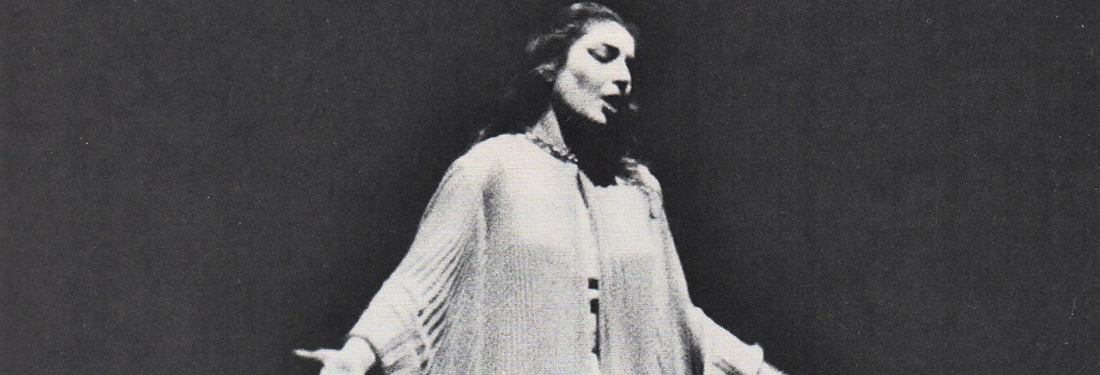

David Fox: I remember that evening so well! I saw it opening night—in fact, I’d been the pre-opera speaker for that, though I had not seen any rehearsals, nor did I know much about Lisette Oropesa beyond her name. If I’d heard her, it was as Woglinde in Rheingold, which of course is quite a different challenge. Anyway, I recall that from the very first minutes, I felt a kind of electricity that suggested something of international stature was happening—across the board, but in her performance especially. As we both know, much is often made by aficionados of the kind of steeplechase nature of Violetta—the coloratura, lyric, and dramatic soprano aspects of the vocal writing, and of course the acting challenges as well. I sometimes think we over-fetishize this role in particular, but the fact is it’s rare for any soprano to fully embrace all aspects. And that’s what happened here. In passage after passage, Oropesa had full mastery of every part of it. I noticed it even in the Brindisi, where every turn simply sparkled. And it built from there. Honestly, when you suggested we write about it, I was both excited and reluctant. I hadn’t watched the video because I didn’t want to discover I’d over-praised her performance. But indeed, it looks as great as I remembered.

CK: I held off on revisiting it for several months too, for the exact same reason. What I vividly recall from attending this production in-house—at least at the beginning—was a rather blasé feeling that, after Opera Philadelphia had delivered so many exciting and challenging new works in quick succession, one more Traviata seemed so been there, done that. Needless to say, that attitude receded almost instantly. First of all, the production (staged by Paul Curran) is no repertory warhorse; it’s sleek and attractive, with sets and costumes that suggest an update to the mid-twentieth century, and some interesting ideas about the work’s social context. Barone Douphol for example, played here with noticeable malevolence by Daniel Mobbs, shows up at Flora’s party in what looks like a stark military uniform—does this production take place in an authoritarian society?

DF: The military overtones are indeed intriguing here, but I recall thinking even at the time that the whole look and feel exudes a 1950s glamour that I associate with two favorite filmmakers: Douglas Sirk and Alfred Hitchcock. That was even more striking watching it on video—the beige-and-gold of Violetta’s home in Act II is a particularly Hitchockian palette! And it absolutely works for Traviata.

CK: But most of all, Oropesa exudes a sense of intelligence and grace that makes it hard to fathom this as a first traversal. Everything is so put together, and you sense that even in moments that don’t sit with perfect comfort in her voice and manner, that she’s worked things through and created something seamless.

DF: God is in the details, as they say—and for me, in passage after passage, Oropesa realized those details as few singers have in my experience. The short internal trills in “Sempre libera,” for example—often they are just brushed over, but here they were not only perfectly voiced, but also made dramatic sense. She has a kind of natural grace with the line that I think really can’t be taught—you either make music in your singing or you don’t, and she absolutely does. I would say that for her the challenges were in the big dramatic outbursts—”Amami, Alfredo” would be one example—which are a stretch for her lyric resources. But by scaling everything so precisely, she could effectively suggest real grandeur. To me, that’s true artistry.

CK: Some moments in the long exchange between Violetta and Giorgio Germont seemed to tax Oropesa, but she always remained dramatically committed. And even moments that didn’t sit entirely well were forgotten when she approached a section of music that felt, if you’ll forgive an overused expression, like they had been written for her. One such example would be “Dite alla giovine,” and I’d have to stretch pretty far back in my memory to recall an equal either musically or dramatically. Oropesa spins the moment out on the tiniest thread of voice, with conductor Corrado Rovaris keeping the orchestra equally hushed, and Violetta’s steadfast sense of sacrifice becomes overwhelmingly moving. You feel no premeditation—instead, it clicks in the moment that, out of duty and honor, this woman is letting her final chance at contentment slip through her fingers. I cried in the theater and I cried in my living room, which are probably the only two times I’ve been genuinely moved to tears by this opera.

DF: “Dite alla giovine” is one of my test moments in Traviata; another similar one is Violetta’s entrance into the Act II / Scene II ensemble, “Alfredo, Alfredo, di questo core.” I got shivers here from both, as well as the end of “Addio del passato,” which seemed to stop time. What I remember from opening night is being pleased that the audience as a whole seemed to really get how special these moments were from Oropesa. The applause at the “Sempre libera” E flat was wildly enthusiastic—but the reception at the end of the confrontation with Germont seemed even more enrapt, as well it should have! You mentioned Rovaris, and I want to agree—he had a lot to do with Oropesa’s success, but going far beyond it—this is one of the most cohesive and compellingly conducted performances I’ve ever heard, and his occasionally surprisingly brisk tempi—the Brindisi, for example—I found entirely convincing.

CK: I do think in this performance you can grasp the benefits of smaller companies approaching these familiar works with less expectation than, say, at the Met or Covent Garden, where there is probably more of a received notion of how a performance should go. Looking at my notes, I found myself classifying moments as “thrilling” and “surprising,” which are words I wouldn’t necessarily associate with a work I know so well. I felt similarly about Opera Philadelphia’s La Boheme in 2019.

DF: And, of course, a successful Traviata needs more than a great Violetta and fine conducting. It needs a shared theatrical vision, among other things, which it truly gets here. You mentioned Daniel Mobbs as a standout in a small role—others who were noticeable were Jarrett Ott as the Marchese, and Katherine Pracht as Flora. But of course, it’s Alfredo and Germont who are extremely important here, and I think both are very well handled. Alek Shrader is the essence of Alfredo in his presence and acting—handsome, privileged, well-meaning but naive. His lyric tenor here feels a bit restricted as the very top, but he’s excellent and scrupulously musical in most of it.

CK: Shrader and Oropesa were both in their early thirties at the time, and I sensed more than ever how young Alfredo and Violetta really are. It amplifies the passion, the anger, and ultimately, the pain of the loss.

DF: I’m interested that you mention their youth. I had just watched Greta Garbo‘s Camille, where the dynamic is quite different—she seems so much older and more worldly than Robert Taylor, her lover. But here, the combined youth is even more poignant. Anyway, I also want to single out Stephen Powell as a vividly theatrical Germont. Powell starts off a bit below best form (probably just an off-night—a few months before, he was absolutely sensational in La Favorite at Caramoor). But he warms up and delivers the aria and even its oft-derided cabaletta with elegance and power.

CK: Yes, Powell’s singing is coarser than I remembered—a surprise, since I usually regard him as one of America’s best (and most criminally underutilized) Verdi baritones—but his acting is superb throughout. This is no gruff caricature Germont pere; he’s a caring father, and he truly makes you believe that he feels warmly, even paternally, toward Violetta.

DF: Cameron, you started this off by pointing out that when Opera Philadelphia staged this Traviata, it was in the midst of quite a bit of less familiar kinds of work. I went back to look at the whole season of 2015-16, which was a truly extraordinary one. Under David Devan‘s leadership, it began with the wildly imaginative Andy: A Popera; included a superb Capriccio that was done by Curtis Opera forces; and ended with Lawrence Brownlee in Yardbird. That would be a remarkable series of achievements by any company, I think. Looking it over made me tear up, longing for the moment they can take to the physical stage again. Soon, I hope—soon!

CK: Hear, hear! In the meantime, though, I would encourage anyone who hasn’t done so already to subscribe to the Opera Philadelphia Channel. One of the rare bright sides of the pandemic pause, for me, has been the opportunity to familiarize myself with the works of smaller companies around the country who I might not get to under normal circumstances. Hopefully, those who know Opera Philadelphia by reputation alone will get the chance to see for themselves what us locals have been trumpeting for years.

Photo by Kelly & Massa

Comments