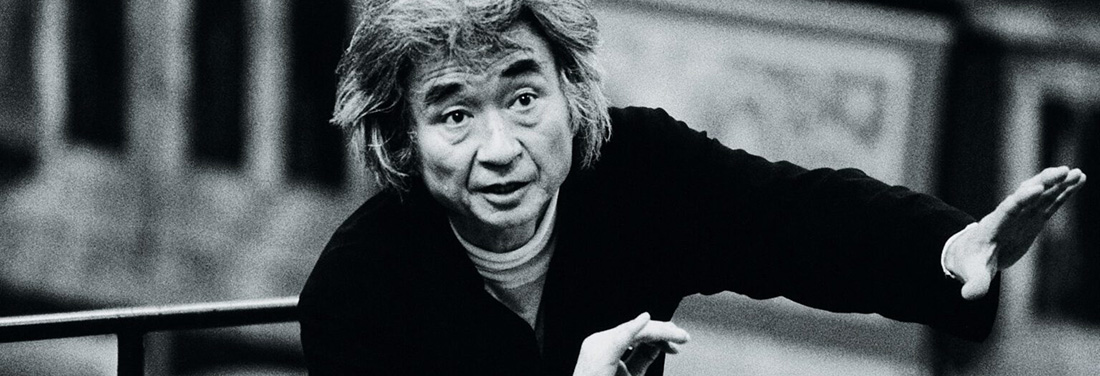

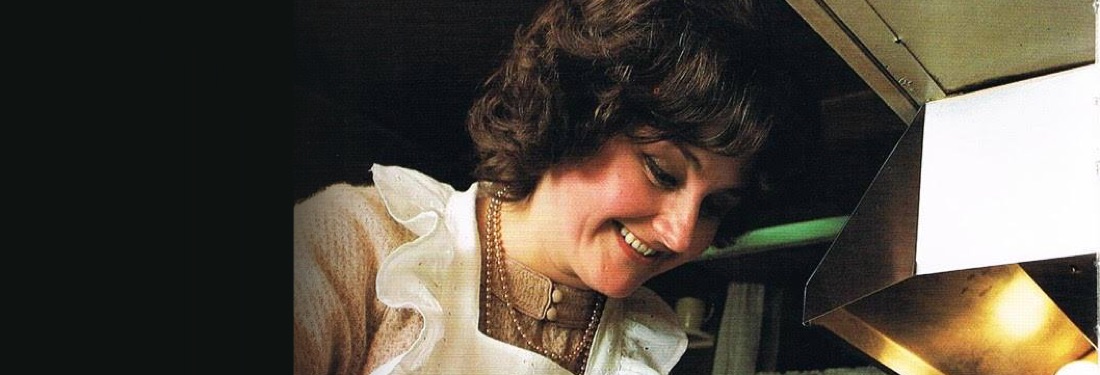

Then she took me down to the artist and staff commissary where we had lunch; there we spotted a very fetching, smiling Aprile Millo.

One of the most enlightening evenings was spent at the Czech restaurant on 75th street, Vašata. The entire dinner was spent discussing conductors. For Kleiber and Harnoncourt she reserved special praise, but for several of them she worked with—such as Sawallisch, Masur—there was affection and keen insights into their styles.

As I asked about each one by name, she described them by often taking on their manner of expression and the way they spoke. Edita was an outstanding mimic, yet it was all absent of malice or derision. There was one conductor, though, quite legendarily renowned, who made a living hell for all the artists in a new production at a prestigious opera house. Two of Edita’s colleagues I later spoke with both concurred and said it was the “worst,” most “humiliating” and “debilitating” experience of their careers.

A month of long rehearsal days commenced, with the artists being made to hang around even when their services were not needed, the conductor condescending and abrupt, driving the singers mercilessly. By the time of the premiere, Edita said forcefully, “We were dead.” Yet she still, conversely, praised this conductor’s musical talents, explaining that he ran the artists through individually on the piano, with intensive coaching. When she had problems with a few conductors she clashed with, I asked her, what was the main cause? “Their egos, thinking they were much greater than they are, and being like they hate working with singers.”

After that last performance of I puritani, which was the night before both our departures from New York City, we walked over to a modest diner for a late-night meal. After we were seated, our waitress began rattling off the daily specials and sides, in a voice resembling something on the order of Minnie Mouse with an impenetrable Bronx accent. Edita’s eyes spun around in disbelief, and, staring at me, whispered, “Niel, I can’t understand a word she is saying.”

I asked the waitress to give us a minute. When she was out of earshot, Edita looked at me in amazement and hissed, under her breath, “What was she saying??,” then proceeded to do a perfect imitation of how the waitress spoke, expressions and all. It was so comically accurate that I had to cover my mouth to avoid howling with laughter, and the effort to suppress that made me laugh even harder, then harder still until tears came and me being sure my face was turning purple.

Edita continued, “What is this what she said ‘moshed partater’?” I tried to explain, using a stirring motion, and then she exclaimed, “Oh, you mean puréed potatoes?” Yes, exactly, I replied. “Oh, yes, please!” She tucked into those moshed partaters with sheer delight.

After we ate, I walked Edita back to her rental apartment, in a building that looked like an Egyptian temple—“Here we are, back at my temple of Isis und Osiris,” she quipped. It was late, we were tired (New York City’s hustle-and-bustle promotes good sleep), and our goodbyes were swift—she took my hands, leaned forward, and I kissed her on the cheek, and Edita giggled, “Remember, Niel, like in Europe, one kiss on each side, ok? Ciao ciao!”

I made to go back to my room at the YMCA. I was lost in my screwy head with beatific contentment at the wonderful last 10 days. I was practically Gene Kellying it down Broadway.

However, it probably wasn’t a good idea that I neglected to be guarded and watchful in New York City after midnight. All of a sudden I was accosted by a greasy, dirty man with his hand in his powder-blue sweat jacket pocket, in a way that indicated he had a gun, but it could just as well have been a finger.

He motioned and mumbled to me, pointing to my binoculars in a case with a strap, to hand it over to him. Before I could react, he violently yanked the strap off my shoulder with such force, I lost my balance, slipped, and fell to the ground, ripping both my pants and knee, as the guy fled.

A couple of young women ran over and helped me up and asked if I were ok. I thanked them, and ran all the way back to the Y. I was shaken up and quite bruised of knee, but ok. The next morning, I couldn’t wait to get out of the city and back home to Ann Arbor.

The city, though, had one last “message” for me. As Shirley and I got into the cab that would take us to Port Authority, a pigeon shat on my head. The cab driver, seeing this, had a hard time keeping it together, but he immediately handed me some kleenex.

A day later, I called Edita to make sure she got home without any problems. She asked me the same. I told her of my incident. She was horrified, and urged me to have a doctor look at my knee, worried the dirty pavement would cause an infection.

Three days later, she called to check up on me, and was quite maternal in her concern.

That was Edita.

Comments