Wikipedia lists 75 Orphic operas. And Reinhard Kapp has a 100-page chronology of them.

There’s Jacopo Peri’s Euridice, the first surviving opera, from 1600. Claudio Monteverdi’s Orfeo, considered the first operatic masterpiece, from 1607. And most recently, there’s Matthew Aucoin’s Eurydice, which the Met put on in 2021.

Somewhere in the middle, there’s Christoph Willibald Gluck’s Orfeo ed Euridice, from 1762, which is running at the Metropolitan Opera through June 8. Gluck’s is the most performed Orphic opera, partly because it’s only 90 minutes long.

Why this Orpheus obsession? He is, after all, is the “first musician.” But Aucoin also proposes, in his book The Impossible Art, that composers have been drawn to the impossibility of bringing someone back from the dead — comparing it to the mammoth task of mounting an opera.

This season’s Orfeo is sung by countertenor Anthony Roth Costanzo — who is having something of a moment, being recently named the artistic director of Opera Philadelphia, and presenting his “Myths” series across boroughs.

On opening night, Costanzo had no trouble being heard, with clarion high notes, as the “echo,” in his act-one aria, as well as a welcome huskiness in his lower register.

Originally written for a castrato (and revised in 1774 for haut-contre to suit Parisian tastes), the role is, today, performed by either a countertenor, or mezzo-soprano en travesti. The last time this Mark Morris production graced the Met’s stage, Orfeo was sung by mezzo Jamie Barton in drag makeup.

Whether mezzo or countertenor, however, there’s something queer about this Orfeo. Let’s not forget that, in Ovid‘s version of the myth, Orpheus consoles himself after Eurydice’s (second) death in the arms of some Thracian boys, having “fled completely from the love of women.”

Costanzo is known to bring this viewpoint to his roles — such as in Philip Glass’s Akhnaten— which comes naturally with having a voice type “at odds” with his appearance. But this “queer reading” is subtler. This isn’t a case of the obviously gay student cast as the heartthrob lead in the school musical.

Orfeo’s love for Euridice, sung by soprano Ying Fang, is believable. Maybe even queer? (Though he’s clearly in love with himself, too.) Perhaps it’s because, when Fang finally appears in the third act, she is positively glowing — with a gorgeous, buttercream voice.

It doesn’t hurt, in terms of a “queer reading,” that this production, which debuted in 2007, features costumes by Isaac Mizrahi alongside Morris’s campy choreography.

The dancers, wearing color-coded spring linens — grey in the first act, white in the second, pastels in the third — reminded me a bit too much of Mizrahi’s early aughts Target collection.

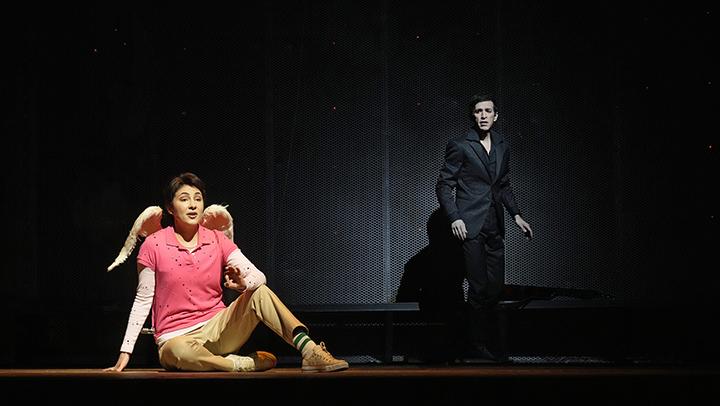

The worst costume, though, was for Amore, sung by puckish soprano Elena Villalón. In a pink polo and khakis, she was lowered from the ceiling like Peter Pan. It felt almost lesbo-phobic.

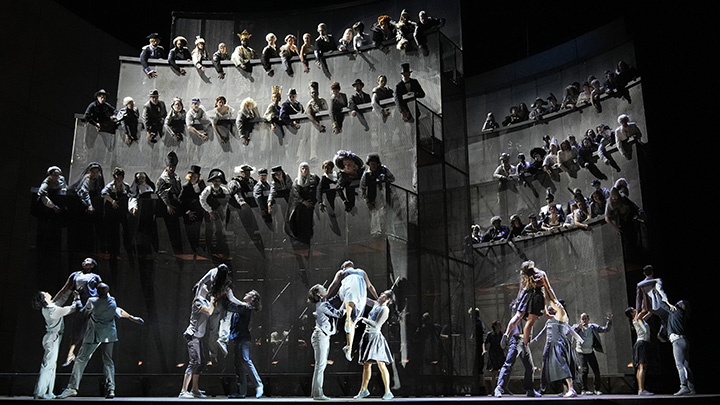

In the second act, the chorus — dressed as long-dead historical personages such as Einstein, Abe Lincoln, Marie Antoinette, and Jesus — sing “Chi mai dell’ Erebo” from brutalist stadium seats. The Furies dance, zombie-like, swatting themselves, as if attacked by mosquitos.

The sad-boy Orfeo, forgoing the lyre for a guitar (played in the orchestra by a harp), pleads to be let through the gates of Hades: “Mille pene, ombre sdegnose, come voi sopporto anch’io.” (“My own hell I carry in me, blazing deep in my heart.”)

Surrounded by sparkling stalactites, the lovers are reunited. Euridice is characterized as a feminist, suspecting infidelity. Reversing gendered stereotypes, Orfeo is the irrational and impulsive one.

In duet, Costanzo’s and Fang’s ranges are touching distance (even though they can’t look at each other). And when Costanzo chokingly sings “Che farò senza Euridice?” it’s heartbreaking, despite the major key.

Unlike the Greek myth, Gluck’s Orfeo ed Euridice has a happy ending. (This is because it was written for a joyous occasion: Emperor Francis I’s name-day celebrations.)

When Euridice is revived (again) by Amore, it feels almost too easy. As Morris’s dancers cavort, in couples and throuples, making heart shapes with their arms, the chorus sings, “Trionfi Amore!” Love wins.

Photos: Ken Howard

Comments