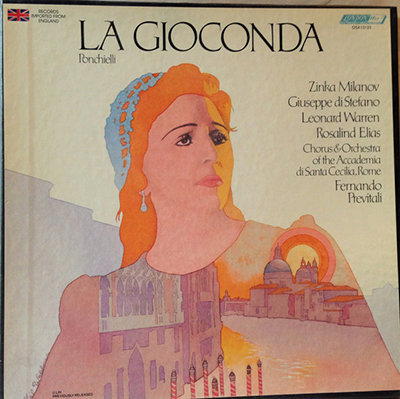

Based on what was written in the first paragraph of the 1958 Time Magazine article “Sir Rudolf Bing’s Nightmare,” it will come as no surprise that the role of La Gioconda is dominated by those “First Ladies of Opera: Maria Callas, Renata Tebaldi, and Zinka Milanov.” All three were ideally suited to the role, but in their own distinct ways. No other Gioconda of the modern era has come close to these three divas. Of the 287 times La Gioconda has been performed with the Met, one-quarter of them were performed by Milanov and Tebaldi. I haven’t forgotten Ponselle, but she was of an earlier time; for the record, she sang 37 performances, Milanov sang 41, Tebaldi 32. I’m not including Ponselle in this survey as, far as I know, she only recorded “Suicidio.”

The first complete studio recording of La Gioconda was also one of the earliest complete recordings on record. It is from 1931 and in amazingly good sound considering its vintage. It is on Naxos with the forces of La Scala under the otherwise unknown Lorenzo Molajoli who leads a very good, authentic performance. Giannina Arangi-Lombardi is the Gioconda, a relatively light voice for the role but still very impressive. My feeling about the whole recording is that if you like voices with a lot of fast vibrato, you will love this. Point of interest: a young Ebe Stignani is the Laura. If there were no other Giocondas to be had, and in 1931 there weren’t, I’m sure it would suffice.

The next available recording is a live performance from the Met on December 30, 1939 with Milanov, Bruna Castagna, Anna Kaskas, Giovanni Martinelli, Carlo Morelli, and Nicola Moscona. The conductor is the reliable and excellent Ettore Panizza. This would indicate it’s time to discuss Milanov.

It’s no use pretending that Zinka Milanov (neé Kunc) was ever an actress, neither vocally nor certainly histrionically. Yet vocally, of those three ‘first’ ladies, Milanov was best equipped. Her pianissimo high B-flat on the “Enzo adorato … comé t’amo” is legendary. Tebaldi’s, on the other hand, became the butt of a backstage anecdote. The stagehands (the stagehands???) used to bet on whether or not she would hit that one note on pitch (I doubt anyone ever won). I think Giocondas fear that B-flat as much as Aïda’s live in terror of the high-C in “O patria mia.” Despite the visual limitations, Zinka’s Gioconda could grip the imagination with a soaring line as if that were the only possible way to sing it and as if the composer had written it specifically with her voice in mind.

Milanov made her Met debut December 17, 1937 in Il trovatore. Two years later, she sang her first Gioconda; it was also her first broadcast. She sang the role at the Met 41 times between 1939 and 1962. Being 33 when she took on the role, the voice was fully mature and it never hurt the voice. However, she also never put pressure – vocally or dramatically – on the voice such as many other Giocondas would do. There’s no denying that from the mid-50s on, the voice was wearing down and was replaced by her many mannerisms; I have to admit that I was not really a fan. I actually saw her twice: in Aïda with an equally stolid Kurt Baum and later in Boccanegra. Granted, this was in the mid-50s and I was something like 9 or 10 years old and the passion for opera hadn’t quite clicked in, but those performances made a lasting impression. Even then the indeterminate pitch and scooping irked me (some would call it “portamento”). Her acting consisted singularly of sweeping her train.

But I came to her late. Listening now to all these Giocondas, the voice is unquestionably opulent, and even in the late performances and the RCA recording she is more impressive than I would have thought. Paul Jackson, in his history of the radio broadcasts, writes of Milanov: “Gioconda looms as the ultimate image of her stage persona and vocal manner. Her resources, both tangible and internal, were perfectly attuned to the role’s outsized musical and theatrical gestures.”

Her legit recording on RCA (later turned over to Decca) was made in 1957, far too late to do her full justice; the same could/should be said of her Enzo, Giuseppe Di Stefano and to a lesser extent the Barnaba, Leonard Warren. One needs to go back to the 1939 for a legendary performance with Bruna Castagna and Giovanni Martinelli or to the 1946 with Risê Stevens, Richard Tucker, and Warren for that. Of her seven (!) Met broadcasts of the role–touching four decades from ’39 to ’61–it’s a shame that as the audio sound improved as the vocal sound declined. Not to say that any performance is embarrassing, just not as good as the previous one. This is a list of the seven broadcasts (all available online) plus the ‘official’ RCA recording and a well-circulated one from New Orleans, followed by my impressions of certain performances. The names that are in caps are for me the standout performances, which is not to say that any of Milanov’s performances were not ‘standout,’ but by comparison these did.

- 12-30-39 – PANIZZA; MILANOV, Castagna, Kaskas, MARTINELLI, MORELLI, MOSCONA

- 3-16-46 – Cooper; MILANOV, STEVENS, Harshaw, Tucker, Warren, Vaghi

- 1-3-53 – Cleva; MILANOV, Barbieri, Madeira, Baum, Warren, SIEPI

- 3-2-55 – Cleva; Milanov, Rankin, WARFIELD, BAUM, WARREN, Tozzi

- 4-20-57 – Cleva; Milanov, Rankin, Amparan, Poggi, Warren, Siepi

- 1-10-59 – Cleva; Milanov, Rankin, Amparan, TUCKER, MERRILL, Siepi

- 4-1-61 – Schick; Milanov, Rankin, DUNN, Baum, Merrill, Wilderman

- 1957 – RCA – Previtali; Milanov, Elias, Amparan, Di Stefano, Warren, Clabassi

- 10-8-60 – New Orleans – Cellini; Milanov, Kramarich, McMurray, Gismondo, Bardelli, Wilderman

- 1939

The 1939 on the whole would be the best if the sound were better though it’s not bad considering the date. For me, despite the murk, Ettore Panizza was the best conductor of them all – well, that really just means up against Fausto Cleva, perhaps it was just good to hear someone else as Cleva conducts most of Tebaldi’s Gioconda performances as well. Panizza, whom one critic referred to as a “Toscanini clone,” actually makes the furlana dance fun and enjoyable. The draw here should be Martinelli but at age 54, this is not the voice of a young man and he is a drawback instead. That becomes immediately noticeable in the next performance when compared to the debuting Richard Tucker. But still he sings with authority and knows how the music should go. What I particularly liked about Carlo Morelli and Nicola Moscona is that they were the most dramatic, think evil, of any of the Barnabas or Alvises.

- 1946

The 1946 performance is also one of those considered “legendary” undoubtedly because we were hearing Tucker and Leonard Warren for the first time, but it was Risë Stevens who makes a considerable impact as she turns out to be the most theatrical Laura, even though she might not have the voice of some others. For me, the best all-round of the seven broadcasts is the following one from 1953. Milanov peaks and Cesare Siepi makes one immediately sit up with his resplendent bass, even though he’s not quite as evil as Moscona. Warren is magnificent but his best is the following broadcast in 1955.

- 1955

The same with Kurt Baum. He really surprised me. Margaret Juntwait on the Sirius rebroadcast charitably described his voice as “robust.” That’s an understatement! If ever a tenor lacked subtlety, it was Baum. “Baum” in German means tree and that’s a good representation of him. Regardless, in the ’55 performance his “Cielo” is absolutely thrilling, even if it lacks the slightest bit of style or artistry. Likewise, he and Zinka soar spectacularly over the ensemble in the concertato. Baum is not the deterrent one would have expected. Also in that performance Sandra Warfield is a particularly riveting Cieca and comes closest to being a true contralto. Side note: Warfield’s husband sings a “singer” in the performance; he later went on to become the leading Otello: James McCracken.

- 1957

The standout of the 1957 performance for all the wrong reasons is the bleating of Gianni Poggi who blighted not only Callas’s 1952 recording, but also one of Leyla Gencer‘s recorded performances. Warren’s mannerisms were also starting to set in. Jackson again questions, what “compels him to shudder” for dramatic effect? My word was quiver, which is different from exaggerated vibrato. It ultimately turned me away from his performances. By this time, Zinka was starting to zink. The tone was becoming more blowsy, the pitch could be iffy, more scooping in and out or notes, the notes not held as long … I really missed her long-held high Cs soaring out in the final act trio.

- 1959

Regardless, at least on paper, the cast for the 1959 performance was really exciting. Robert Merrill was singing Barnaba for the first time. Not only the glorious sound of his voice astonishing, but the malevolence in it was especially surprising as I always found him a dramatic void in the Tebaldi/Decca recording … what happened? I wasn’t that thrilled with Tucker’s Enzo in its initial ’46 hearing, but (hardly surprising) he had much improved by 1959 and by the end of “Cielo e mar,” he was in top form. He also had his mannerisms that became more and more pronounced. Tebaldi called him the most Italianate of tenors with his stylistic affection for sobs and explosive diction. She also called him “Mr. Terrific” because whenever asked how he was his reply was, “Terrific!” In 1970, Mr. Bing who always referred to Tucker as the American Caruso, celebrated his 25 years at the Met with a gala that included the first act of Traviata with Dame Joan Sutherland, the third act of Aïda with Leontyne Price, and of course the second act of Gioconda with his favorite, Renata Tebaldi. For Milanov’s final performance, which was at the end of an extremely long gala for the final performance of the old Met, she and Tucker sang the final Chenier duet.

Here’s a 25-minute bit of fun…

Next, we’ll take a look at Callas in a role that was absolutely fundamental to her artistic development.

Comments