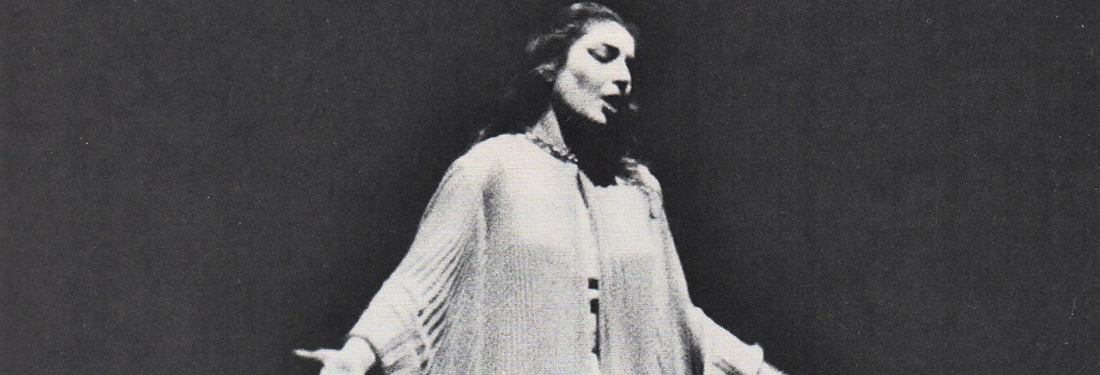

Sabine Devielhe, whose “coolly limpid voice has rarely sounded so bewitching” in Achante et Céphise.

When someone would diss, say, John Milton, an ex of mine would quip “it’s not Milton who’s being judged!” I admit I often feel the same way when people dismiss the wonders of “baroque opera.” That sweeping term unfortunately tends to describe any work composed over a century-and-a-half span: from the very end of the 16th century when the art form began to the rise of Classicism in the mid-1700s.

For those who complain (not entirely unfairly) that Handel operas are “just a string of da capo arias,” I sometimes mutter to myself, “Have they ever tried Rameau?”

Although Rameau and Handel were born just seventeen months and 500 kilometers apart, their operas could hardly be more different. Handel composed his first at 19 and more or less stuck to opera seria for more than 40 works until he gave up to concentrate on oratorios. Rameau waited until age 50 to write his first opera—Hippolyte et Aricie—which followed the tragédie en musique paradigm devised by Lully decades earlier.

Rameau then kept tweaking the tragédie while dancing between various sub-genres: opéra-ballet, comédie-lyrique, acte de ballet, and pastorale héroïque, Unlike the singer-focused opera seria, French operas of the late-17th and early- to mid-18th centuries, though no less formal, are far less aria-driven and feature many choruses and extended dance sequences. Those works have always struck me as possibly more accessible than opera seria to the “average” opera-goer.

The operas of Rameau, the greatest French composer of the 18th century, have lately been much on my mind and in my ears as a cache of terrific CDs have been arriving. Few studio recordings of the standard repertoire are being made these days, hence the wild excitement about the sessions held earlier this month for a new Turandot starring Sondra Radvanovsky and Jonas Kaufmann.

On the other hand, five (!) Rameau operas have been released on CD in the past months: Les Indes Galantes, Dardanus, Platée, Les Paladins and Achante et Céphise! I’ve been torn between last pair as to which I love and listen to more.

When it was released late last year Erato’s Achante et Céphise ou La Sympathie conducted by Alexis Kossenko caused considerable excitement as the three-act 1751 pastorale héroïque had never before been recorded nor even performed in France since the 18th century.

The work though isn’t quite as unknown as the pre-release publicity trumpeted as a 1983 concert performance was broadcast by the BBC and has been available on Trove Thursday since 2018.

However, the Erato release uses a new critical edition and is a bit longer than that English performance.

Rameau’s colorful imagination is always evident in Achante, especially in its pioneering use of clarinets, heretofore unused in French orchestras. Kossenko’s splendid Les Ambassadeurs-La Grande Écurie revel in the fanciful instrumental writing: for example, the arrestingly dramatic overture is one of Rameau’s finest. But the bland story of besieged lovers fails to take flight which might account for its being ignored for decades.

The Achante and Céphise, Cyrille Dubois and Sabine Devielhe, are near ideal. The soprano’s coolly limpid voice has rarely sounded so bewitching, and it blends beautifully with Dubois’s heady, yet virile haute-contre in their many duets.

As happens in other Rameau operas, the lovers don’t always get the most exciting music. David Witczak as the lovesick genie Oroès injects welcome conflict as he kidnaps Céphise. His firmly forceful baritone strikes sparks, and one hopes to hear him as many of the other Rameau villains created by the wonderfully named Claude-Louis-Dominique de Chassé de Chinais!

Witczak and the chorus, Les Chantres du Centre de musique baroque de Versailles, join together thrillingly at the opening of the third act when the genie astride a dragon arrives to torture the imperiled lovers. Judith van Wanroij’s more pointed soprano contrasts with Devieilhe’s, and she dominates the first act as the beneficent Zirphile who eventually reunites Achante and Céphise.

Despite already knowing the 1983 Trevor Pinnock broadcast, I was immediately seduced by Kossenko’s gorgeous reading and listened to it repeatedly while I awaited Valentin Tournet’s new recording of Les Paladins, whose US release was delayed until the end of January.

I was particularly eager to hear it as I had been impressed with the young (he turns 26 next month!) conductor’s smashing recording of Les Indes Galantes.

Though he commits a serious misstep in interpolating the well-known quartet “Tendre amour” into Les Sauvages, Tournet’s delicious Indes Galantes rapidly became my favorite version of Rameau’s most popular opéra-ballet.

Composed in Rameau’s late 70s, Les Paladins was his first full-length work in nearly a decade and last final performed opera. But one would scarcely mistake its richness of comic invention and extravagantly energetic dance music for the work of an old man. However, its loony libretto based on works by Jean de la Fontaine (which are reproduced in the lavish libretto included with the 3-CD Château de Versailles set) may have kept it mostly in libraries.

However, the blissfully entertaining Les Arts Florissants staging of Paladins which I saw at the Châtelet in both 2004 and 2006 demonstrated just how magnificent this late score was. Happily, Tournet’s blissfully infectious version achieved the near-impossible: it made me forget the LAF version which remains available on DVD.

Sandrine Piau, William Christie’s Nérine, starts out weakly as Argie, but soon recovers her usual crystalline form, while in turn Anne-Catherine Gillet sparkles delightfully as Nérine. Her perky teasing of Florian Sempey’s pompous Orcan is a highlight of the first act.

Mathias Vidal’s lively Atis may lack the smooth tone of Topi Lehtipuu on the LAF DVD but his witty energy enlivens all his appearances. Another haute-contre, Philippe Talbot doesn’t have much to do as Manto, but his suavity promises much for the future in Rameau’s demanding tenor roles.

While Tournet’s La Chapelle Harmonique isn’t quite as polished as Kossenko’s forces, they bring enormously inviting energy and good humor to Rameau’s entertaining romp. Both of Tournet’s opera recordings and Vidal’s Rameau Trionphant collection come from the prodigious Château de Versailles label which after just four short years was recently named label of the year at the 2022 International Classical Music Awards.

Although the three previously mentioned titles were recorded especially for CD, another estimable Rameau opera on the Château label originated from a live performance in the Versailles opera house: Les Boréades conducted by Václav Luks.

It may not displace John Eliot Gardiner’s definitive Boréades on Erato, but Luks’s is very persuasive and well worth hearing. It also includes a libretto and translation which Gardiner’s did not.

Vidal’s solo CD is devoted to works composed by Rameau for Pierre de Jéliote mirrors one released some years ago with Jean-Paul Fouchécourt.

Vidal’s high energy and taut singing can be a bit exhausting for a long stretch, but the recording’s deluxe presentation with chorus could make an endearing Rameau introduction.

A second CD devoted to Jéliote, the composer’s preferred singer, was simultaneously released on Alpha Classics with Belgian haute-contre Reinoud van Mechelen conducting his own orchestra A Nocte Temporis.

Though it includes excerpts from six of his operas, van Mechelen’s survey of music written for Jéliote goes far beyond Rameau to feature arias by nine other composers including a few I’d never heard of before.

Van Mechelen’s smoother approach might be more listener-friendly than Vidal’s, and he’s definitely in better voice than he was for his previous tribute disk to Dumesny, Lully’s most valued haute-contre. But ultimately I’d give the nod to Vidal.

Tenors aren’t the only ones who get all-Rameau CDs: Devielhe’s divine 2013 collection also led by Kossenko would be my urgent recommendation anyone wanting a superlative Rameau sampler.

English soprano Carolyn Sampson has released two French baroque discs, one entirely of Rameau works, with another devoted to Marie Fel, the composer’s favorite soprano.

Alas, performances of Rameau’s operas are not easy to come by in the US. Since the early 1990s, Les Arts Florissants has been very regular in bringing them to New York, and Mark Morris’s Platée has been seen on both coasts. There were plans afoot to bring Platée back, but the pandemic intervened, and I’m not sure if that revival is still on. A few years ago, Opera Lafayette produced the rare Les Fêtes de l’Hymen et de l’Amour which was also staged by Philharmonia Baroque.

But, in the meantime, these splendid discs can and should be enjoyed over and over again. And another is due next month: Nouvelle Symphonie, Marc Minkowski’s sequel to his very successful Rameau mélange Une Symphonie Imaginaire.

One final note: a serious disagreement exists about the spelling of Céphise’s paramour. For decades, I’d known the opera as Acante et Céephise, but when the Kossenko version was scheduled for performance in Paris (but eventually cancelled) and the recording was announced, the title suddenly became Achante et Céphise.

Graham Sadler in his immensely helpful The Rameau Compendium suggests, “The spelling ‘Achante’ encountered in some modern sources derives from a misprint in the proofs of the engraved score, eventually corrected by Rameau.” To further muddy the waters, the back cover of the upcoming Minkowski CD cites Acanthe et Céphise.

Sacrebleu!

[La Cieca reminds the cher public that when they shop on Amazon, they should please use this link in order to help support parterre box.]

Comments