The “embattled” San Francisco Symphony started the final leg of their 2023-24 Season with a whole month of concerts with their outgoing Music Director Esa-Pekka Salonen, beginning with a double-bill of Maurice Ravel’s Ma Mère l’Oye (Mother Goose), in collaboration with Alonzo King LINES Ballet, and Arnold Schoenberg’s Erwartung (Expectation), Opus 17, in its first San Francisco Symphony performances staged by esteemed director Peter Sellars, on Friday, June 7th (repeated on Saturday and Sunday matinee). “Embattled” is the keyword here, as up till now SF Symphony musicians are still trying to gather signatures for their petition to “urge the Board of Governors to do everything in their power to retain Esa-Pekka Salonen as Music Director and reverse planned cuts to programming, touring, and education.” Meanwhile, just last week, San Francisco Symphony Executive Director Matthew Spivey and Board President Priscilla Geeslin released an interview addressing the financial challenges and future plans.

The collaboration with Sellars, announced in 2022, was set to be a four-year adventure, staging four large-scale works. The journey was to commence with Igor Stravinsky’s Oedipus rex and Symphony of Psalms (in line with Salonen’s own farewell concert with Los Angeles Philharmonic in 2009) in 2022, followed by Kaija Saariaho’s Adriana Mater in 2023, Olivier Messiaen’s ambitious La Transfiguration de Notre Seigneur Jésus-Christ – one of his largest works – in 2024 and Leos Janácek’s tragicomedy The Cunning Little Vixen featuring Julia Bullock in the titular role in 2025. The first two indeed happened, and they were both well received. While I missed the first one, last year’s Adriana Mater was a truly unforgettable experience. However, reality unfortunately kicked in! In the current season, the Messiaen work was replaced by this double-bill, and sadly, no Vixen listed for the 2024-25 Season, either!

Despite all those troubles, I am happy to report that luckily, the music-making didn’t seem to be effected, as it remained at the highest level of excellence. But I’m getting ahead of myself…

Ravel originally wrote Ma Mère l’Oye in 1910 as a five-movement piano duet for Cyprian Godebski’s children (who were also the dedicatees). It bore the subtitle “cinq pièces enfantines” (five children’s pieces), and the movements were:

- Pavane de la Belle au bois dormant (Pavane of Sleeping Beauty)

- Petit Poucet (Little Tom Thumb / Hop-o’-My-Thumb)

- Laideronnette, impératrice des pagodes (Little Ugly Girl, Empress of the Pagodas)

- Les entretiens de la belle et de la bête (Conversation of Beauty and the Beast)

- Le jardin féerique (The Fairy Garden)

A year later, he orchestrated the piece into a suite, arguably the most frequently heard form in symphony halls today. Later that same year, Ravel expanded it into a full-blown ballet by adding interludes to separate the pieces, reordering them, and attaching two new movements, Prélude and Danse du rouet et scene (Spinning wheel dance and scene).

On the other hand, Schoenberg composed Erwartung in 1909, although it wasn’t premiered till 1924 in Prague. A one-act monodrama in four scenes, the libretto was written by aspiring poet and trainee medic Marie Pappenheim. The story revolves around The Woman, in an apprehensive state, looking for her husband at night in the forest. Jenny Judge, in the program notes, detailed that Pappenheim “wrote a disjointed and sometimes even ungrammatical monologue reminiscent of the speech of so-called “hysterics” undergoing the “talking cure. ‘Hysteria’ was an umbrella term used at the time to name what we would now consider a variety of psychological disorders: its symptoms ranged from extreme depression and anxiety, to hallucinations, paralysis, and loss of vision, hearing, and speech.”

The program notes offered a key to decode this pairing:

“Maurice Ravel’s Ma Mère l’Oye (Mother Goose) and Arnold Schoenberg’s Erwartung (Expectation) are very different works. One dances toward light, the other walks wide-eyed into darkness. One is suffused with a sense of enchantment and wonder, the other with grim foreboding. But there are deep similarities between the works, too – as befitting the fact that they were composed within a few years of each other. Both view the world from the perspective of a subject for whom reality and fantasy are indistinguishable. And there’s nothing sentimental about either of them.”

Alonzo King, the artistic director and choreographer for Alonzo King LINES Ballet, said his intention was “to unearth the deeper allegorical meanings beneath the fairytales and illustrate those with dance.” He further explained: “When I hear the sleeping princess, that’s a universal theme. And you know what it’s saying? All of us are in some somnambulistic state until we wake up. Inside us all, there is nobility. True nobility. But it’s deeply asleep – and it can only be woken up by love. And so, everybody is the sleeping princess.”

Seen in that philosophical lens, King’s choreography turned into a joyous self-exploration to find one’s true self. In addition, as the dance began and ended with the whole Company, it could also be interpreted as a community’s existential search. Dressed in various shades of earthy green-brown colors (costumes by Robert Rosenwasser), the Company began in a formation before breaking into multiple duos and trios and reassembling throughout the performance. The dancers moved into shapely geometrical forms that LINES Ballet was known for. Adji Cissoko and Shuaib Elhassan were particularly mesmerizing in their graceful duos for both “Pavane of Sleeping Beauty” and the subsequent “Conversation of Beauty and the Beast.” Luke Kritzeck’s soft lighting beautifully illuminated the stage, and he was definitely on board with the interpretative aspects of the performance; by the time the climax for “The Fairy Garden” arrived, the stage was impressively bathed with bright lights!

Relegated to the back of the stage (and in the dark), Salonen and the SF Symphony nonetheless provided a glorious reading of Ravel’s score, emphasizing the ethereal nature of the score. With great clarity from the orchestra and well-judged pacing, the score came alive in Salonen’s direction, so much so that there were times that I just closed my eyes and got swept away by the music! Salonen wasn’t afraid to dig deep into the darker points of the score (particularly the “Tom Thumb” section), and it paid significant dividends to the “bright lights” ending, both musically and interpretatively.

For Erwartung. Sellars offered his take on the interpretation:

“In our performances this weekend, we will be treating Schoenberg’s masterpiece as a lyrical love poem—as doubt, heartbreak, and hope against hope—rather than as a picture of disorientation. The piece moves through an immediate flood of contradictory emotions that follows the loss of a loved one (grief becoming rage, for example), and a gradual path towards acceptance, understanding, and revelation.”

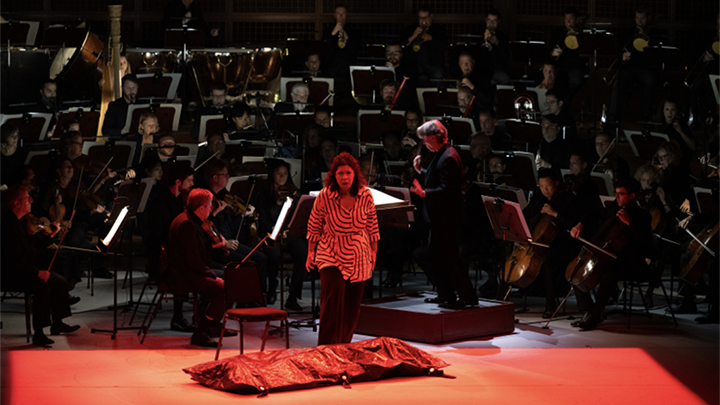

To be precise, Sellars framed this staging as “Accidental Death in Custody,” which was displayed on the screen before the performance, giving the audience the context of a body bag’s appearance on stage. The whole performance took place with just The Woman and the body bag in the “forest” of a room where two guards left her alone! It was a simple but effective interpretation, even if it lacked the sense of motion that the libretto seemed to suggest.

In this piece, Salonen and the SF Symphony had a formidable partner: soprano Mary Elizabeth Williams, whom I encountered as the Foreign Princess in last year’s Santa Fe’s Rusalka. I wasn’t prepared to be completely blown away by Williams’ artistry; not only did she write a whole article detailing her preparation for the role in the program notes, but she also translated the complete libretto! Specifically, she mentioned:

“What if the woman really is looking for her lover, and really does go into a dark and unknown place to find him? What if she finds his dead body in the very place where she hoped for a fulfilling reunion, and the shock of that experience causes her mind to run through the stages of grief at warp speed, as well as recapitulate their entire relationship and every meaningful moment that they had together? And what if the audience is there to witness this experience, as it happens, from a front-row seat inside her head?”

On stage, her understanding of the texts manifested in a compelling and intense performance, full of actions and nuances, as reflected by her movements and facial expressions. The body bag became her partner in crime as she held, hugged, hovered over, kicked, and cried over it. Seth Reiser’s lighting intensified this “morbid dance” by playing around with the color shifts.

Vocally, Williams was on point on Friday night; each phrase was delivered with various colors and emotions, and more importantly, it came from within. She was not just acting as The Woman; she fully embodied the role. While her top notes still bugged me a bit (less so than in Rusalka), Erwartung demonstrated her significantly round middle register. It was an extraordinary performance that was hard to look away from!

Salonen and the SF Symphony proved to be a perfect partner for Williams’ fire. Not to be outdone, Salonen upped the intensity in his leading the orchestra to bring all the orchestra colors of what Schoenberg called “emancipated dissonance,” the lack of an implied key. Nowhere than in this performance did that idea materialize, for the score ended with no resolution, just like The Woman finished with a body bag without any closure!

This was an outstanding achievement for everyone involved and a thrilling reminder of how far Salonen’s leadership had transformed the SF Symphony. Next weekend, he will bring out Dmitri Shostakovich’s Cello Concerto No. 1 with Sheku Kanneh-Mason, before traversing two great Austro-Germanic symphonies, Anton Bruckner’s Symphony No. 4 and Gustav Mahler’s Symphony No. 3 in the last two weekends of June.

The following day (June 8), I headed across the road to the War Memorial Opera House to experience the San Francisco Opera’s production of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s perennial classic Die Zauberflöte (The Magic Flute), which opened its Summer season on May 30th. By far the most performed German opera in the world, The Magic Flute’s tale of good versus evil continued to entertain audiences of all ages and will continue to do so in the future.

For this occasion, SF Opera decided to mount the widely popular Barrie Kosky and Suzanne Andrade’s “silent movie” production, which originated in Komische Oper Berlin in 2012 and has traveled to six continents (including the Middle East) and staged in more than 20 countries around the world. In the United States alone, the 12-year-old staging had been seen in 8 cities before these performances, starting from Los Angeles a year after its premiere. Additionally, the production had made multiple appearances on these pages, from Los Angeles (the 2016 and 2019 revivals), New York City in 2019 to Chicago in 2021.

Twelve years later, this staging still met with mixed reactions, especially from the critics, despite its popularity. There was no middle ground for this; people loved or loathed it. One thing is for sure: this production will appeal to you if you are a cinephile or a silent movie fan.

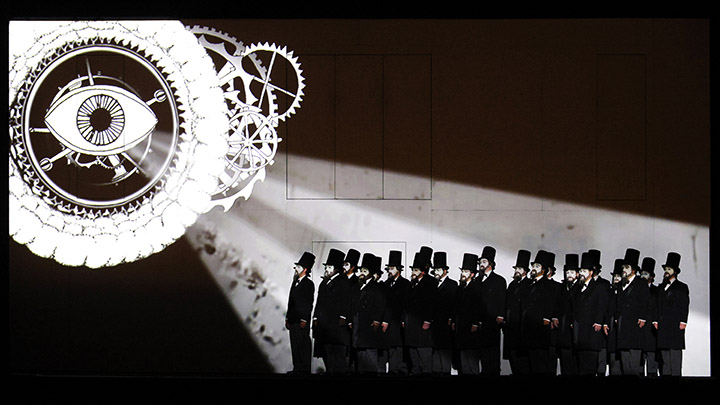

The gist of the production (and the source of the problems) could be described as follows: Inspired by silent movies from the 1920s, Kosky and Andrade (here it was revived by Tobias Ribitzki) decided to cut all the dialogue and replace it with intertitles with fortepiano accompaniment by Bryndon Hassman. The stage was practically just a gigantic white movie screen with over 700 animations (by Paul Barritt). The singers were strapped to multiple revolving doors all over that screen and illuminated at the right time and place. The animations were the story’s driving force, not the singers, so much so that they needed their own stage manager (Jennifer Harber). The singers sometimes perched so high up the screen that they were practically immobile. The singers, additionally, dressed like the characters of 1920s movies: Pamina resembling Louise Brooks (Pandora’s Box, 1929), Papageno as Buster Keaton (Sherlock Jr., 1924), and Monostatos as Max Schreck’s Count Orlok (Nosferatu, 1922).

My reaction was, well, mixed. The first time I saw this production (in Los Angeles during their first revival in 2016), I was blown away by the inventiveness of the animations and the smooth transitions of scenes and singers’ entrances and exits. Eight years later, I still immensely enjoyed the animations, but otherwise, I found parts of the production problematic. At the beginning of Act II, the part where the chorus members dressed like Abraham Lincoln (à la Sarastro) circled Pamina in her undergarments was disturbing. However, the biggest problem for me was the positioning of the singers, particularly those strapped on the ledges above, which affected their ability to sing perfectly.

Musically, there was a lot to recommend in this performance. Music Director Eun Sun Kim intentionally gave a big-band Mozart reading that sounded grand and dignified (my ears have been accustomed to HIP Mozart as of late). Still, she ensured that the orchestra didn’t cover the singers. The Chorus, led by John Keene, sang in unison whether on stage or in the multi-level towers on either side of the screen.

The cast for this show was mainly in good shape on Saturday. Many of them were making house debuts with these performances. Christina Gansch and debuting Lauri Vasar were the standouts as Pamina and Papageno. Gansch’s darker sound imbued the role with a degree of seriousness, particularly during “Ach, ich fühl’s.” With his many antics (including petting his cat), Vasar’s Papageno was the audience’s favorite, and his perfect comic timing and booming voice made his presence heard. His duet with the Papagena of Arianna Rodriguez was particularly memorable, especially with the backdrop visuals of multiple children in multiple rooms!

The Tamino, Amitai Pati, sang with conviction and elegance, although I wondered how he would be heard up above since his voice was very lyrical. On the other hand, Anna Siminska and Kwangchul Youn seemed to be the two most affected by the ledge placements on the screen. As The Queen of the Night, Siminska had a little problem with her coloratura in her two bravura pieces. Youn gave a dignified reading as Sarastro, although he, too, had issues with Sarastro’s lowest notes (which are really low!) All the comprimario roles were handled handsomely, from the three ladies of Olivia Smith, Ashley Dixon, and Maire Therese Carmack, the devilishly fun Monostatos from Zhengyi Bai (in Nosferatu costume!), the resounding voice of Jongwon Han’s Speaker, to the sweet sounds of the spirits of Niko Min, Solah Malik, and Jacob A. Rainow.

All in all, it was a fun night at the Opera, and the audience on Saturday applauded heartily all the performers. There wouldn’t be a livestream broadcast for this because of the animations. Nevertheless, five more performances remain, and you may want to consider going if you’re a big movie buff or appreciate the juxtaposition of animation and live theater. Purists, you’ve been warned!

Photos: San Francisco Symphony & Cory Weaver