Edita’s daughter Klaudia, a lovely, sweet young woman, picked me up from the airport in Zürich, and made sure I was situated on the right train to Strasbourg.

This time around, though, Edita was visibly tired, and by her own admission, a bit irritable. That year of 1993 was her 25th anniversary in opera. The years of constant travel, living out of a suitcase and in hotels, the logistics of millions of details to attend to, having to be “on” all the time and being ever better than the last performance had taken its toll. As her fame and legend grew, so did additional demands for interviews and press appearances, which seemed to her incessant and redundant—“always the same questions!” But then a few seconds later, she conceded, “But this is part of the career, no?”

Edita mused to me at the direction her life had taken: “When I first started out in Vienna I could not even imagine in my dreams of the life I now have, and I am of course very grateful to do what I love, as well as having the love of the public but Mein Gott it is sometimes too much, really. I miss my daughters so much, they are needing me, but I must work to support them and this life. This is what I have to do, I cannot and don’t want to do anything else. Singing is my life.”

The bulk of the role studies, the musical analyses and historical precedents of singing in the manuscript for our book were largely in the can, but it still felt unfinished, vaguely unsatisfactory. Most of my reading related to opera was British and American-based. As it was going to be published in a German translation for distribution to like readers, my rough draft was curiously non-European in sensibility: it then read almost like a coloratura roles and traditions guide, with Edita as a current practitioner.

It also needed a deeper human element, more background history of Edita’s formative years, and what challenges she was met with in post-war, communist Czechoslovakia. Through a combination of research at the library, plus long discussions with Edita and Friedrich, a few of their associates, and other seasoned, international opera-goers, I was able to garner a stronger sense of the European arts and culture scene, in addition to the politics and operational methods of opera house administrations and managements.

This trip provided me with the most in-depth back story of her life yet. The conversations with Edita in Strasbourg, and on the phone for the next few weeks, were rather on the grim side, with revelations and details I had not expected to hear from her.

She related to me the trying events of her childhood. Her father, imprisoned for treason by the Czechoslovak state for a minor offense, returned home from incarceration a changed man. He became an abusive alcoholic who terrorized his wife and daughter, with them often having to escape their home to a safehouse from his death threats. While as a very young child, Edita became sickly and developed, along with an enlarged heart, a debilitating, severe form of rheumatism. She spent long periods in treatment and recovery, with recurrences that would resurface for years.

While this was all going on, Edita began to receive recognition for her singing, with the eventual admittance into the Bratislava conservatory, and studies also began with her first singing teacher. First operatic engagements in small provincial houses soon followed. She met and later married Stefan Klimo, a young musicologist and composer.

After securing a contract with the Vienna State Opera in late 1969, within a year’s time a pregnant Edita decided that she, Stefan, and eventually her mother should emigrate and defect to Austria, not only because Vienna promised a secure job and a new life, but of the intent to escape her father’s abuse. Complicating this endeavor were internal family quarrels and strife, in addition to contending with emigration bureaucracies.

The difficult birth of Edita’s first child Klaudia in early 1971 resulted in life-threatening health effects for both mother and daughter. Edita began to hemorrhage severely, needing transfusions, and this cycle of losing blood continued for a time after the birth, requiring additional hospitalization and treatment.

A second daughter, Barbara, arrived as Edita’s international career took off with Zerbinetta in the new Staatsoper production of Ariadne auf Naxos.

While her career prospered, problems continued to plague Edita’s family, with health issues inflicting her second daughter and mother, as well as her husband’s increasingly erratic and abusive behaviors. Stefan, had he been properly diagnosed, would have received the prognosis of acute mental illness, but it went unchecked and as a result, his emotional instabilities grew worse.

The precariousness of Stefan’s temperament caused Edita’s own health to suffer, culminating in a collapse of suspected heart trouble in July of 1982 while in Aix-en-Provence. During hospitalization, tests confirmed that her physical health was fine. However, what caused her collapse amounted to a nervous breakdown. Deciding she and her daughters could no longer be subjected to her husband’s psychotic behaviors, Edita filed for divorce. The following year, the depressed and troubled Stefan took his own life. In late 1984 Edita’s mother Etela died after a series of strokes.

I received all these details with stunned disbelief and a feeling of intense sadness for Edita. I had no idea whatsoever of the reality of the life of this strong, vibrant woman I had gotten to know, the traumas she suffered; the extent and the horror of her experiences was all very surreal to me. I remember vividly the sorrowful empathy she expressed for the man she married, the woebegone tone in her voice—”This poor man.. he was so very sick and tormented.. .I just don’t know, just don’t understand all of it.”

Even though Edita told me all these details with halting quietness, she did so without telegraphing a desire for sympathy. Wordless at first, I nevertheless, with great effort and uncertainty, finally said, in effect, “My God, Edita. I don’t know what to say, except I am so sorry to hear all of this, for you and your daughters.”

With a deep sigh she replied, “Yes, but you know? This is life like this for many people, I am not the only one.”

After the stay in Strasbourg ended, we all returned to Zürich, where I had almost two days left before I returned home to Michigan. I stayed at a hotel not too far from Edita and Friedrich’s home, to where they invited me for the day for further book work sessions. Their house, not surprisingly, was elegant and tasteful, but warm and cozy, not at all ostentatious or grand in style. Adorning some of the walls were a few stylized paintings of Edita by Ernst Fuchs, in her roles of the Queen of the Night, Violetta, and Donizetti’s Queen Elizabeth.

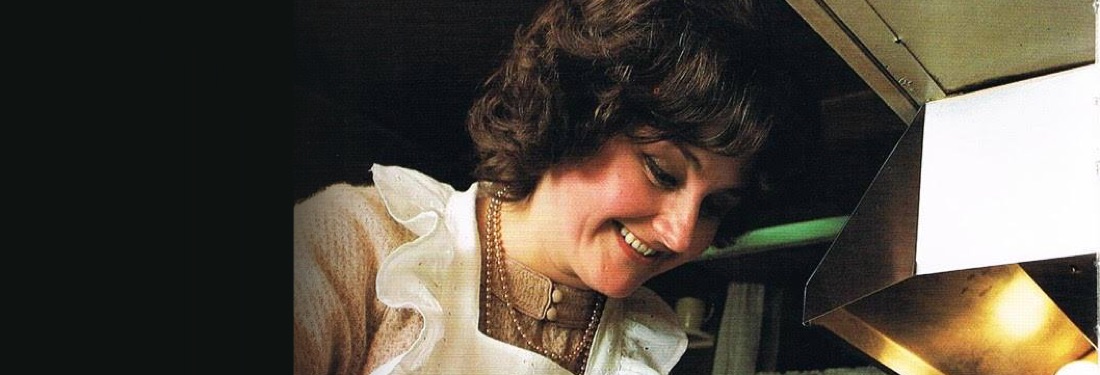

Toward 6:00, Edita suggested we stop so she could make supper, which was a tasty meal of beef strips, sauteed potatoes, and caramelized bananas. Simple, but hearty. Edita, Friedrich, Klaudia, and Barbara all made me feel at-home and welcome; I was treated not in the conspicuously formal manner of “company,” but as a trusted family friend. The conversation was low-key and understated, and I did not feel out of place.

On the flight home, I reflected back on all that I had learned. The disquieting details of Edita’s earlier years left me wistful, puzzled but with unstinting admiration for her resilience and tenacity, all the while keeping apace with motherhood and her demanding career.

Yet by the same token, I had the definite sense that all those demands that defied withdrawal, which kept her occupied and busy, was a compensating, saving grace for her. Wallowing in self-pity did not seem to be her thing in any case, but it could be she chose to deal with her torments and sorrows in private, and I did not for a moment even hint, much less push, for more than she wanted to offer.

Those conversations, though, never left me, and I have thought about them quite often in the decades since. Hindsight and life experience has better informed me as to the kind of background and existence from where Edita hailed, which, being from communist Czechoslovakia, was as about as far removed from my happy-go-lucky suburban American life as could be (one of her revealing statements, by way of example, was “I didn’t know until I lived in Vienna that you could buy lemons every day”).

A series of unusual, and almost eerily-apt synchronicities coincided from the time I began listening to and learning about Edita from Mitteleuropa* Over the years, from the mid-80s on, I developed acquaintances and friendships with an unusually high number of various Belgians, Serbians, Croatians, Germans, Austrians, Czechs, and Hungarians; a few of them were Jewish.

One of my closest friends of Serbian extraction, Nada Radakovich, was a high coloratura who sang in Germany; my voice teacher Phil Pierson, through a Hungarian friend of his, was friends with the German coloratura Ingeborg Hallstein, whom I met when I attended a dinner party when she visited Ann Arbor in 1990.

I not only had a close friend with which to hold forth on the coloratura repertoire and singing, but my conversations with the delightful Frau Hallstein proved to be invaluable as she answered my many questions; she had been a coloratura superstar in Munich in the 60s and 70s and elsewhere in central Europe, and her sagacity of insights proved illuminating.

However, it was my associations with all the assorted central Europeans who eventually, in a roundabout way, further informed me greatly in understanding Edita’s world, existence and where she came from.

There are many common factors in peoples who were born before, during, and immediately after World War II. They’re all byproducts of Nazism, the Anschluss, the Holocaust, and, where applicable, the takeover by communist regimes—from which came atrocities, pillaging, bombing, oppression, fear, paranoia, alienation, widespread starvation, and mass genocides. This was their environment. They lived amongst Americans who mostly had no clue, less of interest, in their previous lives. However, being an inquisitive sort, my indicated interest opened the floodgates.

The aftermath left most of my immigrant friends deeply scarred and traumatized, some marked by a fatalistic kind of despair. Jolly, cheerful, even stoical they could be, but their sensibilities were often marked by a very deep melancholy, sometimes of an underlying, marked pessimism, even abject bitterness, about people and the world. Paranoia and suspicion were often present. There is no doubt all of them suffered from various effects of PTSD. But they were a proud, forthright lot, and once they trusted you, their accounts, by turns, were spellbinding, terrifying, and downright shocking.

I didn’t witness any overt effects or manifestations of trauma from Edita stemming from her troubled early years. But it could easily be that I was too young to detect or intuit obvious signs—but more likely, she didn’t want to delve so deeply with me. She dealt mostly in facts, but there was no mistaking the grave, somber tone in my conversations with her in the recall of those grim circumstances. As far as I know, the book was the first time she even publicly dealt into these matters.

As the years went on, though, and as her clout increased, particularly after the book was published, Edita began being less guarded and speaking out more frankly in public. That meant offering blunt assessments on a variety of subjects, usually related to the frustrations with artistic and directorial egos, political sabotage, gossip and speculation, plus administrative bureaucracies in her profession.

I saw her becoming more fearless and even more revealing of herself and her feelings. In her 2008 documentary, The Art of Bel Canto, Edita unflinchingly, unapologetically admitted to the camera of her patience mingled with impatience, and to sometimes being “emotionally explosive.”

I certainly saw that side in Barcelona after the theft of her jewels, but that was by any measure an entirely normal reaction. But the Edita of the 21st century was a bolder, more outspoken and sagacious veteran of her industry, and though her keen sense of humor remained intact, she disdained to suffer incompetent fools or foolishness.

But Edita was never “explosive” with me. If I caught her on the phone at a bad time, she swiftly told me, “Niel, please, I can’t today,” and then would explain why, always with an apology and thanks—“Ja Ja, ciao ciao!” Occasionally there would be exasperation at her failure to find the right English word or expression, and she’d beg me, “Niel, please! Learn German!” Other times, after a run of performances, exhaustion and apathy would be present, with touches of pessimism creeping in: “It is not always so wonderful. I don’t understand people sometimes, you know?

You would not believe how many only care about themselves! I would like very much to be at home and in my garden and never sing again.” But then, a week or so later, good humor would return, and Edita would be chatty, effusive, and her love of singing back in full bloom. During these times, she would indulge me in my own fanatical love of singing and the intricate details I was fastidious about, such as ornamentation, textual considerations and the like. She’d tease, with that characteristic, mirthful chuckle, “You could sing this role tomorrow, no??”

The one aspect, then and long after the fact, that registered most strongly about Edita was that she was always unfailingly truthful with me at all points—exactly who she was, how she felt, straight on, direct. Proverbially, she didn’t have a phony bone in her body. There was never a “La Gruberova” on one hand and an “Edita” on the other.

Prima donna posturings and putting on airs were anathema to her being, and in fact her belting honesty was more often than not just delightful; she had an extraordinary sense of the sublimely ridiculous and her cosmic observations of human folly and egomania were epic. There were times when even the subtlest, silent facial reaction or the ever-so-delicately nuanced inflection of a lone word would induce me to loud howls of laughter, sometimes until tears came.

Edita was the best mimic I have ever known, and she could adopt a cartoonishly high voice as well as a fair replication of a basso-profundo, along with exaggerated facial expressions to match. Too, she could be overcome with a case of the giggles that were positively schoolgirlish in essence; when she got going, no one was as adorably fun and merry as she. Her outright laughter was loud, and deep from within.

Next: The ultimate 101 course on how to handle fame and success.

Comments