Her first complete recording was Gioconda in 1952, which followed further performances at the Arena. In all, she performed the role 13 times, including six times at La Scala between December 1952 and February 1953. At the time of those performances, she weighed about 220 lbs. It was after that that she went through her famous transformation. Even at that time her voice was noted as being of an unusual color with a harsh timbre and unevenness between the registers, albeit with abundant volume and extension of range. Right from the beginning her voice invited controversy, but to her fans, she was La Divina.

I have to admit: I am not a fan. However, I do respect the fact that she was the most significant singer of the 20th century. But then again, I am not the biggest fan of Milanov either. And the two couldn’t be at more opposite ends of the spectrum. One is the ultimate “Stimmdiva” while the other is epitomizes the “Kunstdiva.” If you haven’t read your Ethan Mordden, stimm = voice, kunst = art. Actually, I think a singer like Rysanek or Olivero really comes closer to what I think of as a kunst diva. Tebaldi started as a Stimmdiva and ended as a Kunstdiva, but this probably had more to do with the loss of her stimm. Li’l Renata, i.e., Scotto, similarly changed, the difference being that Big R changed as she aged, Scotto because of conviction. Tebaldi thrived because of personality, Scotto in spite of (I’ll explain that later). Of course, it depends on what one values most in opera, but I am a firm believer that Opera is first and foremost about singing. Beautiful singing. Bel Canto. What one does with, how one uses the voice comes next.

Leontyne Price was certainly a Stimmdiva and undoubtedly would have been a great Gioconda, but she couldn’t survive Fanciulla and wisely would not have risked The Voice, therefore no Gioconda – “Suicidio” isn’t even on any of her Prima Donna albums and she pretty much sings the gamut of the soprano territory (other than “Casta diva,” no bel canto either). She knew her voice and that’s why when she sang her final Aïda at the Met 24 years after her first one, she sounded as if she could go on for another 24. All these singers mentioned here had one key thing in common: they all sang with intensity. With one exception, I feel that no singer today sings like that. The exception is Ermonela Jaho. Granted, she does not have the size of voice the others had – and please don’t let her ever do a Gioconda! – but every note she sings has conviction, intensity, and personality along with beauty. That’s what I look for.

“It’s all there for anyone who cares to understand or wishes to know what I was about.”

Mordden posits:

“What is more useful, the sensuality of sound or the intelligent, dynamic, versatile impersonation? … The Stimmdiva’s idea of preparing Gounod’s Marguerite involves learning the music and ordering her outfits. The Kunstdiva reads Goethe.”

Mordden goes on:

“Tebaldi was a highly expressive artist, not an important actress but a finely musical interpreter … Callas was weak in voice and had to make up for it with extraordinary musicianship and commitment.”

And for a final Mordden quote:

“Demented is opera at its greatest, a night when the singers are in voice, in role, in glory.”

I should add that Mordden’s Demented is pretty much a paean to Callas. The most demented night I ever spent at the opera was a Sunday night, Guild benefit Tosca – and by it’s very nature, Tosca is demented – with a scheduled Tebaldi, an unscheduled Corelli, and a returning Gobbi. Unfortunately, I missed the final Callas Tosca as I was off in college, but I have no doubt those were totally demented performances, too. I don’t know about Milanov; I can’t imagine it. A diva who is strictly ‘Stimm’ would be Caballé; however, one of the most demented performances I’ve ever heard was a Trovatore with her, Viorica Cortez, Domingo, and Merrill … interpolated high notes all over the place! As is Tosca and the occasional Trovatore, and hopefully Forza, so too is La Gioconda and our three divas, Milanov, Tebaldi, and Callas, shared those roles, at least to a greater or lesser degree. Now, none of this is not to say that Milanov couldn’t be dramatic (at least in her own way) and Callas has certainly been selling recordings of just her voice for over seven decades.

Oh yes, it seems I’ve gotten off track…

My feeling about the Callas voice, vis-à-vis the art, is that I don’t care for the sound of the voice, but admire what she does with it. So, before I give a few people apoplexy and dig my grave deeper, let me add that if I were to chose the single most moment to illustrate the Callas phenomenon, I find that the soaring phrases following Gioconda giving Laura the poison that conclude the first scene of Act III beginning ‘O mia madre’ and ending ‘per lui … per lui,’ as the best example of her art. Filled with anguish. Beautiful singing? Not necessarily. But the total effect is riveting. Again, it’s all up and down the scale but every note is invested with the sacrifice she is making and the depth of sorrow that it costs her, “O madre mia … il sacrifizio mio.”

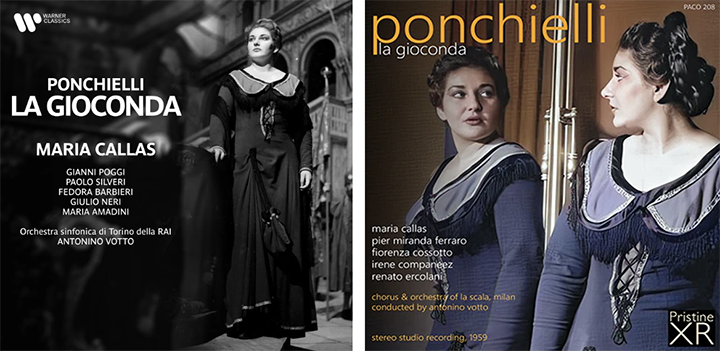

The first to say that Gioconda was her greatest recorded role was the diva herself. She considered this her finest recording, declaring, “It’s all there for anyone who cares to understand or wishes to know what I was about.” She recorded the role twice, first in 1952 following performances at La Scala and again in stereo in 1959. The first difference I find between the two recordings is that in 1952 she was a virtual unknown making her first recording. In 1959, she was the world’s most famous prima donna … and it shows in the performances. It is generally accepted that the later recording is superior certainly in terms of sound and mostly in the cast, but she was in far better voice in the earlier. I gravitate more towards the earlier recording. Never was the Callas voice in better shape and more beautifully used. In the second, I can get past the flapping high notes. But it’s the bottom notes that sound like a buzzer to my ears. Most critics agree that her second recording shows greater depth (and lack of voice). At the earlier point, Callas just about had it all (including fat), but she would not have been The Legend if she had stayed that way.

Callas at La Scala in 1952

Unfortunately, as is often the case in those early recordings, the rest of the cast was not of her caliber and, therefore, the second recording becomes preferable as a statement of the opera. In the first, to put it simply, Gianni Poggi is deplorable. In the second, Piero Cappucilli is the Barnaba on the verge of a big career – one that I never understood. Great voice, absolutely zero personality. No wonder Callas hates this Barnaba so much! Most find Fiorenza Cossotto preferable to Fedora Barbieri in the ’52. In that I also greatly admire the Alvise, Giulio Neri. Neri in Italian means black and that is a perfect description of his bass voice, perfect for the role. Again, I use the word “blowsy” (“blousy”?) — I should attempt to define that. I know I’ve heard others use it but of course can’t find where nor can I find any definition in the vocal musical sense. I think of it as something like an aural equivalent of a puffy shirt or a blouse, a puffed up sound, overly operatic. In Milanov’s sense, it’s a negative; for Neri and Alvise, it is a positive. Antonino Votto, the conductor in both recordings, is excellent and his account especially in 1952 of the ballet and the ensuing concertato — I find is the most exciting on record despite mono sound. To the best of my knowledge, there is no documentation of any of Callas’s early small handful of live performances; it was never part of her natural repertoire any more than Turandot or Brünnhilde were and that she was singing at that time, late ‘40s early ‘50s.

The highlight of any Gioconda performance should be the fourth act that comes after an already very long evening. That last act should be a 30-minute tour-de-force; the first 15 minutes Gioconda is virtually alone on stage. It opens with her only aria, the difficult “Suicidio” followed by a monologue that demands all the emotion a diva can muster up. Of course, this is the high point of Callas’s performance. Well, both of them. No matter what one thinks of her voice, she is amazing. She claimed that she sang it as if it were bel canto – how she integrates the role’s frenzies of love and hatred, rooting Gioconda in the time it was written, between the Bel Canto era and late Verdi, not in that of Tosca and Santuzza. Sorry, I don’t buy that. It is pure verismo from start to finish. And that’s fine.

- 1952 – RAI & EMI: Torino – VOTTO; CALLAS, BARBIERI, Amadini, Poggi, Silveri, Neri

- 1959 – EMI & Pristine: La Scala – VOTTO; CALLAS, COSSOTTO, Companeez, Ferraro, Cappuccilli, Vinco

Critics are divided. A shocking review in The Metropolitan Opera Guide to Recorded Opera by Roland Graeme:

“On this stereo remake of her Gioconda, Callas gives a performance that is at once tremendously exciting and quite painful to listen to. The voice, to put it bluntly, is coming apart at the seams: harsh, almost baritonal chest tones alternate with oddly thin, colorless head tones, loud high notes are strident; and the wobble is omnipresent.”

But he finishes by saying, “even when the voice is in its worst shape, the singing seems as natural a mode of expression as speech.”

There are plenty of critics to counter that and claim not only is it Callas’s best recording, but the opera’s best recording. As a final word on the subject, Francis Robinson, an author and an assistant manager at the Met, gave us an anecdote in which Tebaldi asked him to recommend a recording of La Gioconda in order to help her learn the role. Being fully aware of the rivalry, he diplomatically recommended one of Milanov’s recordings. A few days later, he went to visit Tebaldi only to find her sitting by the speakers, listening intently to Callas’s recording. She then looked up at him and asked, “Why didn’t you tell me Maria’s was the best?”

Next time, we’ll see what all that preparation went towards by looking at Tebaldi’s legacy with Gioconda.

Comments