By no means had he been idle, as he had been coaxed into politics and served in the Parliament of the newly unified Italy. Best of all though, he preferred staying home and being a gentleman farmer at Sant’Agata less than two miles from the village of Le Roncole, where he was born in 1813. In December of 1860, he had a letter from Russia from a close friend, the tenor Enrico Tamberlik. Tamberlik was Italy’s leading tenore robusto. According to contemporary accounts of his singing, Tamberlik possessed a big, incisive voice with a pervasive vibrato and ringing top notes—including a potent top C-sharp delivered in full chest voice that he used to great effect (and with the composer’s blessing) as Manrico in Il trovatore. He was an exceptionally exciting interpreter of dramatic roles, and as the most celebrated Italian tenor of the middle 19th century, he was especially known for such parts as Jean in Le prophète, Arnoldo in Guglielmo Tell, (Rossini‘s) Otello, Pollione, Arturo, Ernani, Robert le Diable, Faust, Don Ottavio, Florestan, Poliuto and Benvenuto Cellini. In addition to Alvaro in Forza, Verdi certainly had his voice in mind when he wrote Otello.

Tamberlik at the time had been a guest artist at the imperial theatre in St. Petersburg, the Bolshoi Kamenny Theatre. The theatre was torn down in 1886, deemed unsafe, and the competing Mariinsky became the imperial theatre. On behalf of the Kamenny, Tamberlik wrote to Verdi that as the theatre had such an excellent roster of Italian artists and that the composer’s works were so popular in Russia, he should write an opera for St. Petersburg. The prospects stirred Verdi’s creative interests that by now were becoming restless. The first work proposed was Ruy Blas by Victor Hugo but the work proved to be too politically controversial for the Tsar and Verdi finally settled on Forza, a work that had tempted him ten years previously. The contracts were signed by summer for a première in early 1862, and Verdi set to work composing quickly enough for he and his wife, the famous, retired singer Giuseppina Strepponi, to set off for St. Petersburg in November. The long trip via Turin, Paris, Berlin, and Warsaw, took about three weeks. While Verdi composed, Giuseppina packed: rice, noodles, macaroni, cheese, salami – enough for them and the two servants they were bringing: 100 bottles of ordinary Bordeaux, 20 bottles of vintage Bordeaux, 20 bottles of champagne. To a friend, she wrote, “The noodles and macaroni will have to be well cooked to keep him in a good humor in the midst of all that ice! … And I plan to let him be right in everything from the middle of October to January. I know that while he is composing and rehearsing the opera, it isn’t the moment to persuade him that he might be wrong even once.”

Giuseppina Strepponi

When Verdi finally arrived in St. Petersburg ready to start rehearsals, he was met with the news that his prima donna, Emma La Grua, was ill. The “curse” of Forza had started. After several weeks, she showed no signs of improving and there was no replacement. The role of Leonora was just as hard to fill then as it is today. The Verdis spent their time sightseeing including a trip to Moscow and were honored and lavishly feted everywhere. They thoroughly enjoyed themselves. Finally, it was agreed to delay the première until the fall. The Verdis returned to Italy. In May, Verdi went to London where he had been commissioned to write a cantata for the International Exhibition, the type of project that he did not enjoy doing. The piece, with text by Arrigo Boito, was composed for Tamberlik, but in a dispute with Covent Garden, the theatre refused to release him and he was finally replaced with the soprano Thérèse Tietjens as the soloist. The Inno della Nazioni (The Hymn to the Nations) finally received its première on May 24th 1862. The work is a bit on the tacky side but loads of fun. In the 20th century, it was often used for propaganda purposes. Arturo Toscanini conducted it in 1915 shortly after Italy entered World War I. He again famously led a performance in 1943 in which he added the Soviet “Internationale” and “The Star Spangled Banner” and which was recorded with Jan Peerce and the NBC Symphony. Coincidentally, it was preceded by the overture to Forza.

Having made a few changes in the score, Verdi returned to St. Petersburg in September and La Forza del Destino finally had its première on November 10, 1862. Caroline Barbot replaced La Grua. The performances were a great, albeit qualified, success. Tsar Alexander II and his court attended, applauding and cheering. Typically, Verdi was the chief critic to find fault. Leaving Russia in December and spending Christmas and New Year in Paris, Verdi made some quick revisions and headed to Madrid for a February première with the Duke of Rivas, the play’s author, in attendance. At the same time, the opera premièred in Rome without Verdi’s supervision. The opera subsequently travelled to New York and Vienna (1865), Buenos Aires (1866) and London (1867). For the time being, Verdi would not allow any further performances in Italy, in particular not at La Scala with which he had been on the outs for 24 years since the première of Giovanna d’Arco in 1845; he had recently cited the inferior quality of performance there.

Clearly Verdi did not like the cold. Wrapped in furs, he is seated in the front of the sled.

THE REVISED VERSION(S)

Over the next few years, Verdi tinkered with ideas for revising Forza, but was stymied by how to resolve the ending without so much violence. Meanwhile, he made major revisions to his 1847 opera, Macbeth, and composed what was to be his most ambitious albeit frustrating work, Don Carlos, for the Paris Opéra which opened March 11, 1867. In 1868, while Verdi was in Milan promoting the idea of a requiem mass in memory of Rossini to be composed by Italy’s leading composers, he was approached by Giulio Ricordi, the third generation of the leading house of music publishers, Casa Ricordi. Ricordi’s idea was to publish a revised version of Forza to open at La Scala. Giulio, along with Clara Maffei, Verdi’s close friend, put considerable pressure on Verdi’s patriotism, explaining that La Scala was in serious trouble and needed him. Clara Maffei, the estranged wife of Andrea Maffei, the librettist of Verdi’s I masnadieri and the revised Macbeth, was a woman of letters, strong supporter of the Risorgimento (the movement for the unification and independence of Italy), and the renowned hostess of Milan’s salon society. The Austrians had richly subsidized the theatre and that now with the reunification they were out of power; the new Italian government was poor and could not support the annual subsidy.

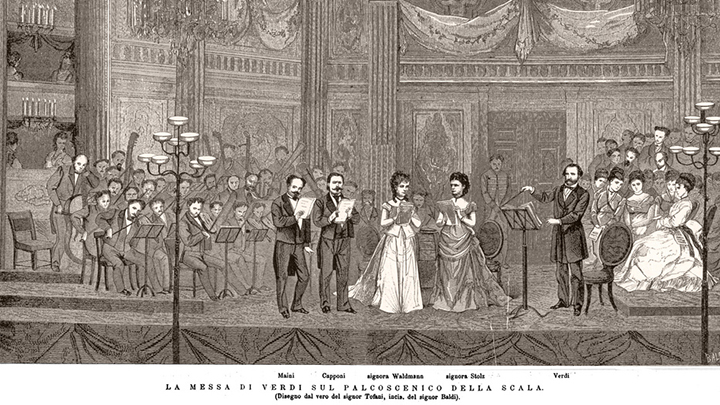

Verdi made enormous demands and outrageous conditions for his return all of which were met. One of these conditions was for him to assess the current quality of the orchestra, chorus, and other performance standards of Scala. As he wanted his presence to remain unknown in doing such, he timed a journey from Genoa to Milan that he knew to be eight hours and 10 minutes so that he would arrive at the theatre exactly after the second act had begun. The opera being performed was his Don Carlo, newly translated from the French. The Elisabetta was Teresa Stolz and in all likelihood this was his first time seeing her. The Bohemian Stolz became the Verdian dramatic soprano par excellence. From this point forward, Verdi composed his soprano roles with her voice in mind. She was the Leonora for the first performances of the revised Forza, she created the role of Aïda at La Scala which Verdi thought of as the real première, and she was the first to sing the soprano part in his Requiem. Stolz became a very large part of Verdi’s life, both Verdi’s and Giuseppina’s – how much is open to speculation.

The new version of Forza was premiered at La Scala, Milan, on 27 February 1869, and has become the “standard” performing version. Piave, who had been Verdi’s close friend and favorite librettist since Ernani in 1845, was no longer able to rework his libretto as he suffered a stroke late in 1868 and remained an invalid, paralyzed and unable to speak until his death in 1876. The composer helped support his wife and daughter and paid for the funeral. The revisions and additions to Forza were made by Antonio Ghislanzoni, who was to become the librettist for Aïda. Verdi fiddled over changes for seven years.

An engraving of the first performance of the with Requiem Teresa Stolz

Verdi was unhappy as the score stood. What chiefly worried him was the gloomy and melodramatic dénouement with its three violent deaths. “Friends and enemies” alike had been asked for suggestions for a new ending. Verdi almost considered approaching Rivas himself on the subject. It was even suggested that Verdi give it a happy ending: “Fate cannot accommodate the two families after so much fracas. The brother has to take his revenge – and remember, he is a Spaniard – for the death of his father. He can never, repeat, never acquiesce to a marriage.” (From a letter Verdi wrote to Escudier, the French publisher.) In the end, Verdi realized the ending for himself. The three primary characters had gone too far for ordinary reconciliation and the only alternative was to reverse the tormented Alvaro’s blasphemy and accept his suffering as the will of God. The final duel between Alvaro and Carlo, the latter’s death, and his stabbing of Leonora now take place off-stage. Supposedly. It now seems to be the modern trend to bring the duel, Carlo’s death, and the stabbing back on stage, at least in the John Dexter revival at the Met and the recent Milan and Munich productions. It’s probably preferable and not so easily perceived as avoiding an issue though it certainly means the baritone has to lie still for some ten minutes. Either way is awkward, but probably not as awkward as it is offstage. More awkward was Alvaro’s original suicide by damning himself to hell and jumping into a ravine while calling down a dreadful curse on mankind. Personally, I’d rather go for that ending … but that would mean sacrificing the ethereal “new” trio. The resonance of the second version of the finale, its reference – and reverence – to musical themes earlier in the opera, tells us that Alvaro’s redemption is the fulfillment of a process that began with his Act III aria.

Once the composer was satisfied with the new ending, he made many changes elsewhere; small ones throughout the whole work to give more focus to the musical flow and all of which are for the better. There were, however, two very large and obvious changes besides the finale: the addition of a full overture and the substantial rearrangement of the scenes of Act III. Verdi took the original prelude as his starting point with its slashing chords of fate, and then he leads us in another direction with the tunes becoming a potpourri of the opera’s greatest hits. It could be argued that the original prelude brings us more quickly into the conflicts awaiting us once the curtain is up, but the new overture is probably Verdi’s best and most popular. For years, the full overture was played at the Met between the first and second acts with the seeming intention of covering the set change. This never worked for at least two reasons: the opening of Act I following the overture in itself is rather weak and, second, the prelude or the full overture is clearly an introduction, not an intermezzo. In my imagined production, my solution would be to play the original prelude that dissolves into the first act. And then following that act and preceding the next, continue with the new overture from the point that the prelude breaks off thus denoting the passage of time … the best of both worlds.

Act III presents more problems. It was Verdi’s idea to give more focus to the central plot by bringing the very different strands of the three-part act together and keeping the main dramatic line, Carlos-Alvaro, as one unit of the drama moving from their initial meeting, through their friendship, their discovery of their true identities, to the duel, and Alvaro’s decision to seek inner peace and consolation by taking holy vows. Verdi moved the genre scene of the army camp to conclude the act with the dazzling “Rataplan.” Personally, I don’t think this was an improvement, and nor do a lot of others. In the re-directed revival of Forza at the Met in 1975 in which the opera was being given complete for the first time, surprisingly it was not the conductor James Levine but the director John Dexter’s idea to revert to the original order (though of course it had to be with Levine’s blessing). This was hardly an original idea of Dexter’s as it was apparently common practice in Europe. Arguably, the large choral “Rataplan” is a stronger ending musically, but dramatically the duel leading to Alvaro’s rousing and soaring phrase is far more thrilling. Most importantly, it brings the central plot to the forefront that leaves the audience hanging through intermission for the final act.

What has been chiefly lost in the revision, no matter which way it is presented, is Alvaro’s forceful aria “Miserere mei Deus” which is a real test for the tenor and was obviously written to allow Tamberlik to show off his brilliance. The aria is “a portrait of the hero at full height” and it almost acts as a cabaletta to Alvaro’s act-opening aria, “Oh, tu che in seno agli angeli,” forming an arc to the entire act. The aria in the revision has been reduced to a single phrase, although a very exciting one. It would be wonderful if the full aria could be re-interpolated into a present performance, but the aria is almost impossibly difficult. If anyone should have been able to do it (not counting for style), it should have been Gegam Grigorian in the live performance from the Kirov of the original version, but he falls apart with it. Placido Domingo included it in his 4-disc survey of all the Verdi arias. Furthermore, the act is difficult enough containing three tenor-baritone duets and difficult, extended arias for both. Structurally, the original order breaks them up as it breaks up a genre scene with an aria for Melitone at the end of the act with the same for the beginning of the next act. Who are we to question the Master, but I will never understand Verdi’s reasoning of this particular revision. Reading the synopsis currently on the Met’s website for the new production, the act will end with the “Rataplan” – what ominously looks like one of some rather predictable mistakes.

In 1882, there was a third version, La Force du Destin, obviously done for the Paris Opèra. I know almost nothing about it except what I read in Budden. Apparently, there is no pistol shot … something about Curra blowing the candles out, there’s sword fighting in the dark and the Marchese gets wounded … whatever. There is also a new intermezzo in Act IV that gathers up the threads of the story of Leonora, who has been missing for a very long act and a half and at which point she has become no more than a distant memory for both Alvaro and the audience. The intermezzo serves as a dream sequence, a montage of past and future events and I’d certainly be curious to hear it. According to Budden, the excisions that Verdi made in this French version is that too much happens too quickly, too soon. It became a problem of proportion, the same problem that Verdi faced in revising Don Carlos.

Critical editions of all versions of the opera were prepared by musicologist Philip Gossett. In 2005, the critical edition of the 1869 version was first performed by the San Francisco Opera whose program book included an essay by Gossett on the evolution of the various versions: “La forza del destino: Three States of One Opera.” In July 2008, Caramoor gave a concert performance of the critical edition of the 1862 version plus never-performed vocal pieces from the 1861 version, that being as what Verdi composed originally before any rehearsals and the break of nearly a year before the première. This makes four versions.

On Friday, we’ll be discussing the characters onto whom Verdi mapped these versions.

To learn more about the opera, take a look at the previous installment in my Forza series which covers Verdi’s influences.

Comments