Budden, who is clearly on the side of it being performed only in French (and all his examples are in French which makes it very difficult to locate what he is talking about in the standard Italian score or libretto) offers one example that I can understand: during the trio in the Garden scene at midnight, Eboli’s climatic statement to Don Carlos is “You love the Queen!” It is a succession of Fs with the penultimate and emphatic note raised an octave.

In the original French, it is “Vous aimes la Reine!” with the emphasis on the ‘Rei’ of ‘Reine’. In the Italian translations, “Voi la Regina amate!” the emphasis goes on the ‘ma’ of ‘amate,’ emphasizing the word love instead of queen which changes the importance of the meaning to whom Carlo loves (Elisabeth the Queen), not just that he loves someone else (Eboli).

Just because it’s correct doesn’t make it better. To me, everything sounds better in Italian, and a lot of people are going to say that all Verdi sounds better in Italian; that would include Les vêpres sicilienne Verdi’s only other opera originally written in French (Jérusalem, Le trouvère, and La force du destin being more-or-less translations of previous Italian operas). I also think that much of the opera is more effective in Italian; using the example again from above, when Philip calls Carlos “madman” during the auto-da-fé scene, it has far more bite calling him insensato than insensé. At least to me.

The conductor Antonio Pappano who has conducted both French and Italian versions says that the French is more idyllic, poetic, while the Italian is “slightly more meat and potatoes.” However, my overall feeling is that it sounds better in Italian, but it sounds right in French. The French contributes so much to the score’s particular dramatic coloring. No one can win this argument. Therefore, in most cases, it’s going to come down to the version everyone already knows: Italian.

I assume that the final decision as to what version and in what language is up to the opera company and its general manager and that the conductor and the stage director must abide by that. Of course if you’re Herbert von Karajan you’re all three and come up with an abominable choice – more on that later.

After choice of language, the next decision is which version. Even before a decision is made as to how to portray Carlos’s sanity or the even greater question as to Carlo V’s relation to the plot (which I’ll get to shortly), certain other decisions must be made. Verdi composed Don Carlos in French for the Paris Opéra.

The great composer was determined to set his mark on the French “Grand Opera” style, and indeed he did far surpassing any grand opéra that had come before or to come after. The style had elements that were de rigueur, primarily that all the elements had to be large-scale: the casts, the orchestras, the costumes, the sets. Plots were usually based around dramatic historic events.

A most notable feature was that the opera had to feature a ballet, but not before the second act which would have otherwise interfered with the regular meal-times of the wealthy patrons of the Opéra most of whom were more interested in the dancers personally than in the opera. Wagner’s Tannhäuser failed at its Paris première because the ballet was right at the beginning of the first act.

For this reason, performances could not begin earlier than the prescribed hour. And because the last trains left shortly after midnight, the performance could not run late. By the final rehearsals, it was realized that Don Carlos ran far beyond the allotted time and Verdi was forced to make cuts. He spent the next 20 years trying to fix the problem resulting in lost materials and a myriad of versions.

It is due primarily to the efforts of the much-missed former critic of the New Yorker, musicologist, and libretto translator Andrew Porter and the German musicologist and researcher Ursula Günther that these lost materials were discovered. Having seen the autograph score, Porter deduced from markings of occasional opening and closing bars that pages had been removed.

In 1969 at the Bibliothèque de l’Opéra he was able to see the original orchestral parts and found the missing passages. Prying or snipping open the pages that had been stuck down or stitched in 1867, Porter was able to reassemble, line by line, a good deal of fine music by the mature Verdi which had remained unknown, unseen, for over a century. In 1970, a new critical edition of the score was published.

For the sake of clarity, following is a list of the primary “versions” with some other important dates:

- 1866 (1) – Original – as composed before the cuts of the first performance.

- 1867 (2) – Paris Original – March 11, 1867 at the Salle Le Peletier (Théâtre Impérial de l’Opéra) with the first cuts; further cuts were made during the initial run.

- 1867—Bologna (27 October) – Italian premiere (in Italian and including ballet) at the Teatro Comunale di Bologna.

- 1872 (3) – Naples – same as Paris except for alterations in the Posa/Philip duet and final Carlos/Elisabeth duet.

- 1884 (4) – Milan – January 10, 1884 at La Scala—new 4-act version with revisions and without original Act I or ballet.

- 1886 (5) – Modena – Milan version with addition of 1867 Act I (w/o the “hunters” scene). This restores the epic scale of the original conception, while retaining the masterful rewriting from two decades later and normally is standard.

- 1969 – 2nd Verdi Congress of 1969 and discovery of lost parts of the original score by Ursula Günther and Andrew Porter

- 1970 – publication of the critical edition score.

Now that all the missing material has been discovered and published (even it that was 45 years ago!), without question, and in anticipation of much debate, I strongly feel that the original version, i.e., the one Verdi composed and before any cuts were made, is the only acceptable version albeit perhaps with a few of the revisions he made that were not based on time constraints. Obviously, there are plenty of eminent musicians who do not feel the same. But, I will attempt to make my case.

We can only assume to what extent Verdi’s abridgment of his original work was prompted by the need to save time, and how much it was prompted by artistic considerations. However, music by the mature Verdi is too fine to leave unperformed.

For the record, a complete Don Carlos with all the cuts open runs about 3:50, about the same length of time of a Tristan or a Walküre or a Guillaume Tell. Any professional critic who thinks that this would be too long, should be made to sit through an eternity of Parsifals or Meistersingers (not that there’s anything wrong with that).

Regardless, Verdi in his revisions did place an emphasis on concision and most of the cuts were an improvement musically. The opera with its ballet, grand finale, and crowd scenes, was conceived as a work of spectacle. Much of this Verdi added to Schiller’s play, whose complexity was already well-known; Schiller himself had similar problems as did Verdi in reining in all the elements and spent almost as long as Verdi did making revisions.

Verdi borrowed from a more recent French play (Eugène Cormon’s play of 1846, Philippe II, Roi d’Espagne) and added the first act that served as a prologue to the drama and the auto-da-fé, that Schiller only alludes to, as the monumental Act III finale. Also added were the obligatory ballet and the uprising concluding Act IV.

Verdi also altered the ending, but that is a separate subject. All of these additions were to meet the demands of the grand opéra style; length was an unwitting result. It is the operas’s originality that Verdi uses these added elements to balance and probe into the interrelationship between individuals and community, the private lives with the public lives.

The most obvious and largest cut to this score has been the original, entire Act I, which more-or-less gives us the “Milan” version. I find it a desecration; one is forced to listen to it if not accept it when there are so many tremendous performances that use that version.

Comparing Don Carlos again to the Ring, performing the opera without its first act is like performing the Ring without Das Rheingold and performing that act without its opening scene, i.e., the “hunting” scene, is like performing Das Rheingold without the Rhinemaidens scene.

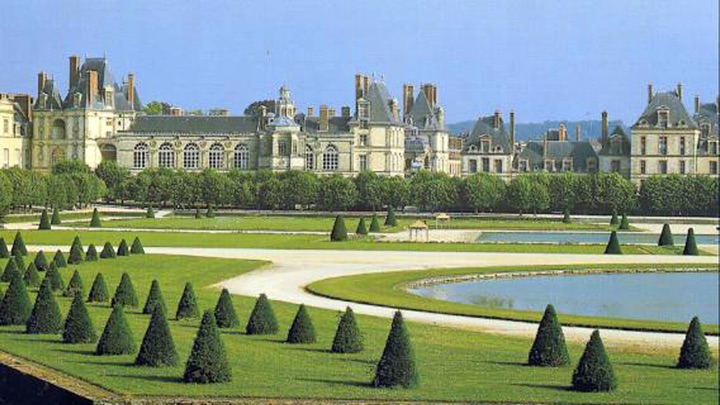

The act, known as the “Fontainebleau Act,” opens with a series of acciaccature (an ornament/grace note that is one-half or whole step higher or lower than the primary note and that takes up no time value within a measure). These notes can be considered as a lament, and in variable form as a theme that is used repeatedly throughout the opera initially associated with the poverty and hardship of the woodcutters and hunters and their families but later on with the church (the monks, the inquisition) in the preludes to Acts II and V but most especially with the prelude to Philip’s monolog in Act IV. It immediately establishes the opera’s tinta which was Verdi’s expression for the color of the music.

Coincidentally or not, this “lament” motif is very similar to the lament or “woe” motif that Wagner was composing for the Ring at about the same time, though in Wagner’s case the grace note of Verdi became a full note for Wagner. Musically, the act goes on to contain ideas which assume full fruition later on but when the scene or entire act is cut, lose much of their identity.

In the same way, the structural curve of the opera is broken; the original version begins with Carlos and Elisabeth’s first meeting and the opera ends with their final separation. I suppose it can be argued that without the act there is the curve of starting and ending in the monastery but it leaves a number of unexplained questions and is no substitute for seeing Carlos and Elisabeth meet and begin to love.

Within the preliminary “Hunters Scene” we, and Carlos, see Elisabeth for the first time and along with the ensuing duet, it is the only time we know her as she really is: before the oppression of the Spanish court and her position as Queen. Not only do we see her enjoy games or hunting with her court, but we see her interact with the French people and her generosity and consideration for them. The music is playful and frivolous and combine to suggest an impossible idyll for Elisabeth and that she will recall in her final aria.

It is essential in the staging that we see Elisabeth and Carlos like adolescents (historically, they were actually 14 years old) who find themselves momentarily free of any social context in the symbolic space of a forest, only to be crushed immediately by the society they must inhabit. Their duet is placed between two public scenes that motivate her self-sacrificing decision to seal the peace treaty, one of the destitution of the starving French peasants exhausted by war and the other by the court on behalf of the King of Spain.

It is in this moment yielding to the pressure of her decision that we see the change in Elisabeth and the obligation she must face not only as a princess but for the fate of her people. Her love for Carlos is a misfortune that now as Queen she can do nothing about but she can’t deny it either. Deprived of happiness, Elisabeth at least has her new role as Queen to cling to while Carlos, cut adrift, self-destructs.

The other characters we meet in the first act are Thibault/Tybalt/Tebaldo, Elisabeth’s page, and le Comte de Lerme or Count Lerma. I’m pretty sure Verdi and his librettists did not consider Lerma as anything more than someone to stand around to make announcements. Nevertheless, he is or at least can be in every single scene of the opera.

In the Schiller play he has much more significance and he along with several other courtiers not in the opera sneak around betraying everyone else; but then in the play no one is to be trusted. Even Elisabeth is complicit in sneaking letters to Carlos in her support of Flanders. For that reason and not only because she is a foreigner, she is pretty much despised by everyone. In the opera, Elisabeth realizes her position and how alone she is when the King dismisses her Lady-in-Waiting in the second scene of Act II.

As for Count Lerma, when we first meet him he is there as the Envoy from Spain to the Court of the French King Henry. Carlos has said right at the beginning that he has snuck out of the court of Philip and has hid unnoticed in the ambassador’s suite. Carlos has left Spain believing that he is betrothed to Elisabeth. Lerma has left Spain knowing that Elisabeth will marry Philip.

Not in the play or the opera is the fact that in 1556 before Philip had returned to Spain and, prior to 1559 and his subsequent marriage to Elisabeth, he had signed the treaty with France that would have included marriage to the daughter of the French King. That is not necessarily important to the plot but it’s highly unlikely that Lerma did not know Carlos was in the entourage and this is the first betrayal we come across.

One of the fascinating things about Don Carlos is that it can be looked at from different perspectives and different characters can be made to be the protagonist. Usually it’s Carlos, often it’s Philip. In the questionable 2004 Vienna production, it’s definitely Eboli – we’ll also get to that later. But, I think a very strong case could be made for looking at the opera from the point of view of Count Lerma … Just a thought!

From this prologue, we jump ahead to the first scene of Act II. Presumably, it is nine years later, 1568, the year of both of the deaths of Carlos and Elisabeth. It is set at the monastery of Saint-Just (San Jerónimo de Yuste) in Extremadura in a mountainous region of Spain some 150 miles from Madrid. We first encounter a friar who is presumably Carlo V or perhaps his ghost. (I’ll save discussion of this character until later as it involves the controversial ending of the opera.)

Instead, we’ll talk about the most controversial yet the only supposedly fictional character in this epic, Rodrigue/Rodrigo, the Marquis of Posa, the idealistic freethinker who alone dares to speak the truth and becomes both the play’s and the opera’s intellectual center. This purely fictitious Marquis of Posa is a walking anachronism spouting the libertarian ideals of Schiller. Perhaps Posa has a lack of political realism for the age, but he is certainly a fanatic about it.

No sooner than Posa has said to Carlos, “Hello – long time no see” than he harangues Carlos with joining him in his fight in support of Flanders. However, Rodrigo seems to be one of those people whom everyone likes instantly. The most unlikely people confide in him, at least Carlos, Elisabeth, Eboli, and Philip do.

Whether or not he is worthy of their trust is open to debate. Like many confidantes, he doesn’t always listen and his mind is really only on his own concerns. His paradox is that he finds himself in the role of confidant to the very source of the massacre he protests: the King. His zealousness regarding oppression and freedom puts him at odds with the church and his views are regarded as heresy. This is why Philip warns him of the Inquisitor.

Clearly, Posa Verdi saw as a consistent force throughout the work. The major revisions the composer made were to the two Posa duets, the one with Carlos at the beginning of the second act which had three versions, and the one with Philip at the end of the act which went through four versions. To my knowledge there is no recording of the middle versions of either of these duets.

The Carlos-Posa duet is mostly a case of shortening; in the original scheme the scale was larger, and the independence of the suffering people on the rulers emphasized at the start. Verdi removed a lot of what Posa said as it was said to greater effect in the later duet with the King. Verdi also removes some more traditional-type duet singing in both duets making them both more dramatic dialogues.

In the first duet, not much is lost, but clearly in the duet with Philip, a great deal is gained. Gone are all vestiges of singing together in the usual manner. The warning of Posa as to how Philip will be regarded and the warning of Philip to Posa regarding the Inquisitor are far more emphatic. Presented are the political arguments of Philip and Posa: the conservative vs. liberal. It should be noted that there were three reworkings of the passage where Philip outlines his “program” of repression: “Blood is the price that’s paid for peace in my dominions.”

Verdi, knowing the importance of this scene, was emphatic that the portrayers of these parts understand that they were representing two great principles: conservatism vs. liberalism. It seems strangely out of character that Philip asks Posa to help him in his personal life by observing his wife.

The second scene immediately follows the Carlos-Posa duet within the monastery; it is set in the garden just outside the gates; the layout is a bit vague. The directions in the critical score says that the first scene takes place in the cloister of the convent of St. Yuste with the tomb of Carlo V seen through a gilded grille. There is a door leading to the exterior. At the back, a garden with large cypress trees.

The second scene says a delightful spot outside the monastery gates which are at the back. A cloister to me means an outside area surrounded by a walkway with arches that runs along the walls of a building.

There is no grand tomb in the middle of it. I suppose “cloister” means different things to different people yet I’ve never seen a production that indicates the first scene is taking place outside. In my mind if I were staging this, I would have a set that moves laterally like the marvelous set for the Met’s Rodelinda. As the first scene which would be inside ends, Philip would remain inside to talk with his father and as Posa exits, the set would move off and he would enter the outside “cloister” as the next scene begins.

Ignoring the historical fact that Carlo V did die for real in 1558, one could stretch that fact for another decade at least to the time of the opera, it is known that Carlo V was visited in his pretended “death” by many people, especially Philip. Even Carlos would have known this. Moving a royal court some 150 miles through the mountains in those days had to be quite an undertaking. Philip would have had no good reason for going to St. Yuste other than to talk to his father, the former king.

Meanwhile, Posa will have started the next scene where the ladies, who are not allowed into the actual monastery, are enjoying themselves and soon to be joined by Elisabeth, the one woman, as Queen, who is allowed entry; she would have remained inside to pray especially after the shock of seeing Carlos.

In the second scene, we meet Eboli. Ana de Mendoza y de la Cerda, Princess of Eboli, Duchess of Pastrana, was a Spanish aristocrat born in 1540 and died in 1592. At the age of 13 by recommendation of Philip II, she married Rui Gómes da Silva, probably not the same one from Ernani as that opera supposedly takes place in 1519. This Silva was a chief councilor and favorite of Philip. Eboli and Silva had ten children.

There are several portraits of her, all with an eye patch. Allegedly during her early adolescence, she lost her right eye in a fencing duel with a page. Traditionally, she was always played with the eyepatch but for some reason other than perhaps it’s unnecessary to the plot and is distracting, it has disappeared. It now seems fashionable instead, that during the course of “O don fatale” she scratches her eye out.

I mentioned earlier that in the 2004 Vienna production, Eboli seems to become the main character. I guess now’s as good a time as any to follow up on that. I’m sure I’ll have more to say about this later when I get to talking about recordings. For reasons other than its production, it is the only staged version of the complete, original, pre-Paris première, en français, as-Verdi-intended opera. For that reason alone, it is a must.

However, the staging is fascinating while at times, I repeat, atrocious. It is the only opportunity to see the ballet staged and that opportunity is squandered on a ridiculous conceit with the projected title: “Eboli’s Dream.” Whatever constantly changing dates the production takes place in now become the 1950s; Eboli and Carlos are married and the in-laws are coming for dinner. Eboli burns the dinner and Posa shows up as a pizza delivery boy. Don’t ask!

Following that is what used to be the auto-da-fé scene. Now it is a political rally with protestors throwing pamphlets down from the balconies. Actually, this scene almost works – at least it puts the plot into a light that can be associated with events today. Whatever.

For all that, it is the following scene that is what focuses the most attention on Eboli: the so-called closet scene. In this production there is no furniture. Pillows and clothes are scattered on the floor. Eboli has obviously spent the night with Philip having delivered Elisabeth’s jewel box to him. Philip mostly sings his monologue directly to her. This actually works. As the blind Inquisitor enters, Eboli is trying to gather up her clothes and the Inquisitor steps on her cloak just as she is trying to pull it away. The tension is unbearable added to what is already a tense scene.

At the end of the scene, the Inquisitor has smelled her presence. This supplies reason enough for her death after the uprising in the following scene clearly at the instigation of the Inquisitor. Eboli is still in the room hiding behind what passes for a door to witness Philip’s attack on Elisabeth. Not surprisingly, the whole scene ends with one of the times when Eboli scratches her eye out. It is brilliant theater no matter what anyone might think of what it has done to Schiller’s or Verdi’s intentions.

Meanwhile, back at the monastery… One of the many problems I find with the 4-act version is that the central duet for Carlos and Elisabeth seems to come much too soon. This is not music that is introductory but of established themes; we’ve gotten to “mature” music for which there has been no set up. Something sounds wrong. Unless we have heard the duet in the original first act as Carlos and Elisabeth meet and fall in love, the subsequent reminiscences of it no longer function as such and the sense of nostalgia is lost.

Additionally, the early duet with its essentially uncomplicated nature makes an effective contrast with the more tortuous encounters between the two lovers later on. This is music of passion both overt and suppressed and there is no logic unless we understand that passion. In some productions I watched, Philip has entered during the end of the duet and seen his son and his wife and has jumped to an ostensibly wrong conclusion. It’s very effective. I

n some cases, unless it has been extremely carefully staged, Elisabeth exclaims Tebaldo’s line announcing the king: “Le Roi/Il Re!” It might not be legitimate, but it works. It is Philip’s admonition and her subsequent aria that makes Elisabeth realize the full extent of how alone she really is. The act concludes with the Philip/Posa duet, which we’ll consider a little later.

Comments