The cast was Linda Kelm, Nicola Martinucci, Barbara Daniels, and Kevin Langan conducted by Myung-Whun Chung in what I believe was his U.S. Debut. Eddie Albert (of TV’s Green Acres fame), fresh from having appeared in the Luciano Pavarotti rom-com-fiasco, Yes, Giorgio, was the Emperor Altoum.

You can hear excerpts from most of the performance (minus the finale of Act One and some connecting bits) below. The sound is spotty in Act I but by the time Linda Kelm shows up, the sonic clouds have cleared and you can hear how formidable she was. So formidable, in fact, that six years later James Levine hired her as ‘High C’ Helmwige when the Met made their studio Die Walkure. She was a Seattle Opera Brünnhilde in the early years of their ‘Pacific Northwest’ Ring Cycles and sang Puccini’s Principessa around to great acclaim and made a good career. However, her entire Met career consisted of six ‘In the Parks’ performances of Turandot the year of the Walkure recording and one main stage Siegfried Brünnhilde. In spite of, or perhaps because of, her ample proportioning, she was one of those very good singers who just never became a ‘star’ for one reason or another. Rita Hunter syndrome.

Barbara Daniels wasn’t one of nature’s born Liù’s but she was a fine Puccini stylist in her day and a sensitive actress. Just no ppp. As Timur, Kevin Langan hit a note so strong, in his outburst after Liù’s death, it literally resonated in my own chest. The only other time that ever happened to me was with Gwyneth Jones on a high-C. Nicola Martinucci barreled his way through the music in true Mario del Monaco fashion and it was thrilling (I knew nothing).

The San Francisco sets and costumes by Allen Charles Klein were loaned and a co-production from the Miami & Dallas Opera companies. The unit set features an enormous golden dragon rearing its head stage left with the Emperor sitting in its clawed foot 20 feet in the air. In its other claw center stage is an enormous luminescent pearl. It was from within this pearl that Turandot made her first, very misterioso (and only faintly translucent), Act I appearance. This production has traveled the earth since. I saw it in Baltimore a decade later, where it looked very bus-and-truck, and was mounted as recently as 2017 by Chicago Lyric Opera.

The story goes that Eva Marton sang a performance once somewhere when she was fighting a bug and was sick inside the pearl. Apparently, in spite of a thorough cleaning, that melody lingers on now for any soprano stuck inside it waiting to make her entrance.

The other thing I most remember from that performance was the sudden entrance of the organ in the final pages of Act Two. We were in the orchestra section and I felt it through my feet(!), The War Memorial being one of the few theaters with an actual pipe organ. You don’t usually even hear it on recordings very often (and I certainly hadn’t noticed it) but suffice to say it was mind-blowing.

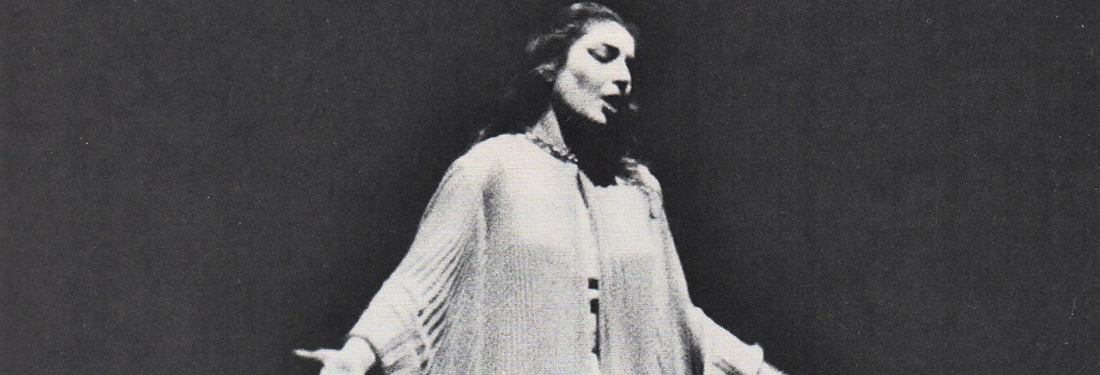

But the San Francisco Opera performance I would have loved to have attended was sadly before my ferocious fandom began and that was the 1977 opening night when Montserrat Caballé (in her local debut) and Luciano Pavarotti made their joint role debuts as Turandot and Calaf in a production designed by Jean-Pierre Ponnelle.

The long-suffering Liù was Leona Mitchell who had already made her San Francisco debut as Micaela in Carmen in ‘73 (after matriculating in the Merola program) and her Met debut in the same role two years later, starting a long association with both companies. Her Liù is a great assumption of the role which is sometimes handed to sopranos who have the Italiate slancio but lack grace up above.

I adored her voice and she recorded a glorious solo debut CD for Decca “Presenting Leona Mitchell” which has found a new home on the Eloquence label. I finally got to see her live in San Francisco in ‘91 as an absolutely heartbreaking Suor Angelica to the rapacious Elena Obraztsova and her three voices.

It was a double bill production with Pagliacci that was originally supposed to star Mirella Freni in her role debut as Angelica and then Pavarotti in his first staged Canio. I’m not certain how it all fell through, but in the end Mitchell came to the rescue and the belated U.S. debut of the great Russian tenor Vladimir Atlantov was hastily arranged in the Leoncavallo. Naturally, a telecast was planned that was canceled as well. Three years later Freni would record the whole Trittico for Decca (at the age of 58, perhaps a little too late in the career) and Pavarotti finally sang Canio, exactly twice on stage at the Met in 1994, at the tender age of 56.

Giorgio Tozzi held down the bass line as old Timur. Plus, singing one of Turandot’s handmaidens, in her first year of the Merola program, is the young Carol Vaness. Riccardo Chailly, still wet behind the ears at 24 (!), was making his U.S. debut and the production was a scandal, so gather ‘round.

The story goes that General Manager Kurt Herbert Adler had a wealthy donor on the line who was going to underwrite a new production for the company by an Italian designer whose name I’ve never been able to unearth. When that fell through, he turned to Jean-Pierre Ponnelle, who had a history with San Francisco Opera and who had recently directed a production he himself had designed at the Opera du Rhin in Strasbourg.

We now forget that in the 70s and 80s, Ponnelle was the absolute height of the regietheater avant-garde. I remember stories of a famous mezzo walking out on a production of Cavalleria because he wanted her to sing with a baby bump. His 1975 production of Wagner’s Flying Dutchman for San Francisco, which was imported to the Met a few years later, staged the entire opera in one act (as was the composer’s intention) and made it the ‘dream’ of the Steersman, who also played Erik (not the composer’s intention). Apparently the production was brought over sight unseen and Francis Robinson talks in his book on the history of the Met how it roused the audience to its collective feet ‘cheering and jeering.’ It was very high-concept for the Met at the time, but literally the same year that Harry Kupfer’s production premiered at Bayreuth, so Ponnelle’s was relatively tame by comparison. Needless to say, where the European press had loved Ponnelle’s Strasbourg Turandot, here in the U.S. folks were aghast and here’s why.

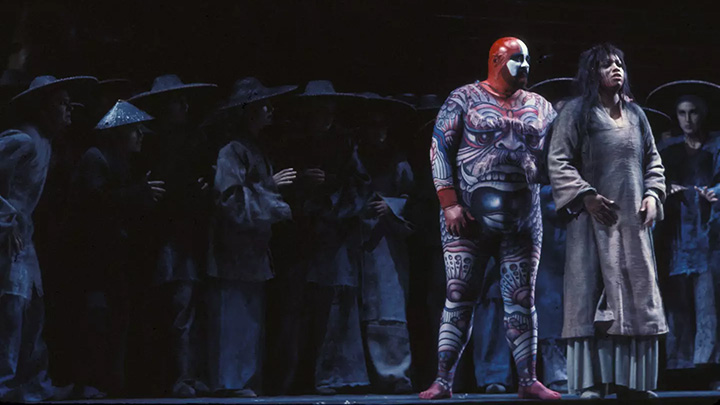

The first act featured a 30-foot tall, golden female buddha-style statue, with ivory face, bare-breasted, and arms folded. When the people of Peking call out for mercy for the Prince of Persia the arms unfolded to reveal La Caballé as she gave the executioner the fatal gesture. The entire production took place at night and, as always with Ponnelle, the colors he chose tended to monochrome (in this case mostly black, gold, dark blues and red). The savageness of the story was highlighted in the staging with the popolo abusing the Prince of Persia from the curtain’s rise and Turandot being followed around by two dwarfs in leather (their real purpose was actually to give the soprano balance as she descended the stairs in Act II). Bamboo hats abounded for the chorus.

At Liù’s death in Act III, the chorus, afraid of her avenging ghost (mentioned in the lyrics), left her body on the stage to the consternation of many in the audience. Eyebrows raised even higher when, after the vanquishing kiss, Calaf ripped Turandot’s white ceremonial robe off to reveal a red negligée underneath as bloody tears flowed from the eyes of the golden idol. It was nicknamed the ‘Vegas’ Turandot.

Jean-Pierre Ponnelle was occupied elsewhere so Nicolas Joel, then an Assistant Director in Strasbourg, was assigned to oversee the revival. In spite of having learned the role five years earlier for the Decca recording, Luciano Pavarotti was having his usual difficulties with memorization and staying focused during rehearsals. He had been singing in San Francisco since 1969 and they were mostly used to his increasingly egotistical shenanigans, but nevertheless, Ponnelle was flown in to lay down the law with the tenorissimo and supervise some final rehearsals. Prince Charles was attending opening night, so more attention than usual was expected. The story goes that Ponnelle read our tenor the riot act in front of the entire cast, in Italian, to make certain he got every word. Things proceeded smoothly from that point on.

Señora Caballé’s journey to her San Francisco debut was slightly longer. Her first Turandot was scheduled for La Scala for a one-night-only grand gala commemorating the 50th anniversary of the premiere scheduled initially for May 13 of ‘76 eventually rescheduled to three days later because…La Scala. The fact that this date was random and had no relation to the original premiere of April 26, 1926 seemed to bother no one. A new production announced to be designed by Pier Luigi Pizzi failed to materialize in time and instead a revival of the famed Nicola Benois that Scala had mounted for Birgit Nilsson in ‘58 was hastily arranged with a week of rehearsals and a few delays, the outcome of which was that the scheduled Liù, Mirella Freni, was no longer available.

Come the gala night, when Turandot made her famous Act I appearance on the palace loggia, many in the audience noticed the lack of resemblance the Principessa bore to the scheduled soprano. This was because she was across the street in her hotel room passing a kidney stone. The performance went on without her.

Kurt Herbert Adler had already had one run-in with Señora Caballé and it hadn’t ended well for the new production of Norma he’d mounted for her San Francisco Opera debut in ‘75. Owing to follow-up surgery she needed due to a hysterectomy, she had had to cancel at nearly the last minute. Rita Hunter recalls in her autobiography receiving a crack of dawn phone call from Adler with the opening line, “How’s your Norma?”

Not being pleased with the early call she rejoined, “Fine luv, how’s yours?” Ms. Hunter was warming up for an impending engagement in the Bellini at the Met, so she cleared her schedule and had a triumph in San Francisco. New York, however, didn’t receive her as graciously, especially Donal Henahan, who opened his New York Times review: “To get it over quickly, Rita Hunter is not a satisfactory Norma in any respect.” After her success in San Francisco, Adler had offered Ms. Hunter three seasons of choice roles, including a brand new production of …you guessed it Turandot. Sadly, the offers dried up after her lukewarm reception in the big apple.

Señora Caballé and her legendary reputation of “only being available for a few cancellations each season” already preceded her. So, regular press releases were issued assuring everyone far and wide that rehearsals were going smoothly since gossipy opera fans were mindful of both the local Norma cancellation and the La Scala debacle. Adler reportedly made it clear to the soprano that if she didn’t sing, he’d bring her up on charges with the artist’s union. The staff walked on eggshells around her until her impish sense of humor finally won the day.

San Francisco pays tribute to this production on their webpage which includes some great photos, the essays from the evening’s program, including an interview with Licia Albanese (who was beloved in San Francisco and sang Liù to Leonie Rysanek’s Turandot in 1957), and the radio broadcast capturing the next performance. It’s been bootlegged on the Gala label for years but there’s an even better remaster of it on YouTube.

Listening to it again for the first time in a while, it surprises on a number of levels. First, I have to put bed to the longstanding rumor that the second act was lowered a whole tone so that Caballé could get through the role. Anyone with a pitch pipe can tell you that certainly isn’t the case. Both the soprano and the tenor are in white-hot voice and, especially in the last scene, really put a lot more emotion behind their phrasing than either of them used in the studio. A lot more. Like, it almost gets a little verista at times. It’s very exciting to hear both of them so involved and inspired by each other. He even takes the optional ‘C’ in the second act.

Caballé pulls out that magical pianissimo just when you wouldn’t expect it at the climax of her first aria. On the repeat of the line “Quel grido e quella morte!” she suddenly diminuendos down to almost nothing (after the B in alt, mind you) to show her great sadness at the death of her predecessor Lou-Ling. She’s unsparring with her voice throughout the riddle scene. After Calaf solves the second riddle and the crowd offers their encouragement her, “Percuotete quei vili!” is absolutely ferocious.

They also sing the full Alfano II finale with Caballé offering a magnificent “Del primo pianto”. She starts it with a mini-sob at the end of the proceeding phrase and then really digs into the words. It’s very individual and vulnerable and filled with pathos with a lot of contrasting dynamics. She does the vocal fade again at the repeat of “So il tuo nome.” She keeps lavishing phrase after phrase with her Bel Canto skills. Proving her studio recording of the leading role (which was released the next year but had been recorded just two months prior …oddly, with the Strasbourg forces and their chief conductor Alain Lombard) wasn’t a bag of audio engineers’ tricks as was whispered out loud in the press on more than one occasion then and since. Captured at just the right moment in her development, this performance may be among her greatest.

Chailly is galvanizing in the pit and in spite of his age, it’s apparent that everyone is trying to keep up. Especially since we know how much this tenor and soprano enjoyed conductors who followed rather than led.

Caballé had already recorded Liù to Sutherland’s Turandot for Decca in ’72, the gold standard that all others will be judged by forever more (and badly at that). At the time the critic Edward Greenfield suggested to the powers that be at Decca that they release an appendix album with Caballé singing “In Questa Reggia” and Sutherland in the two Liù arias. Sadly, that came to naught.

Yet they did meet again in the recording studio in 1984 to record Bellini’s Norma. Caballé, to almost everyone’s astonishment, agreed to learn the Seconda Donna role of Adalgisa for the recording and the opportunity to work with La Dame Joan again. Another great story is Caballé arriving on the first day of rehearsal with a huge floral tribute for Sutherland. Joan says, “Montsy, how kind flowers for the Prima Donna”. Caballé said, “Ah no Joan, flowers from the Prima Donna”.

Check out my survey of some favorite Turandot recordings here.

Photos: Ron Scherl

Comments