The opera being given that night was Andrea Chénier, a seemingly excellent choice. I had already written the first part of the following article and I have left it unchanged. However, you can tell what I was up against…

Review of Everett Helm in Musical America:

The commonly held notion that opening night at the Metropolitan Opera is more of a social than an artistic occasion would appear to have some basis. This year, at any rate, it certainly did. The earliest opening in Met history took place on October 15. Mink, ermine, diamonds, emeralds and white ties were strongly in evidence.

The opera chosen to start this season on its merry way is a prime example of a “vehicle” for the splendid voices which the Met has. Umberto Giordano’s “Andrea Chénier” is no operatic masterpiece. The story itself has dramatic possibilities galore and is superficially dramatic even in this version. But Giordano’s music is too weak and too unoriginal to make the drama really credible. The discrepancy between the cliché-ridden score and the terrible events of the French Revolution is glaring. And the Met’s staging, which dates back to 1954, did nothing to bridge this gap.

So “Andrea Chénier” remained a vehicle for Franco Corelli in the title role, whose high notes brought forth storms of “bravos” and who seldom sang below a forte during the entire evening; Eileen Farrell as Maddalena, whose generally good performance was marred by frequent pushing of her voice; and Robert Merrill, who gave an excellent accounting of himself as Gerard. In supporting roles, Jean Madeira (Madelon), Rosalind Elias (La Bersi), Lorenzo Alvary (Mathieu) and Mignon Dunn (Countess) contributed isolated bits of good singing and acting to a performance without profile. Fausto Cleva conducted energetically and did what he could to bring continuity into this random production, which no amount of flogging can bring to artistic life.

That review was actually reprinted on the Met Archive website. I have no doubt that Mr. Bing agreed with it, but why, then, did he choose it for Opening Night? I would venture to say because he knew that it, and all the other performances, would sell out. My thought is that it sure was a more appropriate choice for an opening night than this season’s sparkling Dead Man Walking. Unfortunately, it was never broadcast. There are, however, many performances of Chénier from the Met and elsewhere with Mr. Corelli, and there are two excerpts from later in the run easily found online of Eileen Farrell singing her aria and the final duet (which accounts for considerably more than half her role).

When asked to do one of my exposés for Andrea Chénier, my immediate thought was, “Gee, I can just copy the Gioconda essay and change the word ‘Gioconda’ to ‘Chénier.’” Consigned to the dumpster of operatic trash, like Gioconda, Chénier enters the pantheon of unjustly maligned operas thereby falling into the category of “Operas that Critics Love to Hate.” And like Gioconda, the opera is haunted by the ghosts of Zinka Milanov, Renata Tebaldi, and Maria Callas. And if you read my Gioconda, you know who the winner will be.

Though Chénier was composed 20 years later, like Gioconda, it was written in a style and in a period that was seeking something new. In keeping with the theme of the French Revolution and the somewhat recently published A Tale of Two Cities, Umberto Giordano was attempting to compose a far, far better thing than had ever been done: Verismo disguised as Grand Opera. With the exception of Cav & Pag and, of course, Puccini’s masterpieces, Andrea Chénier with its rhapsodic and sweeping score is the most popular of the verismo operas. On the stage Andrea Chénier can be a tremendously exciting experience with strong characterizations for its principals, abundant small roles, and a vigorous, diversified plot full of atmosphere and incident. Names of real people, real characters, real locations abound. Having produced many school shows, Andrea Chénier always makes me think of choosing the right show for a school, one with many parts for many students… Hello, Dolly! and Oliver! are perfect examples.

Undeniably, Chénier’s best moments are superb and quite individual. The Act III tribunal scene can be riveting. On the other hand, when the action is taken away and one is left alone with just the music, there can be some note-spinning passages in which the orchestra runs on and on without saying anything in particular. The ballet is as banal as Adriana Levouvreur’s. Against the highlights, some of the pseudo-pastiche 18th-century music, though charming as background, is not in itself quite up to standard and sticks out by a mile.

Ah, but those highlights! As Gioconda and Adriana are prima donna vehicles, Chénier is definitely the tenor’s opera. He has four arias, one per act, and at least the first one, the impassioned “Improvviso” is one of the great arias of the tenor repertoire. Certainly the same can be said for the soprano’s “La mamma morta” and the baritone’s “Nemico della patria.” And that final duet! Perhaps it’s not the greatest duet ever written, but it sure is the most exciting.

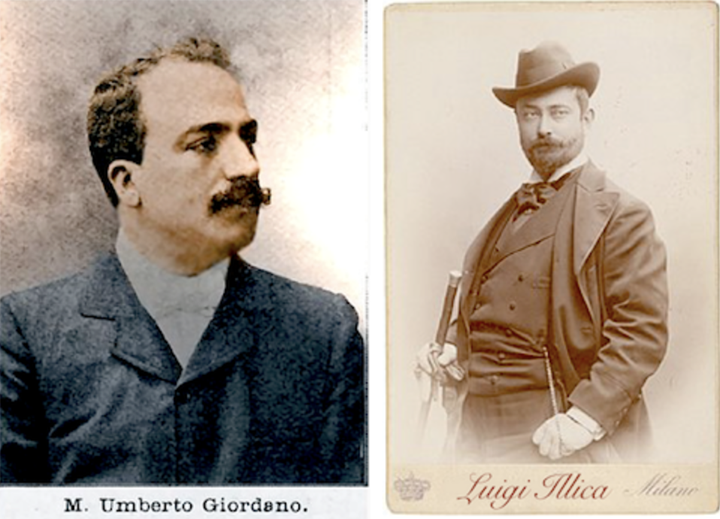

Andrea Chénier was first performed at La Scala on March 28, 1896. That is the same year as La Bohème premiered. The libretto for both was written by Luigi Illica who had already written the libretti for La Wally and Manon Lescaut with Iris, Tosca, Madama Butterfly, and many others still to come. His personal life sometimes imitated his libretti … he lost his right ear in a duel over a woman.

Giordano was born in Foggia in the southern part of Italy on August 28, 1867. Interesting trivia: his middle name was Menotti. He studied at the conservatory in Naples. As the youngest entrant, he managed to place sixth (out of 70) in an 1889 contest that was famously won by Mascagni’s Cavalleria Rusticana; he so impressed the publisher, Casa Sonzogno, that he was given a contract. Mediocre if not outright failures ensued and he was living the life worthy of the first act of La bohème. He was successful enough, though, and Sonzogno had enough faith in him to have an opera produced at La Scala in 1896. This was Andrea Chénier and proved to be his only major success. Fedora, starring the then upcoming Enrico Caruso, followed two years later. In 1915 his Madame Sans-Gêne premiered at the Metropolitan Opera. He died in Milan on November 12, 1948 at the age of 81never again having achieved the success of Chénier.

WHO’S WHO

Of the operas about which I have written, Don Carlo(s) has interested me the most as the characters and situations were based on real historical figures and events. While Andrea Chénier is hardly as profound as Don Carlos, it has been thought-provoking to delve into the history and life of the real André Chénier.

A listener with some knowledge of the French Revolution and the personalities behind it will probably find the opera more colorful and interesting than one without that historical background. Set in Paris, the first act shortly follows the storming of the Bastille on July 14, 1789, though that’s never mentioned and ignored by the aristocrats. The later acts take place five years later during the 1794 Reign of Terror, the same year as the events in The Dialogues of the Carmelites occur. Giordano’s Chénier bears scant resemblance to the historical one. André Chénier was born in Constantinople (which is actually mentioned in the opera) on October 30, 1762, the high-born third son of Louis de Chénier, an officer at the French embassy. He spent most of his childhood in southern France with an aunt but in his teens moved to Paris with his Greek mother. He became a fervent admirer of everything related to the ancient Greek language and civilization. He was stimulated by the artists and intellectuals he met at his mother’s la belle Grecque weekly soirées. Within him was a sensitive artist with a rich inner life, one that allowed him to express himself with poetic inspiration. He rediscovered Greek classic literature and gave it renewed beauty in his own powerful verses restoring lyricism to French poetry. His poetry was emotive and sensual and pointed towards the Romantic Movement.

Appeal of the last victims of terror in the prison of St. Lazarus. Chénier appears seated at the foreground’s center.

Painting by Charles Louis Müller, (Musée de la Révolution française).

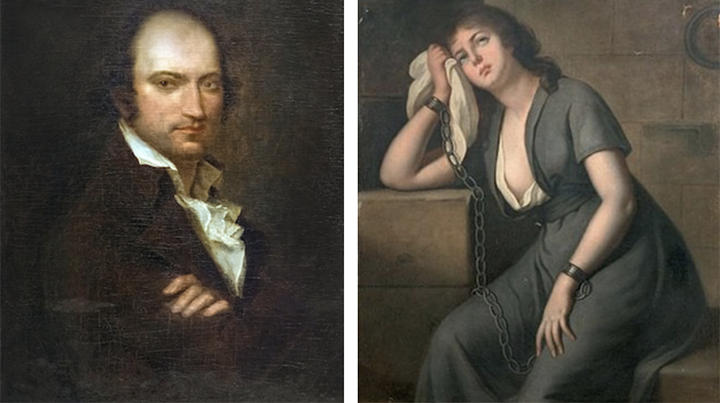

With the storming of the Bastille, Chénier subsequently started a short career as a political journalist, fighting eloquently against anarchy, injustice, and tyranny. In 1794, mistaken for his brother, he was arrested and sent to St. Lazare Prison – known as “one of the guillotine’s most plentiful pantries” and where he spent the last four and a half months of his life. There he met the poet Jean-Antoine Roucher (his friend in the opera) who became his confidant, and Aimée de Coigny, Duchess of Fleury. Chénier was attracted by her beauty and charm and inspired by Roucher to compose his best verses, those of “The Young Captive.” The poems he wrote in St. Lazare were concealed in a basket of laundry and sent beyond the prison walls to posterity. This contributed to the legend of Chénier and Aimée’s tragic love affair, which never did occur in real life. Hardly the tragic muse, Aimée has a succession of husbands and lovers. She was set free with a bribe to the prison guard. In her memoirs, there is no mention of Chénier and most likely she didn’t know she had been immortalized in verse and music.

André Chénier wrote his best poetry while in the prison of St. Lazare.

On July 24, 1794, Chénier was taken before the Revolutionary Tribunal, where he was accused with trumped-up charges of writing against freedom in favor of tyranny. The sentence: immediate death. On July 28, he was taken along with 37 other prisoners to what is now the Place de la Concorde; a poet until his last minute, Chénier with his friend Roucher, both started reciting verses on their way to the guillotine.

Ten days before Chénier’s death, the painter Joseph-Benoît Suvée completed this portrait of him – not exactly the romantic figure we would cast.

On the right Aimée de Coigny, La Jeune Captive

When we meet Chénier the character in the opera, it is at a soirée at the estate of the Countess de Coigny. The Countess is the superficial embodiment of a decadent society totally oblivious to the poverty around her and as Carlo Gérard, her footman, expresses, she represents those who are deaf to the voice of pity. Her daughter is Maddalena de Coigny; when we meet her, as expected, she is a naïve, spoiled teenager. Her agony is in the difficulty of deciding which frock to wear to make herself beautiful.

As soon as we meet Chénier, both the Countess unsuccessfully and Maddalena successfully challenge him to recite some verses. When he suggests love, Maddalena typically giggles (or cackles depending on the singer). But Chénier’s love is for that of country. In his great soliloquy, the Improvviso, he deftly constructs poetry to sound like a spontaneous and impassioned improvisation. Chénier is a thinker with ideals of humanity and how people should be treated; a poet obsessed by ideals of beauty, liberty, and honor. In his improvviso, he champions the downtrodden while denouncing the excesses of his hosts. It is his commitment that initially shakes Maddalena but ultimately allows him to lead her jubilantly to death.

Though Maddalena’s part is small compared to Chénier’s (two duets and one aria), it is her growth as a character that provides the real plot of the opera. In her aria, “La mamma morta,” Maddalena tells Gérard about the death of her mother in the flames as her home was burned by a mob. She tells of her companion Bersi selling herself on the streets to provide for her (why Bersi is mixed race is never explained). During her misery, love came to her and gave her the kiss of death. She finishes by telling Gérard to take her body for Chénier’s life. For a better explanation, see Tom Hanks’s Oscar-winning narration of the aria in the movie Philadelphia. More on that later.

The third principal, Carlo Gérard, is partly based on Jean-Lambert Tallien, a leading figure in the Revolution. Though initially an active agent of the Reign of Terror, he eventually clashed with its leader, Maximilien Robespierre, which eventually led to Robespierre’s downfall and the end of the Terror. As an opera figure, Gérard might almost be another lecherous baritone other than he starts and ends with good intentions. It’s in-between where the problem arises: his lust for Maddalena. [With the current Trial of the Century happening as I write this, I can’t help but think that when that opera is written, the ex-President will have to be a baritone.] Anyway, the interest of the character is that he has finer feelings and a conscience as he admits ruefully in the last section of his monologue, “Nemico della patria,” one of the great Italian baritone arias. It is a unique depiction of a character caught between lust and civility betraying his own ideals. Its richness of vitality and emotion and its riches of melodic imagination rarely fail to move.

The first act of Andrea Chénier is like a late 18th century version of La traviata’s early 19th century soirées. Name-dropping is rampant. Among the fictional guests at the Countess’s soirée are Fléville a novelist, Filandro Fiorinelli, a musician who plays the harpsichord, and another poet, The Abbé, besides Chénier. Many names abound in the following acts, whether they’re in them or not, that are not fictional. Necessary to know is that the king Louis XVI and his wife Marie Antoinette were both executed in 1793. What followed was known as the Reign of Terror, from September 5, 1793 to July 27, 1794. Acts II, III, and IV take place near the end of that period. The Revolutionary Tribunal and the Committee for Public Safety, under which Chénier was tried, were established and during which over 15,000 were guillotined in France. Jean-Paul Marat was a physician turned journalist. He was immensely popular and became known as “l’Ami du Peuple.” To the jealous Robespierre’s disgust, he became a heroic martyr and shrines were erected to his memory after he had been famously killed in his bathtub by a revolutionist, Charlotte Corday. This was further immortalized in the play Marat/Sade. Maximilien Robespierre (not in the opera) was the most influential and most feared member of the Public Safety Committee. Antoine Fouqier-Tinville was the public prosecutor of the Tribunal. He was nicknamed the Provider of the Guillotine. René Dumas (no relation that I know of to the better-known Dumas-père and Dumas-fils) was the President of the Tribunal. Charles-Henri Sanson (not in the opera) was the public executioner. François Chabot (also not in the opera) was a former friar known to have been involved in dishonest financial deals. When Gérard attacks Chénier at the end of Act 2, he cries “I shall steal you from Sanson!” to which Chénier replies, “You fight like a monk. Am I fighting Chabot?” I guess it made sense to them. One of the accusations made against Chénier in the third act is that he fought alongside Charles François Dumouriez, the French Minister for Europe and Foreign Affairs. He had been a general who won signal victories for the French Revolution in 1792–93 and then traitorously deserted to the Austrians.

To help make a little more sense, clothing referred to in the opera includes “sans-culottes,” meaning, “without breeches.” Because they donned workers’ long trousers instead of the knee-breeches of aristocratic dress, those who wore them were the rabid revolutionaries mostly of the lower class. The Incroyables and their female counterparts, the Merveilleuses, were members of a fashionable aristocratic subculture who adopted exaggerated modes of dress. The incroyable was the dandy of this period affecting a large hat tilted at a rakish angle. The merveilleuse wore a long, loose sometimes revealingly-cut dress, sandals or bare feet, and a fantastic bonnet.

Ever wonder why Mario del Monaco’s hat is tipped?

The Incroyables and the Merveilleuses were members of a fashionable aristocratic subculture in Paris while the sans-culotte definitely were not.

Next time, I’ll be discussing the singers that made this opera so thrilling. I bet you can guess who they might be…