Le nozze di Figaro, which came in 2019-2020 season, was set in the late 18th century post-colonial America where the Nation was just founded, and hope and optimism were abound. After a long delay because of Covid-19, the second chapter, surprisingly non-consecutive Così fan tutte) appeared last November to represent the characters at moral crossroads in the late 1930s.

For the conclusion, Cavanagh said the following in his Director’s Note:

Now we find ourselves in a time of finality and conclusion, when the consequences of those selfish actions have been visited on this same place, some 150 years later. It is the late 2080s, a not-too-distant and not unlikely future in a now-ruined world, destroyed not by some external force but a natural one, that of human nature at its worst. Greed, desire, and hunger for power, without regard for the impacts on our fellow human beings, has stolen our future and loosed monsters on the world. And those monsters look like us.

Before the curtain opened, I kind of expected to see some kind of Mad Max style interactions among various rogue characters in an abandoned dwelling, which in itself would have made a timely social commentary on the city where it was performed. Alas, what we ended up with was a mishmash of ideas and styles that were at odds with each other, and it grew more confusing as the opera progressed.

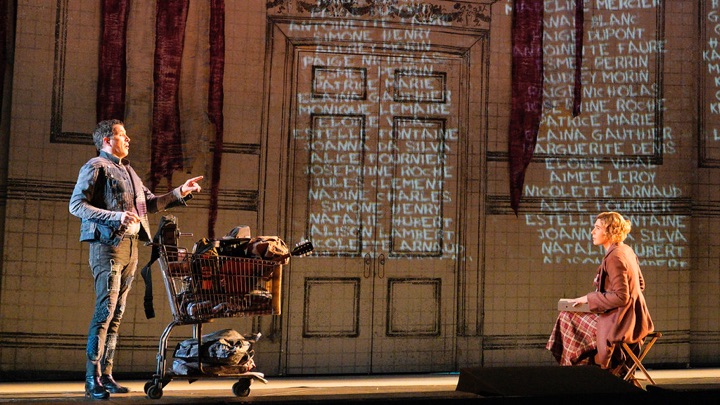

Erhard Rom’s mostly static set split the House into two sides with the crack in the middle, which seemed to account for the downfall of both the House and the society. In between these sides, a raised platform was placed, where some actions happened during the opera. I said some, as inexplicably Cavanagh and Rom decided to place the singers right in front of the stage, with a three-piece screen divider with the silhouette of the House (adorned with tattered American flags) placed directly behind them for most of big arias and ensemble pieces; it was there for Leporello’s Catalogue aria, Donna Elvira’s “Mi tradì”, the great sextet of Act 2, etc etc.

Personally, I found the constant use of this stage mechanism got more and more predictable and even tedious, and honestly, it made the whole performance felt merely like semi-staged.

However, I had to give Rom credit for the pièce de resistance of the night, the towering 24-feet tall bust of Commendatore. Yes, the arrival of the statue of the Commendatore was replaced with the appearance of this giant bust and sung off-stage in this production. While it might be awkward dramaturgically, needless to say the sight of it—which then split in half and swallowed Don Giovanni in the final scene—truly created a jaw-dropping spectacle and provided the show with a much-needed burst of excitement that late in the game.

Costume designer Constance Hoffmann tied the costuming for the characters to the past chapters, as she said “The shattered remnants of the worlds of Figaro and Così fan tutte are collected and repurposed in the clothing of both classes.” While in itself that wasn’t a bad idea, nevertheless the widely differing nature of the costumes—ranging from steampunk fashion for Zerlina/Masetto, formal evening attire for Donna Anna/Don Ottavio and ruffles for Don Giovanni—gave impression of more unfocused vision than a resourceful one.

One instance struck me as particularly misguided … Donna Elvira wore a wedding dress (complete with a veil) as a masquerade costume to attend the party at Don Giovanni’s quarter! I’m pretty sure no woman in her right mind would ever do that!

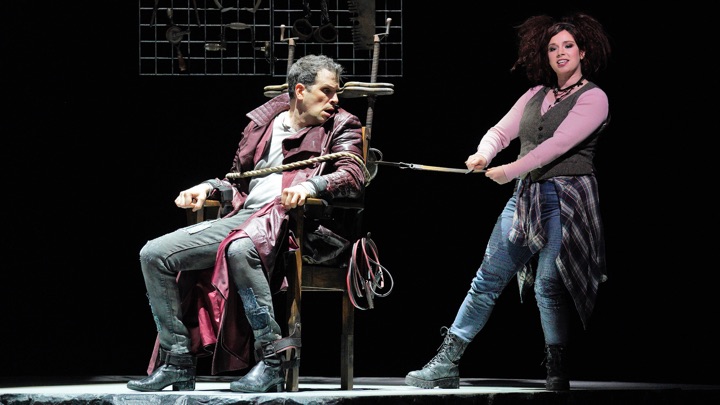

The choice to perform the full 1788 Vienna version of the score too, presented another problem for the staging, particularly with regards to the almost-never-performed Zerlina/Leporello duet, “Per queste tue manine”. Cavanagh staged the scene in a Saw-like torture chamber that truly came out of nowhere (maybe in the future we all will have one in our basement?) Luckily, that moment was saved thanks to the perfect comedic timing of both Christina Gansch and Luca Pisaroni, which provided the audience with one of the highlights of the night!

Personally, the chief issue of the staging was the decision to confine the whole proceeding in a single space. Of the three Mozart/Da Ponte collaborations, I believe that Don Giovanni is the one that has the most specific cues regarding time, place, movement, even the class types of the characters (the Dons and Donnas are definitely the elites, which won’t be otherwise caught mingling with the Zerlina/Masetto (or the chorus) types).

Hence to restrict the action into a single House without making significant changes to the libretto was almost impossible, methinks. Case in point, without the cemetery scene (the ghostly voice of the statue was sung off-stage, with his silhouette reflected on the wall), the whole ending wouldn’t make sense. Also, how did a ruined House have a sparkling brand new chandelier in time for Don Giovanni’s demise?

All these staging inconsistencies wouldn’t have been so frustrating if the music-making of the night wasn’t of the highest order. A lot of the cast members were colleagues and friends who performed the same roles together previously.

Husband and wife Etienne Dupuis and Nicole Car originated the roles of Don Giovanni and Donna Elvira in the bleak Ivo van Hove production (which will travel to the Metropolitan Opera next season) for Opera de Paris in 2019; Car also returned—with Gansch, Adela Zaharia (as Zerlina and Donna Anna respectively) and conductor Bertrand de Billy—for the revival of that same production in Paris last February.

The camaraderie among the cast was evident from the stage, making the performance worked more like an ensemble piece; they played off each other’s strengths nicely. Nowhere was that more apparent than in the case of the three sopranos, where each provided a distinctive personification (both in the vocalization and the acting) of the three women of Don Giovanni.

Car—the very late replacement for Carmen Giannattasio (who withdraw slightly more than two weeks prior because of a surgery)—portrayed Donna Elvira with dignity, far from the cuckoo depiction that often came with the character. In her hand, Donna Elvira was simply a woman seeking for respect that she deserved, while she was still madly in love with Don Giovanni.

Car’s exquisite instrument particularly glimmered during “Mi tradì”, where she smartly used the coloratura to accentuate her frustration of Don Giovanni! On a lighter note, the blond wig that Car wore somehow kept reminding me of Edith Crawley from Downton Abbey, who in similar fashion sought respect (except from her family in Edith’s case)!

The biggest discovery for me that night was Zaharia, who imbued Donna Anna with the elegance demanded by the elite class but at the same time full of the vindictive rage. Zaharia’s beautiful voice sounded full and round throughout; the darkish tone she employed with dramatic flair (especially on the riveting “Or sai chi l’onore”) certainly enough to convince a man to do her deed! And, yes, similarly she did evoke Mary Crawley from the same TV series!

Gansch—who excelled as Dorinda in Orlando in 2019—completed the trio with a spunky personification of Zerlina, full of life yet with a penchant for violence, as evident in her interaction with Leporello (above) and with Masetto. Her Zerlina, aided by the steampunk getup, personified not merely a simple peasant girl, but a strong independent woman; and her voice (the brightest of the three) provided a nice contrast with Car and Zaharia.

The men too were no less impressive than their female counterparts, albeit in smaller roles. Not just a buffo character, there was a certain world-weariness in Pisaroni’s take on Leporello, as if he was trapped in a world that he couldn’t escape from. While his low notes might not as secure as when I heard him previously, his characterization was so wholesome that one couldn’t help but to root for Leporello.

As the sole tenor role in the opera, Amitai Pati managed to make the role of Don Ottavio less docile than usual. My biggest problem with Vienna Version was that “Dalla sua pace” coming after “O sai chi l’onore” always had the effect of turning Don Ottavio meek and unassertive, even though it was a gorgeous aria on its own. Pati sang it with grit and determination, and the audience responded enthusiastically afterwards.

With his booming voice, bass Soloman Howard—who made headlines with his onstage marriage proposal last September—certainly made his presence felt as Commendatore. It was such a pity that Howard sang most of the lines off-stage! Unfortunately Cody Quattlebaum didn’t make much impression this time as Masetto, unlike his spectacular turn during Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra performance of Johann Sebastian Bach’s Coffee Cantata about a month before the world shut down in 2020.

Conductor de Billy, who made SF Opera debut with this performance, led the SF Opera Orchestra in a brisk and exciting reading, after a somewhat tentative account of the famous Overture. There were a couple of times I thought I was listening to a period instrument band! I was particularly struck by the clarity that he coaxed from the Orchestra; I’d never heard the arpeggios that run underneath the voice during Zerlina’s aria “Batti, batti” so vividly before!

This performance also marked the debut of the newly appointed Chorus Director of San Francisco Opera, John Keene. Keene succeeded Ian Robertson, who retired last December after leading the Chorus for more than 35 years. Judging from this performance, I expected bright future for the Chorus in the coming years.

I save the best for last, as every performance of Don Giovanni will live and die depending on the title role. Dupuis, whose handsome face was plastered all over town to promote Don Giovanni, truly embodied Don Giovanni wholeheartedly. In an interview with SF Opera staff, Dupuis admitted that he saw Don Giovanni as “absolutely a predator”, not merely a seducer, and he embraced that thinking in his characterization.

There was a certain aura of danger around him, from the way he walked, he smirked all the way to how he tried to rape Donna Anna by choking her in the beginning, followed by the cold-blooded murder of Commendatore. It was a role that so much personified evil that Dupuis got some booing during the final bows (that he heartily responded).

Vocally, it was an impressive tour-de-force of a performance, full of nuances and colors. He varied his tone from song to song; “Là ci darem la mano” sounded sweet with sinister undertones, while the Champagne Aria and the dinner scene were sang with reckless abandon. Not to mention, he peppered “Deh, vieni alla finestra” with delicious pianissimi! If I might nitpick, I only wished he could be more audible during the final confrontation with Commendatore; it was as if the giant styrofoam bust not only swallow Don Giovanni, but also his voice!

So run, don’t walk, to see a performance of Don Giovanni at War Memorial. If what you see on stage doesn’t make much sense, just close your eyes and imagine Mozart himself conducting from Heaven, as a performance of this caliber is hard to find!

Photos: Cory Weaver/San Francisco Opera