Deserving as they are, much of the most consistently strong and innovative work comes from smaller companies that should be better known. For me, the memorably if quirkily named Idiopathic Ridiculopathy Consortium (IRC as it’s known locally) is at the top of that list.

The company, co-founded in 2006 by Producing Artistic Director and actor Tina Brock along with Bob Schmidt, has specialized in Absurdism, but not always in the way audiences might expect. Some classic examples of that genre feature prominently, including multiple productions of Ionesco’s The Bald Soprano and The Chairs.

But for my money, IRC’s work is most interesting—even revelatory—when Brock and company turn their absurdist interests to works that largely lie outside that category. The last four years have included exceptionally strong productions of plays as diverse as Christopher Durang’s Betty’s Summer Vacation, William Inge’s Come Back, Little Sheba, and Tennessee Williams’ Eccentricities of a Nightingale.

Another Williams’ rarity is on tap now for their return to live theater—The Two Character Play—and IRC’s interest in absurdism is an especially apt lens here.

As with so much later Williams, the piece has a checkered and rather bleak history. It premiered in London in 1967 and, reworked and retitled as Out Cry, made its way to Broadway—very briefly—in March 1973. A 2013 off-Broadway revival, again called The Two Character Play, fared rather better, though the behind-the-scenes antics of star Amanda Plummer threatened to overshadow the show itself.

I should say that in all versions I know, the core idea is the same: Felice and Clare are brother and sister, both presumably actors, and both mysteriously abandoned in a theater somewhere and sometime in the midst of a tour.

“Presumably” is a key word here. Again, as is so often the case with later Williams’ work, audiences will be better off if they check their desire for narrative coherence and conventional logic at the door.

To start with, there is Williams’ The Two Character Play—and the play-within-a-play that Felice and Clare are performing—which is also called “ The Two Character Play.” Are they separate? Intersecting? All one entity? After seeing and reading it at least a couple of time, I still couldn’t tell you. It’s one of many tantalizing ambiguities that prove stubbornly resistant to analysis.

To their credit, the IRC production (which lists “The Company and Peggy Meacham” as directors) is content to let the audience wonder. Their approach instead is to steep us in a world that hauntingly blends backstage, onstage and the grim but mysteriously vague history that led to what we are watching.

Parts of the stage design by Dirk Durosette evoke a homey if slightly faded parlor from perhaps the 1920s—but look above it and you’ll see a kind of doll house suspended in the air. Off to the side sits a scaffold that looks like just what a contemporary designer would work on to install a set.

Cheerful technicolor scrims painted with sunflowers seem to appear and disappear before our eyes. Costumes by Millie Hiibel, Lighting by Shannon Zura, and sound by Christopher Colucci reinforce the ghostly but gripping sense of Felice and Clare’s “reality.”

It’s an appropriately destabilizing world to lead us into the play’s heart—a conversation between brother and sister that is permeated by the specter of family violence. We don’t know exactly what happened—and likely, Felice and Clare wouldn’t agree on that point—but it’s clearly been emotionally crippling.

The two seem condemned to live within this conversation while they are physically stuck inside the theater. For both, the very idea of the outside world is desired, feared, and ultimately unattainable.

It is in many ways a difficult work—funny, heartbreaking, but difficult. Yet Williams’ own devotion to The Two Character Play—he called it “the very heart of my life,” and continued to work on it for years—opens the door for us.

Siblings Felice and Clare almost certainly stand in for Williams himself and his adored sister Rose, who in her early 20s was subjected to a prefrontal lobotomy, and was institutionalized for the rest of her long life. The reasons for the surgery remain cloudy—suggestions of schizophrenia are noted, but her catalogue of symptoms is difficult to categorize, and many accounts of her behavior suggest that she was also a bit of hellion.

What clearly emerges is that Rose was a source of deep embarrassment to her parents—and that Tennessee never forgave himself for failing to “save” her. After the surgery, he, and later his estate, paid for her care; Rose would outlive Tennessee by 13 years.

It’s universally understood that Rose served as the model for Laura in The Glass Menagerie, and most of us “know” her through this loving but domesticated and sentimentalized portrait. Astute audiences, though, might take note of Williams’ warning at the very beginning that we should not entirely trust his “memory play,” as he packs “truth in the pleasant disguise of illusion.”

The true revelation of IRC’s The Two Character Play is to so vividly connect Felice and Clare to Tennessee and Rose, and to provide a sense of that relationship which deeply enriches our understanding of the playwrights more familiar works.

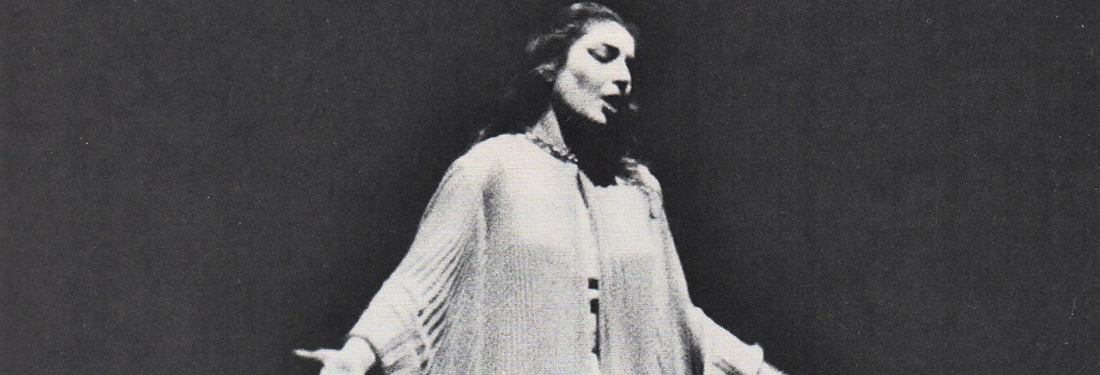

The two actors here give brilliant, unflinching performances that tie us to their real-life counterparts as I’ve never seen before. John Zak (Felice) uncannily distills the Williams’ louche, shopworn sense of Southern grandeur.

Even more astonishing is Tina Brock’s Clare—and the resulting, illuminated-by-lightning sense of Rose Williams in all her complexity. By turns crude and coquettish, fierce and fragile, brilliantly funny and soul-crushingly tragic—Brock is simply unforgettable.

This is a show to make the trip from New York to see. Among many other virtues, it provides invaluable insights into the more familiar canon of America’s greatest playwright.

Photos by Johanna Austin

Comments