For me, what would make it satisfactory is for a recording or performance to be done en français, in the un-cut, pre-Paris premiere version as it was originally composed in 1866, and with brilliant singers.

There are actually two recordings that meet the first two criteria but a long way from the third. Even given those premises, there will be those that claim it sounds better in the Italian translation no matter how poor that translation is. Then, besides the cuts, there are the revisions Verdi made that might or might not be better. It’s a lot to consider.

I am going to assume that anyone reading this is familiar with both the plot and the music and, if not, then synopses, libretti, recordings, and even the revised score can easily be found online.

I’m a strong believer in opera is first and foremost about singing and the voice and the music. For me, action, words, plot usually come after, yet I feel Don Carlos is first and foremost about those latter options. The opera scales heights unheard of in Italian opera.

With the obvious exception of Wagner’s Ring, there is no opera that is more endlessly fascinating – on many levels. Certainly Don Carlos is Verdi’s richest, most complex, and ambitious work as well as his longest. The composer was basically at the height of his powers even though Aïda, the Requiem, Otello, and Falstaff were still to come.

Yet, despite its magnificent music and what many consider to be his greatest opera, Don Carlos is not a “popular” opera and it remains his most problematic. It’s easy to see why and it’s not because it lacks “hit” tunes or the maze of the many versions. At the forefront of problems is the very equivocal, enigmatic, weak figure of the title character and at the other end is what could be the most unsatisfying ending of any opera.

No matter which version is used or how one interprets the libretto and stage directions, I’ve yet to come across a staging that doesn’t leave the audience scratching its collective head. This is a problem of which Verdi, his librettists, and Schiller, on whose play the opera is primarily based, were well aware.

As I considered how to approach this paradox, I did considerable research and read everything I could get my hands on, not only on the web, but the various books and articles and recordings. Not surprisingly, I found articles that pretty much echoed my own thoughts and I’ve wondered why I’m bothering to write about it at all; a lot of these writings border on the incomprehensible.

The “bible” on the subject, Julian Budden’s The Operas of Verdi seems (un)clearly to be written for either musicians or musicologists who speak fluent Italian, French, and German and can sight-read music or who have a lot of time on their hands and can follow with a recording the many musical examples offered; many of those examples have no recording, at least one that I can find.

That being said, I approach this as my personal thoughts on the opera.

At the center of these thoughts is how the character of Don Carlos should be played. Most of us want at the center of a heroic epic a hero, romantic and ambitious, and, in the case of an opera, with great music to sing. Verdi’s and Schiller’s hero might aspire to those qualities but clearly doesn’t have them.

In the case of the opera, the vocal limitations of the tenor, Jean Morère, who was contracted by the Paris Opèra to create the part, no doubt helped to shape the role. For the most part, Carlos’s music is relatively unchallenging; his one aria is hardly Verdi’s most inspired melody, while the music that surrounds Carlos’s is some of Verdi’s most inspired.

In fact, Elisabetta’s great aria, “Tu che la vanità,” one of the greatest in the literature, was earmarked for Carlos’s “eleven o’clock” number and many of the words Elisabetta sings could have been sung by Carlos. Undoubtedly, Verdi was aware of Carlos’s real history and surely must have been at odds to portray him accurately versus what would work theatrically.

In all probability, Verdi was aware of Carlos’s real history and surely must have been at odds to portray him accurately versus what would work theatrically. Before continuing, a look at the actual historical characters and events and how they compare to those in the opera or Schiller’s drama would be in order.

I’d often thought that perhaps the stories about Carlos were exaggerated and that Philip for whatever reasons wanted him out of the way, creating the rumors of Carlos being mentally unstable. The actual facts suggest otherwise.

Don Carlos, Prince of Asturias, was born July 8, 1545, the eldest son and heir-apparent of Philip II, King of Spain, and grandson of the Holy Roman Emperor, Carlos V, who had abdicated. His mother, Maria of Portugal, died four days after giving birth to him.

Carlos had only four great-grandparents instead of the usual eight, and his great-great-grandparents numbered six instead of 16; his maternal grandmother and his paternal grandfather were siblings, while his maternal grandfather and his paternal grandmother were also siblings; his two great-grandmothers were sisters. Try doing a family tree for that!

It is true that Carlos and Elisabeth of Valois, the eldest daughter of King Henry II of France were betrothed – when they were both 14. For political reasons she instead married Philip. In Spain, she was called Isabel (there are places in the opera that Carlos confusingly calls her that).

Three other brides were also suggested for Carlos: Mary, Queen of Scots (think Maria Stuarda), Marguerite de Valois (the same as from Les Huguenots), and Anna of Austria who later became Philip’s fourth wife … such operatic inspiration!

In 1562, Carlos fell (?) down a flight of stairs causing serious head(?) injuries and resulting in wild, sadistic, and unpredictable behavior; he supposedly contemplated murdering his father. Before fleeing to Flanders (mostly what we know today as Belgium and the Netherlands), Philip had Carlos placed in solitary confinement where he alternated between self-starvation and heavy binge eating. He died six months later, July 24, 1568, at the age of 23. It was rumored that he was poisoned on the orders of Philip.

Philip II (or Felipe in Spanish) was born in 1527. At the age of 16, his father Carlos V made him the Duke of Milan which began his governing of the most extensive empire in the world. With Carlos’s abdication, he became King of Spain at the age of 29. During his reign, Spain reached the height of its influence and power.

His empire included territories on every continent then known including the Philippines that were named for him. The expression “The empire on which the sun never sets” was coined to reflect this extent of his possessions. Among his wives was Mary Tudor, the Queen of England (aka “Bloody Mary”), which placed him as King of England while she lived.

He was also famously considered as husband for Mary’s sister, Elizabeth I. Despite his connections to England, as King of Spain he later lead the “Spanish Armada” against England resulting in his most significant defeat. Philip was born in the Spanish capital of Valladolid about 120 northwest of Madrid and where Verdi’s librettists originally set Acts III and IV of the opera [see below].

Philip’s marriage to Elisabeth and the two daughters they had gave him claim to the French throne. There is no evidence that there was any romantic attachment between Don Carlos and Elisabeth and she was apparently quite devoted to her husband, Philip.

She died following a series of miscarriages when she was only 23, the same age as Carlos and coincidentally just two months after Carlos died. Philip suffered considerably from gout and died a very painful death from cancer in 1598 at the age of 71.

The King’s devotion to Catholicism was so extreme that his bedroom in the Escorial was next to the chapel. His supporters presented him as a gentleman full of piety and Christian virtues, while his enemies depicted him as a fanatical and despotic monster intent on inhuman cruelty and barbarism.

These cruelties were more directly attributed to the Spanish Inquisition even though it was the King who appointed the Grand Inquisitor, the lead official of the Inquisition. In 1478, Pope Sixtus IV, for whom the Sistine Chapel was named, gave the Spanish monarchs exclusive authority to name the inquisitors in their kingdom.

The Spanish Inquisition was ostensibly founded for the purpose of determining heresy; anyone not Catholic was considered a heretic. In actuality, it was originally created to rid Spain of Muslims and Jews, later on Protestants, i.e., non-Catholics. The Spanish Inquisition was the archetypal symbol of Catholic intolerance and ecclesiastical power. It was not definitively abolished until 1834.

The Grand Inquisitor at the time of the opera was Diego de Espinosa who served from 1566 to 1572. Philip considered him his best-ever Minister. Interesting fact: de Espinosa was prematurely pronounced dead. As the embalmer was opening his chest cavity for the embalming, he revived and pushed the knife away. He died from the incision.

Philip’s father, Carlos V (Carlo Quinto, no relation to Zachary, but the same character as in Verdi’s Ernani), born in 1500, was the King of Spain from 1516 and the Holy Roman Emperor from 1519 until his voluntary abdication in 1556. While Philip inherited Spain and its dominions, the Holy Roman Empire went to Carlos’s brother Ferdinand I.

Carlos was only 54 when he started to abdicate his various dominions, but after 34 years of energetic rule, he was physically exhausted and in poor health and sought the peace of a monastery. Among other maladies, Carlos suffered from an enlarged jaw, a deformity that became considerably worse in later Habsburg generations, giving rise to the term Habsburg jaw. From paintings, we can see that both Philip and Don Carlos inherited the jaw as well.

This deformity was caused by the family’s long history of inbreeding which was commonly practiced in royal families of that era to maintain dynastic control. Carlos V’s struggle to chew his food properly resulted in his usually eating alone. He suffered from epilepsy and like his son was seriously afflicted with crippling gout. In his retirement, he was carried around in a sedan chair.

Carlos retired to the Monastery of Yuste in Extremadura about 150 miles west of Madrid. This is the monastery at which Acts II and V of the opera take place. At least among his family, it was no secret that Carlos was not dead but retired and Philip and other well-known people visited him there often until his death from malaria at the age of 58. Initially, Carlos was buried at Yuste but 26 years later, his remains were transferred to the Royal Monastery of San Lorenzo in the Escorial.

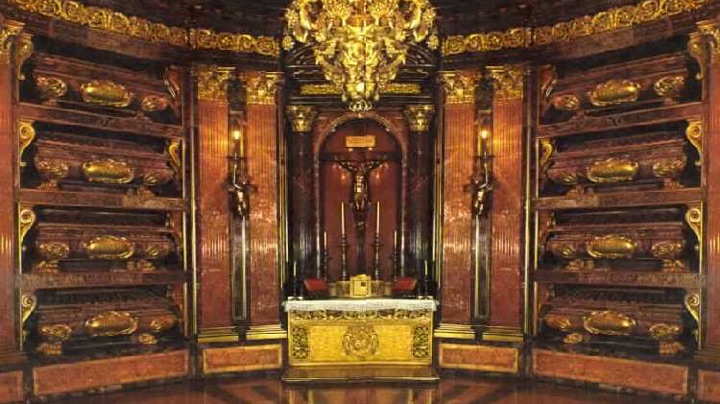

The burial chamber of the Escorial. The coffins of Carlos V and Phillip II are the upper two on the left.

Carlos V’s and Philip II’s reign saw a flourishing of cultural excellence in Spain, the beginning of what is called the Golden Age and elsewhere as the Renaissance, creating a lasting legacy in literature, music, and the visual arts.

The Renaissance bridged the Middle Ages to Modern History. Carlos’s and Philip’s reigns covered the Age of Exploration; Columbus had sailed from Portugal in 1492; under Carlos’s reign, Magellan circumnavigated the world in 1522. Their reigns spanned a century that included Michelangelo at one end and Shakespeare at the other. [Most of these facts are with gratitude to and courtesy of Wikipedia.]

LOCATIONS: Even ignoring their historical background, each of the principals of Don Carlos has a rounded individuality that is nowhere surpassed in the Verdian canon and no other work of his explores such a variety of human relationships. Still, it is not only the humans who spring to life, but the locations.

I had probably not really read a synopsis or closely followed a libretto since the Solti/Decca recording came out about half a century ago and that was my primary introduction to the work as I’m sure it was for many. Over time, locales and times had blurred and now I found it very confusing, and certainly enlightening, to study various synopses as well as libretti and scores of all the versions.

Something I noticed immediately was that the revised Italian score says that Acts III and IV take place in Madrid, while the original score states Valladolid. The royal court moved around frequently at that time, but the official royal seat remained in Valladolid. A fire there in 1561 caused the capital to be moved to Madrid but not to El Escorial as many people seem to think.

The cornerstone of the Escorial was laid in 1563 and was not completed until 1584; the events of the opera supposedly take place in 1568 and it is unlikely that any of the opera takes place in a palace in the early stages of construction. In fact, Philip had collaborated with the design of the palace and monastery.

The Escorial is 28 miles northwest of Madrid. Not only was Philip buried there, but his father, Carlo V’s remains were transferred there from San Juste. According to the extensive notes in the critical edition score, a lot of these facts had escaped the original librettists, Joseph Méry and Camille du Locle, including that in the original libretto the Cathedral in Valladolid in front of which the auto-da-fé of Act III takes place was not open until 1585.

As for the Escorial, I and perhaps the librettists can rationalize that Philip’s reference to the Escorial in his monologue is the place where he and all the rulers of Spain will be buried and not as a place where he is at present.

Schiller places his first act in Aranjuez south of Madrid, but the palace there was also designed by Philip and was not completed until much later. The Italian translation of Achille de Lauzières, which was used in the autumn of 1867 for Bologna, the first Italian performances, moved the setting for the auto-da-fé to the basilica in Madrid, “Our Lady of Atocha,” in which all the ceremonies of the royal family traditionally took place.

Add to the confusion that the notes date the action as taking place in 1560 while other sources state it as 1568, the year of Carlos’s death. Correctly then, Acts III and IV take place in Madrid. The palace there known as the Alcázar had been there since the 9th century. Madrid has mostly remained the capital of Spain to the present day.

All this might not make much difference to the average operagoer, but Don Carlos is set in a given time and place and concerns historical people and to a lesser degree, historical events. To me as a set designer and occasional director, I would want to – would have to first know these facts.

Besides, I also found them very interesting. It never occurred to me that the second scene of Act II immediately follows the first scene, both in the monastery of St. Juste; I had always assumed that after the visit to Carlo V’s tomb, they just returned to the palace.

Now if I were directing it, I just might allow for the one scene to dissolve into the next. Likewise, all the scenes of the following acts all take place almost all closely following each other or perhaps over the course of two or three days. All that has never been clear to me in any staging.

So if there is a correct, historical timeline to be followed, it is that Act I takes place in the woods of Fontainebleau in the year 1559 (the year Elisabeth and Philip were married and when both Elisabeth and Carlos were 14 and Philip was 32); the rest of the opera takes place more-or-less nine years later in 1568, the year of Carlos’s death, with Acts II and V at the monastery of St. Juste in Extremadura and Acts III and IV in Madrid at the Alcázar and for the auto-da-fé scene in front of the Basilica of Our Lady of Atocha.

Schiller’s play and Verdi’s opera are no more historically accurate than Shakespeare’s histories or any number of other literary and musical works. It should be noted that Schiller’s play, first produced in 1787, was based on a 1672 book Don Carlos, Nouvelle Historique by César Vischard, the Abbé de Saint-Real (1672). It is here that the fictional secret passion, an unfounded rumor, between the real life Carlos and Elisabeth was first penned.

But like Shakespeare, Schiller and Verdi were more concerned with a dramatic or poetic truth and willing to forego mundane facts to achieve it. However, I strongly feel that Verdi and the librettists could not entirely ignore Carlos’s sanity, no matter how theatrically questionable it might be.

Otherwise how can one explain the character’s permanent state of vulnerability or the fact that he becomes utterly distraught at the slightest provocation? The indications in the score make this clear: “in a dying voice”, “in exaltation,” “in delirium,” “he falls in a swoon on the grass.” Carlo’s father calls him “insensato” – madman. Even his best friend Rodrigo refers to him to Eboli as delirious and mad.

How a director interprets this is entirely his choice. No Carlos that I have seen is a total whack-job, but I would say that Rolando Villazón in a 2004 Amsterdam production directed by Willy Decker comes mighty close. In the least stylized version, the Met’s 1983 directed by John Dexter, Placido Domingo lives up to his name and is the most placid showing no particular signs of insanity other than the faint that is required by the libretto during the Act II duet with Elisabeth (though that certainly has never stopped a director before).

This “faint” has always struck me as peculiar and out of character for a “hero.” It is perhaps the librettists’ acknowledgement to the fact that Carlos was a person with epilepsy.

More background to Don Carlos in Part 2!

Comments