I had envisioned a long post-career period where she would enjoy spending more time with her daughters, being a grandmother, puttering around in her garden, and resting serenely on the laurels of an outrageously successful long run as one of the premier artists of her time, punctuated by occasional public appearances, yet another award ceremony, and what would inevitably be a series of celebratory career retrospectives. Maybe a few masterclasses, which she had started giving, maybe even a song or two for an event.

Definitely dinner with her sometime, upon a belated return to Europe (my dreams throughout the years have been marked by jetting across the Atlantic for a surprise visit).

Never to be.

Here I will share my reminiscences and experiences on the woman I got to know behind the artist, of how my association with her came to be.

Edita’s death affected me almost as much as my dad’s, which happened six weeks after high school graduation, in 1982; the loss of my dear father when I was 19 left me broken and dispirited. I had nothing in store for my future, no motive or incentive to do anything toward that end.

As my parents determined the tone of my childhood, Edita, through her art and by her actions, wound up setting forth the dominant path for my adulthood.

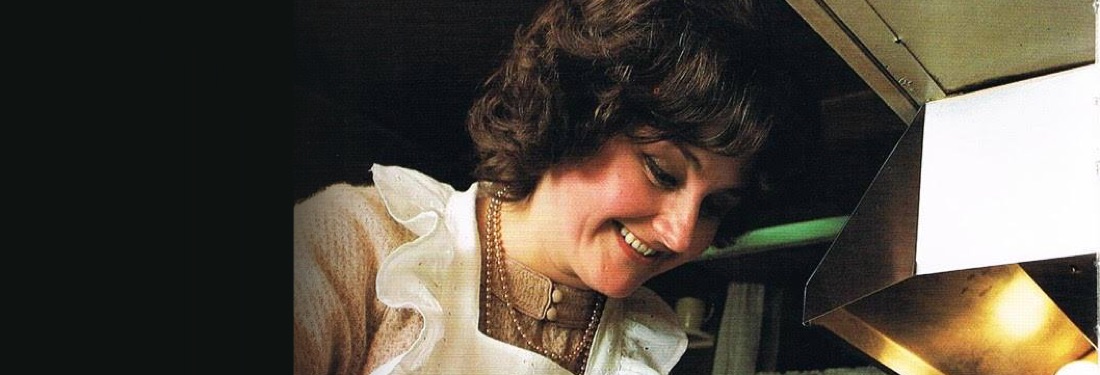

The following summer, in 1983, the course of my life changed by the purchase of Gruberova’s French and Italian Opera Arias LP. The first minute alone, of the first track, Delibes’ Bell Song, with its otherworldly pianissimo high E, followed by descending staccati, buzzed and piqued my senses with a new kind of wonder and astonishment, and the listening of that album that afternoon began the charting of a new path of musical awakening.

Dazzled by this extraordinary coloratura virtuosa, I wound up acquiring every single recording she ever made over the succeeding months, and the immediate acquisition of every new release from then on. It became an almost sacred addiction of sorts to hunt down everything she put out. Die Zauberflöte, the EMI recording under Bernard Haitink, featuring Edita’s Queen of the Night, was the first full-length opera recording I ever bought (remember the high price of those first digitally mastered LPs?)

I bought my first VCR strictly to record and save the Salzburg Festival’s Ponnelle production of Die Zauberflöte, which was the first time I ever saw Edita in actual performance; and for the Ponnelle film of Rigoletto.

La Gruberova became my muse in the pursuit of understanding music and opera. I chuckle when I recall looking at the texts and translations sheet to her Decca recording of Mozart Concert Arias, and asking my mom, “What language is this?”

I wanted to know what was being communicated, and so every single opera recording I bought had me looking at the libretto and translation and studying it. I wanted to know more about this then-mysterious fabulousness of an artist, and I haunted the public and University of Michigan School of Music libraries poring through domestic and international periodicals for reviews, interviews, and reports. I made copies of everything I found and subsequently started a Gruberova scrapbook.

I found the address of the Vienna State Opera and sent Edita a fan letter. A few months later, to my happy astonishment, she sent me a signed photo.

When Edita’s 1983 EMI recording of Lucia di Lammermoor was released, I did my first ever complete study of an opera using a score. I learned what musical notations meant: dynamic gradations, legato bows, accents, fermatas, and interpretive instructions.

I noted Edita’s unusual fidelity to Donizetti’s markings; it was an important milestone, for it accelerated my deepening understanding of opera and music (in a rather fitting twist of fate, I wound up writing the booklet notes for two out of three of Edita’s complete Lucia recordings). I bought practically every book I could find about singing, operatic lore, singer biographies, and gradually added more vocal scores to my collections: Mozart and bel canto became my central focus.

In my Music Appreciation class at Eastern Michigan in the Spring of 1986, I wrote a 20 page paper on “The Coloratura Art of Edita Gruberova.” Even though it was out of the scope of the class and it couldn’t be admitted as a class credit, my instructor, Edward Szabo, agreed to read it and gave me an evaluation grade of A+ and wrote, “You need to work on your grammar and style, but you essentially write like a seasoned critic highly steeped in opera!”

It was my study of the Lucia score that figured prominently in my paper, as well as the Queen of the Night’s two arias, in which I offered musical and interpretive analyses.

Mr. Szabo summoned me after class. “Whatever you do with your life, you should write music criticism,” he insisted. Wanting to hear Edita for himself, he asked me to bring a record of hers in. I brought in the French and Italian Opera Arias LP, and he played the Bell Song for the class. The MTV-age students looked puzzled and slightly addlepated, but Mr. Szabo, former conductor for The Ann Arbor Symphony, was enraptured: “What a stunning voice! Those high notes are unbelievable!”

When the Chicago Lyric Opera announced Edita to star in its 1986-87 season production of Lucia di Lammermoor, I quickly bought two tickets. About a month ahead of the performance date on November 22nd, I suddenly had the wild idea of sending my college paper to Edita, in care of the Lyric Opera.

My mom drove us there. We saw the performance. Despite the shoddy sets, the massive cuts in the score and the minimal direction, I essentially heard what I heard on Edita’s EMI recording: highly skilled, polished. But with a huge difference. Whereas on the recording Edita’s tone sounded a bit hard and narrow, in the house the voice just bloomed and spun out with these incredible timbral overtones that projected out into the spaces of the theater.

I will never forget in the cadenza with flute when she eased into a long-held, pianissimo high E flat. Geraldine Farrar’s famous memory of Melba’s high C described the way it floated out into the expanses like a “ball of light.” This was the effect of that crystalline, gleaming E-flat of Edita’s.

It took on a life of its own, still resonating when the loud, hollering, feet-stamping ovation began. The balcony shook. I will never forget that. The November 1st broadcast captures this moment, at 50:27:

After the Mad Scene concluded, I suddenly became aware of the fact that Edita might actually leave, since her role in the opera was done. Anxious that I might miss her, I made my excuses to my puzzled mom, and hastened to the backstage area. I found her dressing room door slightly ajar. I knocked, and through the small opening I saw Edita having her wig removed.

“Just a minute!” she called out. I waited for what seemed like an eternity, nearly breathless with anticipation. She opened the door and I was unprepared for what was before me: Edita, dressed in a cobalt silk blue dress with a peplum, was drop-dead gorgeous. Her complexion on that wide, Central European face was extraordinary, like gleaming, slightly tinted alabaster.

She smiled at me, and I stumbled and fumbled (I think) as I introduced myself, and asked if she had received the 20-page paper I had written on her. Her eyes opened wide and she exclaimed in her most charmingly accented English, pausing every so often to find the right words, “You are Niel?? Yes I read it, Mein Gott, how do you know so much about me??”

I tried to explain how I had studied and done research at the library. “But you are so young!! You understand… what I do!” Blushing furiously, I stammered and tried to tell her how much pleasure her singing had brought to me.

She nodded, and “Thank you, thank you for coming to see me. You must come to Vienna sometime! I must go now, sorry, I have to be somewhere soon. Thank you, thank you for the beautiful article!”

We departed, and I did not walk, I floated out of there. Kitsch metaphor aside, meeting and receiving praise from Edita Gruberova, hearing her in person for the first time – Es ist ein Traum!

After we got home and mom dropped me off to my small, modest quarters on the Ann Arbor University of Michigan campus, I felt a sinking, depressive let-down. I had descended from my brief respite in operatic heaven back to the very ordinariness of earthly existence. I carried that night with me and continued collecting recordings and studying.

Next time: a bold and crazy idea!

Niel Rishoi is the author of Edita Gruberova: Ein Portrait, published in German, Japanese, and Slovak.

Comments