There is something incredibly audacious about Matthew Aucoin’s Eurydice—which opened at the Met on Tuesday night, having premiered at LA Opera last year. By adding a new voice to this impressive lineage, the opera’s very existence asserts that there is some part of this story that still needs to be told, some angle left unexplored, something substantial left to say.

The basis for Aucoin’s opera is the critically acclaimed 2003 play by Sarah Ruhl. In Ruhl’s play, Eurydice is a retiring bookworm who, frustrated that Orpheus values his music over her, would rather stay in the underworld with her dead father than return to earth with her husband.

This is a certainly a clever take on the myth. And, in the play (which, admittedly, I have only read), it works wonderfully. Ruhl’s work hinges on the contrast between Orpheus’s effortless and charismatic musicality and Eurydice’s awkward bookishness.

This Capriccio-esque struggle between words and music is established at the play’s outset and culminates, at the moment Eurydice sabotages her husband’s attempt to extract her from the underworld, in Orpheus chiding his dead wife for her lack of musicianship.

In the play, Eurydice, who can’t sing and can’t keep in time, comes across as a more introverted, more self-reflective version of Dot from Sunday in the Park with George, constantly disillusioned with the creative self-absorption of her significant other. At one point, after Orpheus asks her to clap the beat of a melody, Eurydice snaps at him: “I don’t need to know about rhythm. I have my books.”

This, the beating heart of Ruhl’s play, was almost entirely cut from Aucoin’s opera. And, to some extent, I can understand why. Eurydice can’t be a bad singer. It is an opera, after all. Suspension of disbelief can only go so far in convincing me that Erin Morley—who sang the title role so beautifully on Tuesday night—can’t sing.

But here is the central problem with Aucoin’s opera: without the core conflict between Orpheus and Eurydice, the opera’s plot could be a tad vexing. Crucially, it was often unclear why Morley’s Eurydice didn’t want to return to the living world with Orpheus (Joshua Hopkins).

For example, as shorthand for Orpheus’s self-centeredness, Aucoin gives the character a bare-chested, angel-winged body double (Jakub Józef Orlinski, making his Met debut), whom he embraces and caresses throughout the opera. But all of this just amounted to more obfuscation, more abstraction, and did little to elucidate either Orpheus’s or Eurydice’s motivations throughout the opera.

Moreover, I found it almost impossible to hear Orlinski’s delicate countertenor over Hopkins’s stentorian baritone, leaving me wondering whether this elaborate Verfremdungseffekt served any purpose at all.

Aucoin keeps some of the most high-concept aspects of the source material. But, out of context, these plot points can seem arbitrary, conceited, and even confusing. In Ruhl’s play, when the dead enter the underworld, they not only lose all memory, but also lose all human literacy, unable to speak, read, or write in human language (they speak, instead, in the dead language—the language of the stones).

Aucoin keeps this facet of Ruhl’s work. But it loses all significance in Aucoin’s opera because he never establishes the significance of the written word to Eurydice’s character. When Eurydice loses the ability to read in the opera, it is an emotionally empty event with uncertain dramatic ramifications.

In Ruhl’s play, Eurydice’s father reteaches her language by reading to her from the complete works of William Shakespeare, an act of care that galvanizes Eurydice’s decision to remain in the underworld. When this same scene happens in the opera, it is almost meaningless, mainly because the audience doesn’t know how much the simple act of reading means to Eurydice. We don’t grasp the scene’s full emotional significance. It’s just a guy, onstage, reading from King Lear.

What’s more, it is often unclear what language the characters are supposed to be singing in at any given time. When characters are supposed to have lost the power of human language, they continue to sing (very eloquently) in English (occasionally forgetting the odd word). Thus, it was difficult to tell whether a character was speaking in a human language or the “language of the stones” at any given point in time.

This dramatic ploy might work well in the spoken theater, where it is generally much easier to follow such belletristic devices. But in opera—where we are already asked to suspend disbelief over the fact that the characters sing all the time—this just made for an added layer of mystification. (It was made all the more confusing by the fact that Orpheus must sing in Latin in order to communicate with the dead—a scene that is not in the play.)

All this leads me to the conclusion: No, we don’t really need another “Orpheus” opera.

Or, rather, we don’t need this one.

Ruhl’s play is a poor subject for an opera precisely because it is about the contrast between the musical and the unmusical. Setting it to music did little but muddy the otherwise lucid source material.

Compared to Fire Shut Up in My Bones (which the Met premiered earlier this season), it feels dated, like the last, rattling gasp of a dying Orphic tradition. Fire Shut Up in My Bones felt fresh, urgent, emotionally immediate—a story that needed to be told today and needed to be told on the operatic stage. Eurydice never quite justified its own existence in the same way.

All this is a shame because the performance, the production, and the score itself were all so utterly compelling.

In Eurydice, the Met offered a slick operatic product, proving (as they did with Fire earlier this season) that when they do contemporary opera, they do it really, really well.

Aucoin’s score was an absolute delight. It was clear that this was a composer who knows how to write opera. Indeed, at the age of just 31, Aucoin already has five operas under his belt—an impressive feat for a composer of any age. And his firm grasp of the artform shone through in every level of his setting.

Vocal lines found the perfect balance between the melodic and dramatic, the grotesque and the arioso, the straightforward and the virtuosic. He struck a cool equilibrium between clearly delivering the text and animating it with musical and vocal color.

The score was impeccably paced. Aucoin’s musical language is eclectic, equal parts John Adams, Mark Anthony Turnage and Kaija Saariaho. He also doesn’t shy away from musical pastiche: Burt Bacharach-style lounge music, new-wave techno-pop, Gregorian chant, Lullian baroque opera were all parodied. Did I catch a quote from Turn of the Screw in there too?

This kaleidoscopic musical array comes at you hard and fast, hitting you in an overwhelming, exhilarating rush. There’s no time to get bored: by the time you’ve processed one of Aucoin’s musical delights, he’s already swept you up in the next idea, already engulfed you in the next wave of sound.

Aucoin’s score has grandeur to it: there are big musical set pieces (arias, duets, interludes, choruses, etc.); the orchestration is rich and vibrant; musical effects are painted in bright, dazzling colors; dramatic moments are underscored with bold, Wagnerian orchestral eruptions. It is an opera tailor-made for a house the size of the Met.

Yet, within this grandeur, Aucoin had a knack for capturing mood and humor. As much as I found the adaptation of the libretto to be confusing and dissatisfying, lyrics were often set in a way that brought out the wry irony of Ruhl’s text. This could be a disarming effect when set against the sheer creepiness of Aucoin’s operatic underworld, with its rasping orchestral shrieks, writhing dissonances, haunting offstage chorales, and eerie percussive scratchings.

Mary Zimmerman’s production offered a barer, more restrained canvas on which all this musical activity was projected. Zimmerman populated Daniel Ostling’s mostly bare scenery with sundry, well-placed, minimalistic touches, representing the opera’s various settings: a moon (glowing white in the world of the living and black in the underworld), a field of wheat, a stone palisade, a shower cubicle, an elevator shaft, a few deck chairs, a white staircase.

Yet these lonely set-pieces had a significant impact on the Met stage, giving plenty of space for Aucoin’s busy, feverish score to breathe and grounding the (often confusing) onstage action.

Zimmerman’s production seemed designed to draw focus onto the voices. Singers were always placed front and center, as if singing directly to the audience. And their costumes (by Ana Kuzmanic) were often the brightest, boldest, zaniest objects onstage, pulling the eye towards them.

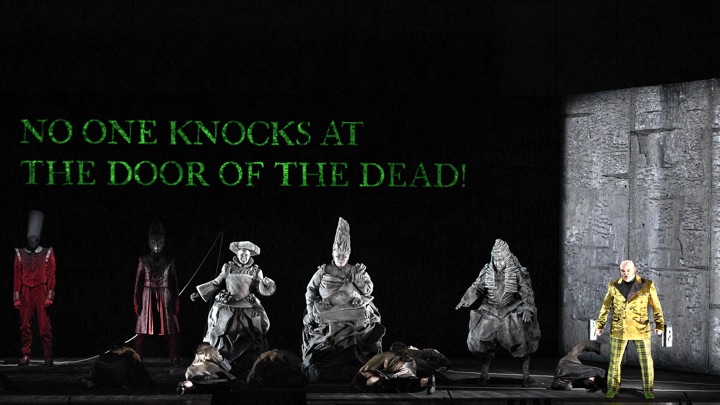

Eurydice spent much of the opera in a wedding dress, covered by a violet swing coat with matching fascinator; Hades appeared on stilts, in a long green dressing gown, big pointy devil horns, and a long spiky tail; the three Stones (the bureaucratic guardians of the underworld in Aucoin’s opera) wore grey, crumpled, stiffened, vaguely 17th-century livery.

The singing, on the whole, was top-notch. Morley’s Eurydice was often difficult to hear, especially in the lower register: the lighter parts of her voice were no match for the full weight and vigor of Aucoin’s orchestration. But, that being said, she found thoughtful, scintillating ways of shaping Aucoin’s vocal phrases, claiming a musicality in the vocal line that was distinctly her own.

In Eurydice’s big second-act aria (a lengthy plaint on the difficulties of loving an artist), Morley revealed an elegant silvery tone, weaving gentle sonic tendrils above softly pulsating chords. Her other big moment in Act II—a monologue with offstage chorus in which Eurydice recounts her journey to the underworld—allowed Morley to flex her dramatic chops.

Aucoin sets this scene in spiky, angular, phrases, punctured but strange orchestral surges; and yet Morley found a cool effortlessness in the vocal line, holding her resolve against the roiling textures of Aucoin’s underworld (even as she was lifted aloft by a troupe of shades).

Hopkins’s Orpheus was not the enchanting, sweet-voiced balladeer that we’ve come to expect from other “Orpheus” operas, but a strident, commanding vocal presence. With metallic cut and princely luster, Hopkins’s voice left the distinct impression that Orpheus’s musical powers would be better attributed to his sheer vocal force than to the affective power of his song.

Nathan Berg’s solemn turn as Eurydice’s father was earnest, if a little gruff. An extended letter-writing aria in Act I was delivered in a blunt, steely sprechstimme—full of raw emotion but perhaps lacking in lyricism. Berg seemed to thaw into the role over the course of the opera, finding tenderness and warmth in his vocal lines—especially when singing alongside Morley.

The vocal highlight, for me, was Barry Banks’s sneering, jeering, campy Hades. In Ruhl’s play, Hades is a child on a tricycle (he hopes his marriage to Eurydice will “make him a man”). In the opera, however, he’s more of a Hugh Hefner-type figure, and Banks played him with as much sleaze and cheese as possible.

Aucoin sets the role in an extremely high tessitura and Banks relished every screeching high note, piling on buckets of oily, charaktertenor squillo. His three sidekicks, the Stones (Ronnita Miller, Stacey Tappan, and Chad Shelton), served as Greek chorus—a tight vocal trio all round, especially when “mickeymoused” by the orchestral brass.

But the real star of the show was the Met Opera Orchestra, conducted on Tuesday by Yannick Nézet-Séguin. Aucoin tasks the orchestra with a number of unconventional effects, from microtonal slides, to hand-clapping, and chain-rattling. The Met Orchestra took on these challenges with undeniable verve, producing a sound that had all the richness of grand opera with all the precision and clarity of a chamber ensemble.

It is a testament to Nézet-Séguin’s commitment to fostering contemporary opera at the Met that some of his best conducting should appear in new works: with Eurydice on Tuesday and Fire Shut Up in My Bones earlier this season, the music director has shown that the Met Orchestra sounds just as (if not more) accomplished in contemporary works as it does in the tried-and-true classics.

For all Eurydice’s shortcomings, the opera is worth seeing simply to hear the orchestra take on this towering score with such brio. After all, we’ve followed Orpheus into the underworld countless times before. What’s another trip down below?

Photo: Marty Sohl / Met Opera

Comments