanov will be joining with her colleagues in their musical farewell to the “old” Met, but last night was her night and an occasion for a bulging houseful of cheering, applauding and weeping admirers to let the illustrious Yugoslavian soprano know what she has meant to them through the past 28 years. In any season, the departure from the operatic scene of a star of Mme. Milanov’s magnitude would be cause for nostalgia and regret, last night, she received a series of show-stopping ovations culminating with a seven-minute outpouring of affection, following her third-act aria, “La mamma morta,” which has had few parallels in the history of the house. Despite the obvious emotional demands of the evening, Mme. Milanov performed, as she has always performed here, with the grandeur and authority reserved for the phenomenally gifted few, and it wasn’t sentiment alone which told everyone present that they will never hear and see anyone quite like her again.

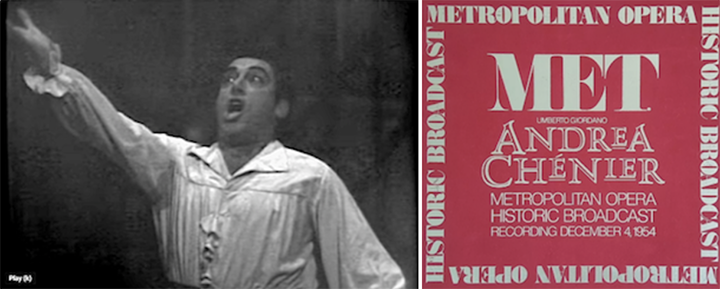

In the 1954 broadcast, Mario del Monaco overwhelms the performance as he was prone to do. Loud and unsubtle. And undeniably exciting. In earlier performances, he did modulate his tone, but generally it was very monochromatic. He was lucky to have sung the role with Callas, Milanov, and Tebaldi many times. There are also videos with Tebaldi and Antoinetta Stella. I ask, just how many times in one aria can he thrust his arm to the balcony?

MET 12/4/54 (live) – Del Monaco, Milanov, Warren; Cleva

Leonard Warren undoubtedly has the finest voice of any dramatic baritone, the most aristocratic, but Gérard is not an aristocrat and that is why I said earlier that Gérard can best be served by a more provincial baritone. Unfortunately, I cannot find any photo of Warren as Gérard. Standouts among the excellent supporting cast are Rosalind Elias as Bersi, Sandra Warfield as Madelon, Salvatore Baccaloni as Mathieu, and Alessio de Paolis as Incredibile.

MET 12/28/57 (live) – Tucker, Milanov, Warren; Cleva

Lucky is the soprano who gets to sing the final duet, “Vicino a te,” with Tucker, Del Monaco, and Corelli. Or is lucky are Dick, Mario, and Franco to get to sing that duet with Renata Tebaldi? Actually, I think it is lucky us who got to see all three versions on television! The first pairing showed an obviously very nervous Renata (that arm never left her back) with a much shorter Tucker on the Ed Sullivan Show in 1957. The singing is as lush as can be imagined. The duet is somewhat cut. An even more exciting version with the two R.T.s is sung at that legendary Chicago concert with Georg Solti conducting (the same one when Tebaldi sang the Gioconda duet with Simionato)

The 1961 version is from a complete(!) Chénier when La Scala visited Tokyo. Yes, complete. Tebaldi actually had FIVE complete operas on video (that Greek singer only had one measly act! … but what a whopper that ‘one measly act’ is: the legendary ROH/Zeffirelli Act II of Tosca) – two Toscas, an Otello, Forza, and Chénier. Truth be told, none of those videos are particularly flattering. It wasn’t till the mid-60s that Tebaldi glamorized herself and learned to act. One can see that in the 1966 video with (finally someone taller than her) Corelli, also on the Ed Sullivan Show, a tie-in with the opening of the new Met when they were both singing in the new Gioconda.

A very nervous Renata… “This is MY opera!”… Mr. & Mrs. Opera

Tebaldi & Tucker – Ed Sullivan Show 3/10/57

Tebaldi & Del Monaco – Tokyo 1961

Tebaldi & Corelli – Ed Sullivan Show 9/18/66

The sheer tonal weight of her voice is found ideally in Tebaldi’s singing. That voice was eminently suited to Maddalena’s music, a part that she could imbue with her meltingly limped tone and over time bring to it her ever-expanding dramatic awareness and developing chest register. Her first Chénier was at the beginning of her career in 1945 in Parma and her last in 1970 at the Met, close to the end of her career. Over that time, her conception of the role, at least vocally, changed radically, sometimes out of necessity but mostly because of her growing art. Strangely, though, her best balance of singing was at the very beginning – the late ‘40s – early ‘50s. The voice, being younger, was much lighter, no problems with pitch or high notes, but it was the dramatic inflection that she brought to the music that was so different. I was well aware of this from the legendary 1953 Forza. In my research for this essay, I came across a recording of, unfortunately, only highlights of a Chénier from 1949 with Tebaldi that is simply mind-boggling. She is a revelation here. The same goes for Del Monaco – he actually sings tastefully at times. In many respects, it is the both of them at their inimitable bests. As Mitropoulos performed miracles for them in that Forza, Victor De Sabata does the same in this Chénier. Fedora Barbieri is the Madelon. Spoiler: the last act is missing – eek!

All together, I have found 12 complete performances of the opera with Tebaldi including two studio ones. All of them can be found online. The first studio is from 1953 on Cetra (or Everest or whatever it was called then) with José Soler and Ugo Savarese. It’s unfortunate that the singing of the two gentlemen is nowhere near the quality of the prima donna, but that prima donna’s performance is a revelation if you’ve only heard her in the 1957 Decca. That more famous recording tied in with her one performance of the role in the same month of her Met debut, again with Del Monaco and Ettore Bastianini. As he turned out to be the best Barnaba, Bastianini is also the best Gérard. He brings a robust and spontaneous interpretation which is made more impressive than most other baritones because there is more variety of nuance and coloring. Tebaldi and MdM just don’t bring to the studio what they could to the stage. Most of the time … the ’61 Tokyo video betrays that. Obviously, the two of them had not gotten the memo that opera singers now also had to act. Yes, this is clearly the tenor’s opera and Mario makes sure everyone knows that. Most appalling, in the final act, following his aria and just before his imminent death, he leaves the stage as mandated but steps back out to walk down to the footlights for a bow … TWICE! Disgrazia! Okay, it was a different era.

Far more important are the two Met broadcasts neither of which disgracefully have never shown up on Sirius nor on Met on Demand. Neither have four other of Tebaldi’s Met broadcasts (out of 18) which, along with the two Chéniers, include two Otello’s (Desdemona, her signature role), the first Manon Lescaut, and, maybe not her best but certainly her most exciting role, Fanciulla. The six of them and the Tosca with Tucker and Warren constitute her best Met performances and it is inexplicable that they have not resurfaced legitimately; they are online, however. When I started this essay, I knew well before reaching the end of it that the two Met Chéniers would not be bettered. So, I started with the earlier performance with Tucker and Bastianini from 1960 which is arguably better sung and that I would end with one of the most thrilling performances ever to come out of the Metropolitan Opera House, the 1966 with Franco Corelli and Anselmo Colzani (who was replacing Tito Gobbi). In his “authorized” biography of Tebaldi, the obviously prejudiced Kenn Harris states that in his opinion “that it was the single most exciting performance that I ever witnessed at the old Met” and Harris again says elsewhere in the book that “it stands out in my memory as quite the greatest performance of an Italian opera that I have ever attended.”

Even individually, Tebaldi and Corelli were the hottest ticket at the Met; together they were combustible. Bing called her “Miss Sold-Out!” For once there was a tenor who looked the part … and was taller than Tebaldi. He was the perfect Andrea Chénier, ideal as the romantic idea of the heroic, self-obsessed poet. Together, he and Tebaldi, termed Mr. and Mrs. Opera, sang Adriana, Forza, Bohème, Tosca, and Gioconda. It’s a tragedy that they never did Fanciulla together. It would seem logical that the ideal cast for Chénier would be the 1960 Vienna performance widely available with Tebaldi, Corelli, and Bastianini, but it strangely falls flat. Though Bastianini has to be sacrificed, stick with the 1966 Met. It will be my No. 1 choice for a live performance.

MET 3/26/60 (live) – Tucker, Tebaldi, Bastianini; Cleva

MET 2/5/66 (live) – Corelli, Tebaldi, Colzani; Gardelli

Next time, I’ll touch on some other recordings of Andrea Chénier, some essential and others, not so much…

See my previous post on the opera itself here.

Comments