The album, Unexpected Shadows, features four complete song cycles, interspersed with a couple of standalone numbers – all accompanied by the composer himself at the piano.

Unexpected Shadows is a superlative artistic achievement. It is so rare to hear an entire album of vocal music by a living composer, and rarer still to hear it performed by a singer of Barton’s caliber.

I must confess that I’ve never been a huge Heggie fan. I find Dead Man Walking a little heavy-handed and Moby Dick a little drab. However, after hearing this album, I’ve become something of a Heggie convert.

The variety on show in these (beautifully crafted) chamber works is much wider than in the composer’s operas. Many of the songs on this album have an off-kilter, Off-Broadway jaunt – closer to William Finn than Puccini. If some of the parody numbers are little ham-fisted, this only highlights Heggie’s ability to build genuine emotional sentiment elsewhere.

Heggie’s greatest strength is his uncanny ability to write for voice: his vocal lines are intuitively constructed, betraying a predilection for the warm, comfortable core of the mezzo-soprano range and a lithe attentiveness to the nuances of the text.

And Barton gives this music her all, showcasing a formidable breadth of expressivity, perfectly suited to this repertoire. Vacillating between bluesy croon and silvery vocalise, Barton maintains a rich, opulent tone throughout, navigating even the most extreme changes in dramatic tone with flair and poise.

Every phrase is elegantly spun, every color delicately balanced and stylishly rendered. Even when shrieking “you sick, self-centered son of bitch!” on the album’s final track, Barton upholds a sense of sophistication and polish. To be able to sing with so much raw emotion and still maintain this degree of musicality is an impressive feat.

The last cycle on this album, drolly titled Statuesque, is a musical tribute to five iconic sculptures of women – including Henry Moore’s “Reclining Figure in Elmwood”. (Listening to this number, it struck me that Barton’s voice is not dissimilar to a Henry Moore sculpture: grand and monumental but never brash or ostentatious; eccentric and offbeat but always graceful and tastefully molded.)

These sculpture-inspired tracks are full of character: from the mournful dirge of Alberto Giacometti’s “Standing Woman” to the playful vaudeville of Picasso’s “Head of a Woman”. Heggie has done a marvelous job of anthropomorphizing these works of art, but Barton has done an even better job of humanizing them. She approaches these songs with humor and honesty, finding moments of warmth and restraint in amongst all the burlesque.

This is preceded by Of Gods and Cats, a whimsical, scatty setting of two poems by Gavin Geoffrey Dillard (most famous for his racy homoerotic poetry). Barton’s performance here is light and frothy; Heggie’s playing is terse and exacting.

The second of these songs, which tells the story of a spiteful, destructive God being reprimanded by His mother, places pianist and singer in playful lockstep, dancing around each other in angular, lopsided phrases. Barton seems utterly at ease in amongst all this musical and poetic complexity, sailing through the song’s quicksilver shifts in mood with great panache.

The first cycle on the album, The Work at Hand, was commissioned for Barton herself for a performance at Carnegie Hall in 2015. The cycle certainly seems well suited to Barton’s voice, with long, languid phrases anchored in the sumptuous middle of her range.

The text, by the late poet Laura Morefield, is a poignant reflection on her battle with terminal colon cancer. It is sensitively delivered by Barton, who forgoes the theatrics of the other cycles in favor of a plainness and a sangfroid, well allied with Heggie’s more austere setting.

Barton and Heggie are joined here by cellist Matt Haimovitz, whose anguished sul ponticello adds a welcome kick to the cycle’s more forceful moments.

The two standalone numbers are the least memorable tracks on this album. Awkwardly bookending the harrowing Work at Hand, they feel downright bland compared to the more colorful song cycles.

A (mostly unaccompanied) excerpt from The Breaking Waves – a song cycle commissioned for Joyce DiDonato based on texts by Sister Helen Prejean (of Dead Man Walking fame) – had a folksy charm, but Barton might have injected a little more gloss into Heggie’s meandering vocal writing.

An aria from Heggie’s recent opera, If I Were You, was all too repetitive and rendered with all too much vocal slipping and sliding by Barton.

The jewel in this album’s crown, however, is the song cycle Iconic Legacies: First Ladies at the Smithsonian – four songs sung from the perspective former presidential wives about various objects in the Smithsonian.

Eleanor Roosevelt finds hope and comfort in the mink coat Marian Anderson wore for her famed Lincoln Memorial concert; Mary Todd Lincoln reflects upon a nation divided as she considers the top hat her husband wore on the day he was assassinated; Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, contemplating a Christmas card signed by her husband just before his assassination, sings a gut-wrenching lament; and, finally, Barbara Bush waxes lyrical about her literacy campaign, undertaken in collaboration with the cast of Sesame Street.

This cycle was a standout – partly due to Heggie’s music, which strikes a much finer balance between the serious and the silly; partly to the texts (by long-time Heggie collaborator Gene Sheer), which seem to speak so eloquently to our own political moment; and partly to Barton’s performance, which so consummately and sympathetically embodies these historical figures.

After Melania Trump’s (truly repugnant) comments on her husband’s family separation policy were leaked last week, these songs have a strange political resonance. Barton, Heggie, and Sheer paint a portrait of four women whose most intimate personal relationships are uniquely tied up in political concerns.

This entanglement of the personal and the political underpins the entire cycle, embodied in Heggie’s music by a dizzying, swirling leitmotif woven throughout the four songs, and in Barton’s performance by a sense of immediacy and sincerity. It might encourage us to reflect on the huge amount of political capital tied up in this ostensibly apolitical position ahead of the upcoming election.

All in all, this is an outstanding recording. It may even be the best queer classical collaboration of the decade. If not, it’s certainly the must-have album of the year.

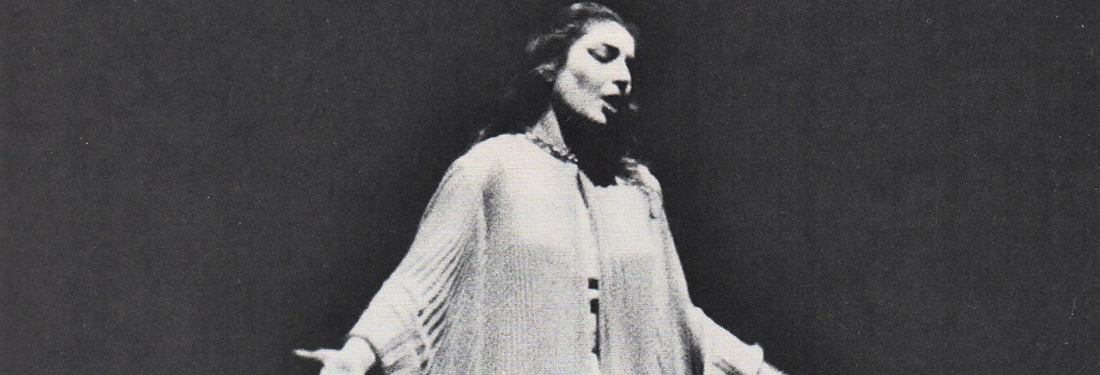

Photograph: Fay Fox

Merry Widow | Finger Lakes, NY | July 25-28

Geneva Light Opera’s production of Lehar’s The Merry Widow will feature prize-winning baritone Bryan Murray and soprano Alexis Olinyk in the superb acoustics of in the landmark Smith Opera House in Geneva, New York on July 25, 27, and 28. A small city on the north end of the largest of NY’s Finger Lakes, Geneva…

Geneva Light Opera’s production of Lehar’s The Merry Widow will feature prize-winning baritone Bryan Murray and soprano Alexis Olinyk in the superb acoustics of in the landmark Smith Opera House in Geneva, New York on July 25, 27, and 28. A small city on the north end of the largest of NY’s Finger Lakes, Geneva…

-

Topics: jake heggie, jamie barton, review

Latest on Parterre

Reach your audience through parterre box!

parterre box, “the most essential blog in opera” (New York Times), is now booking display and sponsored content advertising for the 2023-2024 season. Join Carnegie Hall, Lincoln Center, Warner Classics and many others in reaching your target audience through parterre box.

parterre box, “the most essential blog in opera” (New York Times), is now booking display and sponsored content advertising for the 2023-2024 season. Join Carnegie Hall, Lincoln Center, Warner Classics and many others in reaching your target audience through parterre box.

parterre in your box?

Get our free weekly newsletter delivered to your email.

Comments