Among its rich treasures, it includes arias and duets that are some of the most inspired of the entire Verdi output. I discovered the opera early on in my teenage infatuation with opera in general and Renata Tebaldi in particular. Leonora’s great aria, “Pace, pace, mio Dio” was the concluding offering on a disc of my father’s that was simply entitled, “Renata Tebaldi, Operatic Arias” that led me further into the full opera.

Following my multi-part essay Thoughts on Don Carlo(s), published here on parterre (Parts 1, 2, and 3) and which critic Christopher Corwin called “essential,” it was a tough decision as to what operatic project I wanted to tackle next. I’d run out of composers I was willing or felt remotely qualified to write about. What I really wanted to do was to write about an opera as complex and rich in actual history as Don Carlos; unfortunately, there isn’t any other though the Ring and maybe some of the other Wagner operas offer other insights, but I’d already done them at least as far as recordings go. I go back though to the composers and operas I have written about and the very first set, those of Verdi, were simply one or two sentences about each opera, the primary focus being on the recordings. So the ultimate decision was easy; however, having “thoughts” on Forza wasn’t going to be.

Urban Sprawl

Verdi called his Forza an opera of ideas (“intenzioni”), ‘intentions’ or, if you will, ‘thoughts.’ The thought that comes first to most people is that Forza is ‘sprawling,’ a thought of which Verdi was well aware. Verdi in adapting Don Alvaro o Le Fuerza de Sino wanted to create an epic in which a tale of love and fate would be juxtaposed with scenes of everyday life, in this case with a background of war.

From a dramatic point of view, yes, Forza is sprawling, especially by Verdian standards – a muddled, episodic drama made up of a series of scenes, some of which appear so crowded with secondary characters and attention-diverting local color that it is all too easy to lose the thread of the main story line. As if the structure of Forza wasn’t confusing enough, Verdi and Piave took a scene from Friedrich Schiller’s Wallensteins Lager to add even more to the riffraff of characters. In this respect, though written a decade in the future, Boris Godunov is similarly laid out and would not have been imagined without the influence of Forza. Regardless, Forza achieves its distinction and character from the complex libretto Piave fashioned from the lengthy Spanish play by Ángel de Saavedra, the Third Duke of Rivas. Francesco Maria Piave (1810-1876) was not only a close friend of Verdi, but had written ten librettos for the maestro starting with Ernani and included Macbeth, Rigoletto, and La traviata.

One can wonder why Verdi adopted the subtitle of the play rather than the name of the protagonist for the title of his opera. I read somewhere that Forza is the only Verdi opera whose title uses a psychological emotion instead of the name of the protagonist or a very specific event in that protagonist’s life. That’s not quite right as certainly “traviata” (ie. “the lost one”) is a psychological state, but I see the point. In Forza, it is what are referred to as the genre scenes, the scenes with local color-the peasants, the monks, the soldiers, the hangers- which transform Forza from a depressing drama of three doomed characters caught up in a blood-feud into something far richer and more human. Characters such as Preziosilla, Melitone, and Trabucco allow us periods of relaxation from tensions generated by Carlo’s pursuit just as the noble Padre Guardiano who offers shelter enables Verdi further to enrich the score with music that is both dignified and serene. This is exemplified in the second act with its two very contrasting scenes: the inn and tavern at Hornachuelos with its hustle and bustle, its transience, a place where people come and go, as opposed to the monastery, a place where people end their journey. From the moment the pistol accidentally goes off in the first act, Leonora’s and Alvaro’s lives are controlled by fate. Of the many strange coincidences in opera, none seems more far-fetched than that loose-triggered gun. However, consider all the accidental shootings that we read about in today’s newspapers (think of that shooting on the set of Rust). Leonora and Alvaro have no wills of their own; their lives are controlled by unintentional coincidence. Both, though at different times, enter the monastery renouncing will. They are safe. Indeed, Leonora states when she arrives at the monastery, “Son giunta” – I’ve arrived, I’m safe here. The monastery provides a kind of anchor for these characters adrift, a place for help and guidance. The opera is thus not about individual characters, but how these characters react to the workings of destiny. The central character is fate and how it affects all segments of society, from the highest to the lowest.

Of all the operas in the standard repertoire, Don Carlos and La forza del destino are the ones that are most butchered: sliced up, rearranged, parts thrown on the scrapheap, entire scenes tossed out. The minor characters are never sure what scene they’ll be in if they haven’t been cast aside altogether. Arias and duets come and go. Even the vocal scores sometimes omit whole scenes. And the fault is Verdi’s. His ambitions exceeded even his very capable abilities, and he couldn’t seem to get it right. In his age of Romanticism, Verdi wanted to create in Forza a panorama of humanity juxtaposing the scenes of everyday life with the story of a brother’s obsessive search for revenge against his sister and her lover. However, those scenes of everyday life don’t have nearly the force of the passionate scenes, and so from Verdi’s time to the present, alternatives have been sought to iron out the rough edges. Forza’s many scenes are more like isolated progress reports than moving parts of cause-and-effect plot construction. It is hard to find a point of focus in the opera. Leonora is the main focus at the beginning and then it turns to Alvaro only to return to Leonora in the final scene. These main characters are forever in search of (or attempting to avoid) each other. One coincidence follows another. The minor characters of Preziosilla the warmonger, Fra Melitone the grouchy monk, Trabuco a muleteer in one scene and a peddler in the other, all find themselves at the same time and place as the brother and the lover in another country some 1500 miles from where they started only to return. Worse, when they return several years later, the brother and lover both find themselves in the same monastery as the sister. Add to the confusion that they are constantly in disguise and changing their names: the baritone when we officially meet him, calls himself Pereda, a student, then Don Felix de Bornos, and then to his real self, Don Carlo di Vargas; the tenor we know as Don Alvaro becomes Don Federico Herreros then Fra Raffaele. Even Leonora disguises herself as a boy.

The Influence of Shakespeare

Just as Shakespeare moves his characters such as Hal, Falstaff, Lear, etc. all over England and elsewhere, Verdi in Forza moves them around Spain and then Italy (though as I study the libretto, there is extremely little in it that actually refers to the third act taking place in another country) and back to Spain. Verdi as well ignores the concept of unity of time; according to the opera’s production book prepared by Piave, the librettist: “About 18 months pass between the first and second acts, several years between the second and third, more than five years between the third and fourth. In all, the time spans about a decade. As a result, unity of action is wholly broken. Between acts, a great deal happens.”

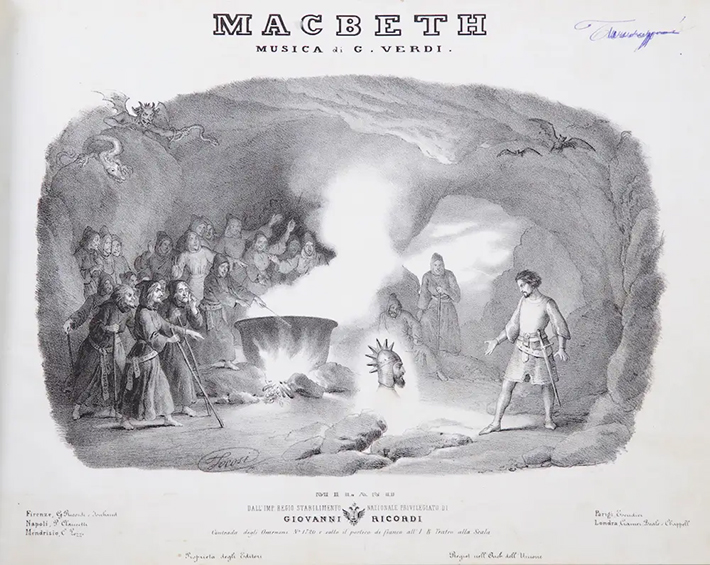

There is no question of Verdi’s love for Shakespeare. For much of his life, Verdi kept the first Italian translation (1838) done by Carlo Rusconi of Shakespeare’s complete plays at his bedside. Being fluent in neither English nor German, he was forced to read Shakespeare in Italian or French translations. Busseto had an excellent small library and Verdi used it. He did not leave the tiny provincial town until he was 19 when he went to Milan to study. Verdi’s experience with Shakespeare, therefore, was literary, not theatrical. He read the plays, but seldom saw them performed. He saw his first Shakespearean play Macbeth performed in London in July of 1847 in a language he did not understand. He was 33 at the time. Verdi staged his first version of the opera Macbeth in Florence three months earlier in March of 1847 without ever having seen the play performed. The first performance of the play in Italy was not until 1858. Protesting a critic’s judgment regarding Macbeth that said the composer neither understood nor felt Shakespeare, Verdi replied: “No, by God, no! He is one of my favorite poets. I have had him in my hands from earliest youth, and I read and reread him continually.” He fashioned three of his greatest operas, Macbeth, Otello, and Falstaff after the Bard and toyed unsuccessfully for many years with Lear. But structurally, what might be considered his most Shakespearean opera is La forza del destino. Instinctively as well in fact, Verdi knew Forza was Shakespearean. In a letter to his close friend Clarina Maffei regarding the opera, he wrote that he was trying “to invent reality” in Shakespearean style rather than merely “to copy” a reality already invented by Shakespeare. In other words, to write an opera that seemed like Shakespeare but wasn’t.

There were many aspects of Shakespeare that appealed to Verdi: the poetry, the themes, the characters. He liked the variety of dramatic situations within a single play. One way to achieve Shakespearean variety in a single opera for him was to mix the comic and tragic genres. Verdi had done this to some extent and with great success in Un Ballo in Maschera the opera immediately preceding Forza. In his definitive books on the operas of Verdi, Julian Budden spends considerable time in the chapter on Forza discussing in particular the German philosophers of the 19th century with whom Verdi would have been familiar and their thoughts on Drama as it related to the historical definitions of Drama. According to Aristotle in his Poetics discussing Sophoclean tragedy, he took as a rule of good structure a unity, or coherence, of action, time, and place; each step in the drama should develop out of the last and bring the ultimate catastrophe one step closer. For Schlegel in the 19th century, Shakespeare, with his mixing of genres and disregard of the unities, fashioned Romantic drama which embraces at once the whole of the checkered drama of life with all its circumstances. In Un ballo in maschera, Verdi observed the rules for unity of action and of time, and only slightly modified of place. In Forza he would be far more daring in mixing the genres to a greater extent and abandoning Aristotelian dramatic precepts altogether. In a letter to Salvatore Cammarano, the librettist of La battaglia di Legnano, Luisa Miller, and Il trovatore, Verdi expressed his desire to insert a scene into Forza such as the one from Schiller’s Wallensteins Lager, that contained the kind of variety he sought: a true picture of a military camp – soldiers, camp followers, nomads, fortune tellers, even a monk, a chance for a little dance for “gypsies.” Shakespeare made his secondary characters reflections of his principal characters. Verdi used the comic and serious to contrast rather than to reflect the characters.

About 18 years later near the end of his life, for his final two operas Verdi returned to Shakespeare. After his experience with Forza and the failure in his own eyes and those of others, he came with a wary eye. He rejected just what Schlegel declared to be the essence of Shakespeare and of Romantic Drama: the mixing of genres and disregarding of the unities. What Verdi saw as “the whole checkered drama of life with all its circumstances” proved to be a failure. It was the Shakespearean structure that so fascinated him that he changed and he adapted two of the plays that were most atypical. Othello was the least Shakespearean in structure of the tragedies. Only once in Cyprus is the unity of place fixed; the span of time becomes 24 hours or thereabouts: evening, morning, afternoon, and evening; the time is unbroken and inexorable. The Merry Wives of Windsor in its structure is the most atypical of all Shakespeare’s plays; it is the only one to observe the unities of time and action, and it goes farther than most in observing the unity of place, never departing from Windsor and its environs. Whether or not it was the structure of Forza that had failed him, Verdi in returning in his old age to Shakespeare looked not for what he loved best in him or was most typical, but for what was now most useful. It proved to be paradoxically the plays of his favorite poet that were the least typical of his favorite poet’s style.

The Cursed Opera

Among the many unfounded backstage legends and superstitions, there’s the one that Forza brings bad luck. Verdi’s opera is for singers what Shakespeare’s Macbeth is for actors, a bad-luck piece whose names must never be mentioned; “the Scottish opera” or “the Scottish play” is sufficient. How and why this started, who knows? The story of Forza is an emotional melodrama about the events caused by the curse put on Leonora by her dying father. Perhaps that curse has spread further, first striking when the intended Leonora got sick at the first rehearsals in St. Petersburg and the première had to be cancelled for almost a year. Whoever wants to believe in such stories better stay away from the opera, which has often been referred to as “The Power of Fate” to avoid calling it with the real title, The Force of Destiny. The idea that the opera is cursed is no doubt due more to cultural superstition than actual events. The one event connected with Forza that leads one to wonder if there is indeed a curse occurred on the night of March 4, 1960 at the Met, in the first performance of the season La Forza del Destino with Renata Tebaldi and tenor Richard Tucker. Leonard Warren, one of the greatest Verdi baritones of all time, was about to launch into the cabaletta to Don Carlo’s aria which begins “Morir, tremenda cosa” (“to die, a momentous thing”). While Rudolf Bing reports that Warren simply went silent and fell face-forward to the floor, others state that he started coughing and gasping, and that he cried out “Help me, help me!” before falling to the floor and remaining motionless. A few minutes later he was pronounced dead of a massive cerebral hemorrhage, and the rest of the performance was canceled. Warren was only 48.

Such events and the “curse” have prompted singers and others to do strange things to fend off possible bad luck. The extraordinary Italian tenor Franco Corelli was rumored to have held on to his crotch during some of his performances of the opera as ‘protection.’ The very superstitious Luciano Pavarotti never sang the tenor role in this opera, despite singing nearly every other role in the Italian repertoire. In his book The King and I on the great superstar tenor, Herbert Breslin, Pavarotti’s long-time manager wrote:

“I thought I had finally talked Luciano into something I had wanted for years. I thought I had finally convinced him to sing Forza. He had, after all, already recorded most of the big excepts from it. And his voice was so perfect for Verdi roles. He agreed. We had the contracts for a big Met performance. But there was that superstition always at the back of his mind: Forza is a bad-luck opera. And superstition won. He called me and said, ‘I can’t do it. I just can’t do.’ Joe Volpe’s response was, ‘What made me consider, or Jimmy [Levine] think, that he’d ever do it, given that he couldn’t even say the name of the opera. I don’t know.’ The Met had to switch to Ballo in Maschera instead.”

While musically brilliant, I don’t think ‘seeing’ Forza enhances one’s perception of the opera as it does Don Carlos. People complain that the opera is too long and then further complain that the comic and serious scenes also do not cohere into any kind of unity; the coincidences, the confusion exhaust the audience. This is half the reason the opera has always been in and out of fashion and the repertoire; the other half, of course, being the extreme difficulty of finding the singers for the demanding principal roles.

In next week’s installment of this four-part series, we’ll move on to discussing the opera’s premiere as well as the various revisions it underwent after.

Comments