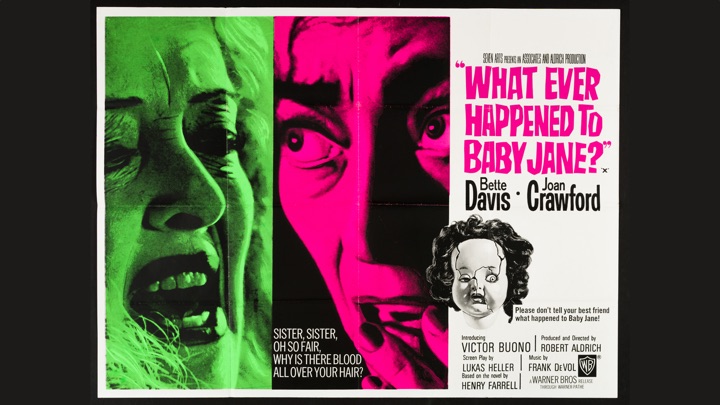

Cameron Kelsall: Although Hush…Hush, Sweet Charlotte contains more than a few interesting performances and some particular, peculiar insights—as we discussed last week—the balance largely lands in the camp column. But I agree that Baby Jane (as we’ll call it for brevity’s sake) is much smarter, and more sly, in nearly every respect. It’s interesting that both films are almost exactly the same length, two hours and 13 minutes, yet Baby Jane almost never drags, whereas Charlotte could easily lose up to an hour without any depreciation. The film keeps the viewer engaged, enraged, enthralled, embarrassed and titillated at every turn. A good deal of that is due to the stars—Bette Davis, our current idée fixe, and Joan Crawford, who needs no introduction—who translated their chilly personal relationship into one of the most captivating and terrifying sibling dynamics ever put on screen. But the movie itself excels in so many areas that I hope we can consider, from performance to aesthetics, and on its strength alone, I would rank Aldrich as an unjustly overlooked auteurist.

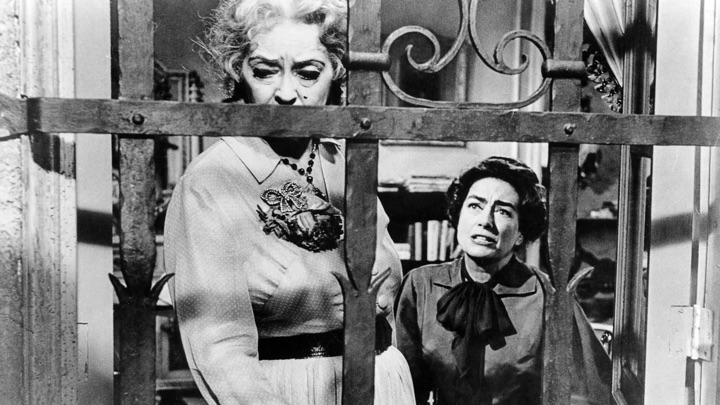

CK: As we dig deeper into the Davis oeuvre, I am continually impressed by her level of commitment and, given the reputation that has been applied to her post-mortem, her general good taste. Every gay man and/or drag queen can crow the immortal “But’cha are, Blanche!” line or imitate Baby Jane’s shrieking cackle, but those elements are only little dashes of a performance that is surprisingly vulnerable and richly detailed. And her relatively emotional work plays nicely against Crawford’s rather staid, serious performance. Whereas Davis allows herself to be fully seen in all of Baby Jane’s physical grotesquerie—impressive when you consider she made the film right after originating the sexpot role of Maxine in Night of the Iguana—Crawford’s neatly preserved appearance makes a strong contrast. Even when Blanche Hudson is at her most vulnerable, she appears attractive and collected; even when Baby Jane is at her most abusive and unhinged, she never sinks to full monstrosity.

CK: Great as Davis and Crawford are here, they’re not the whole show. The picture brims with colorful supporting performances, and in some ways, you could look at Aldrich as a precursor to directors like Robert Altman or Paul Thomas Anderson who really put a lot of stock into building out the entire world of the film, and making sure even the smallest part is cast with someone unique and memorable. (It’s worth noting that Aldrich, like Altman or Anderson or even the aforementioned Ryan Murphy, tended to use the same actors in multiple projects.) Of course, the takeaway supporting performance here is Victor Buono’s Oscar-nominated turn as Edwin Flagg, the oily accompanist who stumbles into Baby Jane’s frenetic fantasia. But there are so many great little roles, like Maidie Norman as Blanche’s devoted servant, Elvira, or Anna Lee as Mrs. Bates, the busybody from next door. (And of course—Davis’ own offspring, B. D. Merrill, is a hoot as Mrs. Bates’ snippy teenage daughter.)

CK: The framing of Norman’s character and her relationship to Blanche is of a piece with what I think makes Aldrich such an interesting director. Like Nicholas Ray or Douglas Sirk, he’s working within the constraints of a genre, but also subverting expectations throughout. He’s also unafraid to move away from sheer horror into something more psychologically disturbing. I’m always left reeling by the strangeness of the final scene, as Baby Jane, about to be apprehended by the police for Elvira’s murder, loses herself in reverie, imagining the crowding onlookers as an adoring audience. Davis’s committed performance and Ernest Haller’s unsettling cinematography create such an unusual sense of unease. It feels almost experimental.

CK: Feud, at least, had some snappy performances—I can never get enough Jackie Hoffman—and a generally high bitchiness quotient. A true lack of grandeur, however, is what you get in the woebegone television remake from the early ‘90s featuring real-life sisters Vanessa and Lynn Redgrave. It’s available to stream through Amazon Prime, and we said we’d try to watch it before writing. I only made it through about 45 minutes. You?

DF: I stuck it out for the full 90 minutes—maybe the longest hour and a half of my life. Woo boy. I suppose one could say of it that if anyone ever questions why Aldrich’s Baby Jane is such a beloved piece of work, this crass, clueless reboot will illustrate the difference, point for point. Surely, there was never a movie where a remake is more wrong-headed, but I will say the Redgrave version had one promising idea at its center, that in a way speaks to what I was talking about with movie mythology. Here, the world of Baby Jane is re-situated with Los Angeles’s fringe movie-lover culture. That should have been interesting, but instead it goes for virtually nothing. Both Redgraves are, of course, brilliantly gifted actors, but you sure wouldn’t know it from this. And the production values—despite this having been made by a major television studio—are unbelievably tawdry. A lot of it looks like bottom-shelf porn, minus the sex.

CK: All I can add is that while Davis and Crawford both give multifaceted performances, the Redgraves here indulge in what I think of as their worst qualities—Vanessa’s beatific saintliness and Lynn’s crass overindulgence. I’ve seen them both brilliant; I’ve never seen either worse.

DF: I wonder if anyone thought to ask Corin Redgrave to play the reworked and renamed Buono character? Instead, that’s played here by John Glover, who is creepy but not very interesting. Oh, well. So, I guess now we know what happened to poor Baby Jane. But Cameron, shall we agree to return when we get the next remake with Demi Lovato and Madison De La Garza?

CK: It’s only a matter of time, isn’t it? Till then, we’re going to take a brief detour away from Davis and into Crawford territory next week, with Johnny Guitar.

Comments