Those who know me well know how much I love sinking into the glittery morass of Zandonai and D’Annunzio’s Francesca da Rimini. It’s probably the opera that sits closest to my heart and for a period in high school, the famous cello solo that underscores Paolo and Francesca’s first meeting was my alarm clock sound.

In the interest of avoiding too much of a good thing, it’s a work I don’t often seek out, but I found myself listening to the Act III duet on the occasion of Leyla Gencer’s birthday yesterday and I was taken once again – not necessarily by the score, which I practically know by heart, but by the ease and seamlessness with which it flowed out of Gencer and Renato Cioni. Gencer is probably not the first that comes to mind when you think of clean, scrupulously musical singers, but here, in her 1961 prime, the singing has a rippling lucidity to it and her legendary glottis remains in surprisingly consistent check. Meanwhile, a friend of mine once referred to that cadre of B-tier midcentury Italian tenors that flanked more famous prima donnas as “ogres,” and in many cases (I’m looking at you, Francesco Albanese), he was right. But even if the high notes may turn leathery, Cioni’s firmly parsed, blonde instrument is well above swamp quality. She sobs and swoons with a level of taste that nowadays seems surprising and he meets her and ups the ante.

Francesca da Rimini, both by virtue of its subject matter and its chronology, sits on the outskirts of the temporal distinction of “verismo.” (A distinction, it should be said, that has no settled definition or time period amongst Italian musicologists.) It’s also now a label that feeds its own marginalization since it became synonymous for all sorts of deviant characters’ excusing singers’ vocal “bad behavior.” “Verismo,” per the received knowledge, must grunt, grumble, or shriek to drag its real as close as possible to ours. But I count myself as a card-carrying member of its garlicky fan club and that is why I was especially dismayed to encounter this year’s album by Saioa Hernandez, Verismo d’Oro on the Euroarts label, which I ill-advisedly sought on the heels of Gencer and Cioni’s Act III love duet. (The album includes Francesca’s final monologue, rather than the more popular first one.)

Now, I won’t attempt a review of the whole album – truth be told, I’d rather not even listen to the entire thing – but I do think something about this album deserves comment. Hernandez, whom I found enjoyable enough in her Sant’Ambrogio debut as Odabella back in 2018, works steadily in Europe. With the recent addition of Turandot, in which critic Roberto Mori praised her vocal range but described her portrayal as “sculptural, perhaps monolithic, more inclined to verista outbursts than reservation or to analytical phrasing,” she now sings every major verismo diva role and then some.

It’s easy to see why people are drawn to this voice, which is warm and rounded with an ample middle and a chest register that doesn’t quit. Of her more prominent peers on the Italian circuit — Maria Jose Siri is riveting onstage but her voice is an absolute mess whereas Chiara Isotton has the opposite problem – she’s the most surefooted interpreter. She’s also savvy on social media and, perhaps most importantly, has an endorsement from Placido Domingo, to the extent that that means anything anymore. But it’s a flabby instrument that skates by on vibes rather than insight and the effects spring from the text with the same naturalness with which blonde hair springs from her head.

The album, or at least what I listened to of it, catches her at highs and lows in roles that she is largely not performing these days (Iris & Isabeau, Alfano’s Sakuntalà, Giordano’s Marcella). The duet from Il tabarro finds her at an undisciplined best, while “Poveri fiori” from Adriana Lecouvreur is so shrieky, messy, and free of style or phrasing that I can’t imagine what earlier takes, if there were any, must have sounded like. But she’s not cord-shreddingly bad and instead sort of anonymously troops through the selections ejaculating “emotion” through imperiousness and syrupy tone. The aria from Marcella, an opera I had simply never heard of, is so textually unclear it might as well be a vocalise. (On the other hand, though, what should one expect from someone whose name is 80% vowels?).

But believe it or not, I didn’t come here to write a pan of Hernandez, who has some gifts, an obvious and admirable curiosity, and seems like a reliable colleague. In fact, I still struggle to pinpoint exactly what incited me about this album, something that surely goes beyond this one performer. Maybe it’s just that “verismo” has become something of a dog-whistle word for me, given that the propensity to slap it on any Italian opera written 1870 and 1924 gravely simplifies how these works engage everything from racial politics to performance practice. Or maybe it’s my personal resistance to embracing a filth/dementia dialectic like some of the armchair critics who raised me. Because to call something “filth” – and I will concede that this album checks many if not most of those boxes – implies that there exists a better alternative whereas Hernandez’s histrionic corner of the repertoire is, at the highest levels, championed more or less by her alone. Call it my fatalistic Gen Z snowflake tendencies, but I can’t see this as a giddy gay party record schlock campfest rather than just a bummer, I guess in part for her but mostly for this repertoire that is done a disservice by careless, ungainly singing. To the extent that singers should be considered stewards of the music they sing, equating bad singing to whatever “verismo” is will only be to the detriment of verismo. And that negligence suffuses and sinks this album.

But just as there have always been disappointing singers, there are certainly contemporary singers making this repertoire meaningful. Ermonela Jaho lifts this music high with a less stereotypically and stereophonically voluptuous sound and Carmen Giannatasio crossed over from bel canto to become quite a multifaceted verista. Hernandez’s approach, however, seems to be ill gotten inheritance of the later Callas pretenders and that is an unfortunate thing. For around the same time that early music charged into the material realities of its nascent era with the midcentury historical performance movement, “verismo” undermined a more versatile vocal technique to shove singing closer and closer to our emotional and verbal realities. We all simultaneously sought authenticity, but cleaved along the lines of practice versus sentiment, gut versus gutsy. The best artists, we know, assimilate these things and make them their own no matter the era of the score. But I can’t help but feel like verismo à la Hernandez is not going to help anybody discover anything other than the “stop” button on their streaming service or CD player.

The success of the NY-based Teatro Nuovo and the recent establishment of a Dresden-based Richard Wagner Academy are the clearest evidence yet that the historically informed performance movement is creeping closer to the Italian operas that both constitute the bulk of the standard repertoire and were themselves born around the advent of recording technology. And with the recent designation of “canto lirico Italiano” as a UNESCO world heritage quantity, it’s not unfeasible that Italy’s far-right government might eventually take interest anew in Italy’s melodic tradition like previous regimes did.

While I’m doubtful that we will start seeing productions of Iris sprout up across the peninsula any time soon, the advent of historically informed “verismo” may be nearer than we think. And if that’s the case, then what are we to look to these works for, given that many of them are too familiar already? Hernandez’s album, much less those who might buy it, can provide no answer. On the other hand, neither can dusting off the records of the Queen of the Pirates and retreating to the living room. At the end of the day, neither are fulfilling options and authenticity is a false god. But I believe that the essential, vital qualities of opera exist, too, in these outré texts. It will just take thought – a lot more of it –to find them.

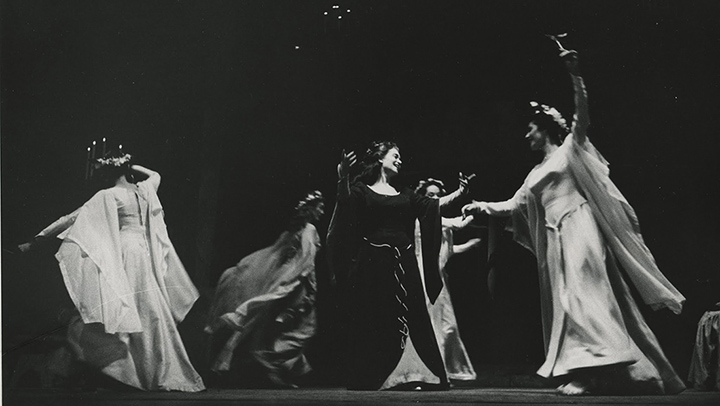

Photo: Robert Lackenbach