Adriel

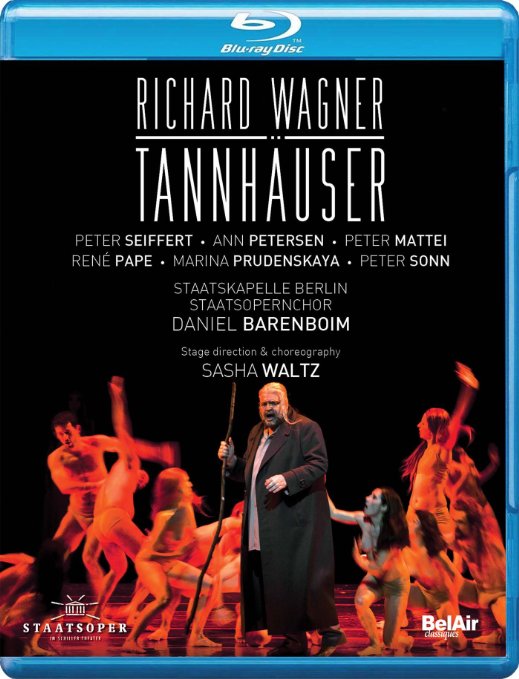

Richard Wagner viewed dance as an essential element of art, though he used it sparingly in his operas.

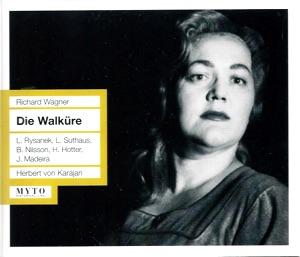

Myto’s transfer of Herbert von Karajan’s star-bedecked 1958 Die Walküre from La Scala gives collectors on a budget access to one of the legendary performances committed to tape.

Live recordings of Hans Knappertsbusch conducting Parsifal seem to proliferate like stairways in M.C. Escher prints.

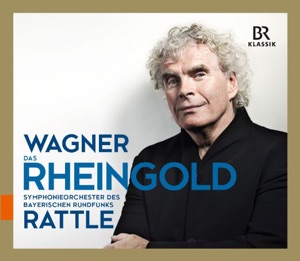

Das Rheingold is the outlier among the Ring operas, an ensemble work with a fast-shifting plot, animated dialogue, fewer set pieces and less character development.

Anja Silja staked a claim as a leading Senta of her era with a series of searing performances of Der Fliegende Holländer while in her early twenties.

“Disciplined and intelligent.”

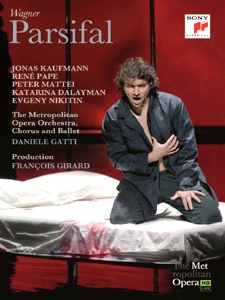

Contemporary stagings of Parsifal tend to be spare, abstract affairs scrubbed of religious associations, knights in armor and, sometimes, a grail.

If works like Salome and Erwartung defined modernism in the first decades of the 20th century, Die Tote Stadt and Palestrina represented the regressive avant garde.

Herbert von Karajan once said listening to some of his old recordings made him envy painters who could simply burn the pictures they disliked.

When Richard Wagner reached into the past and revised Gluck’s Iphigénie en Aulide, he went beyond the accepted boundaries of tinkering and more or less created a new work that’s fomented aesthetic debates ever since.

One of the things that made François Girard’s 2013 production of Parsifal at the Met so compelling was the way he tried to make the tale of suffering and temptation relevant to a contemporary audience.

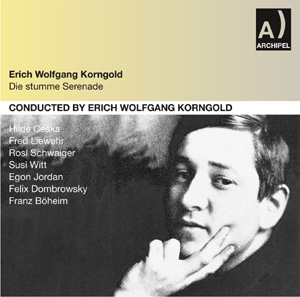

Vienna never really forgave Erich Wolfgang Korngold for going to work in the movies.

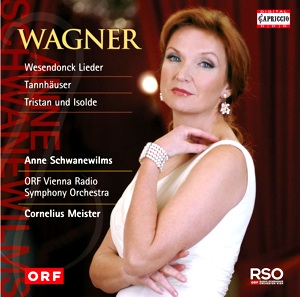

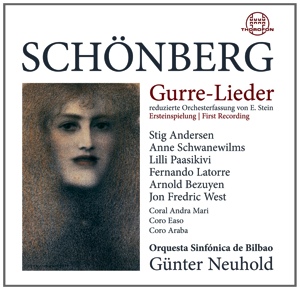

To some, Anne Schwanewilms will always be the soprano in the slinky black dress who replaced Deborah Voigt at Covent Garden a decade ago.

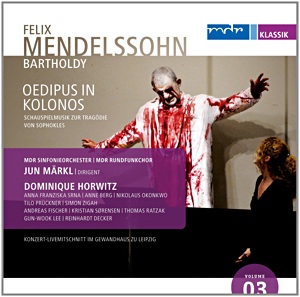

His 75-minute setting of Oedipus in Kolonos, heard in a live 2009 performance on MDR Klassik, illustrates how Mendelssohn tried to link ancient forms with Romantic-era sensibilities by fashioning harmonically adventurous chorales and believable characters instead of abstract musical representations of mythical figures.

With orchestral and choral forces that could outnumber a small European village, Arnold Schoenberg’s Gurre-Lieder is a composition designed to overwhelm.

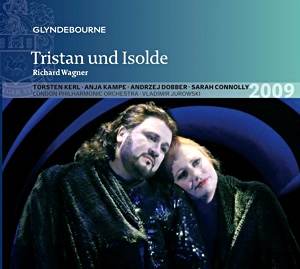

The finer performances of Tristan und Isolde have a way of sounding like a four-hour improvisation, the fruit of a single moment of inspiration that makes one forget how emotionally manipulative and painstakingly crafted the music really is.

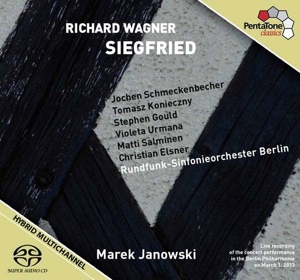

Marek Janowski’s survey of Wagner operas on PentaTone so convincingly captures the pulse and dramatic flow of many of the works that the music-making at times sounds almost effortless.

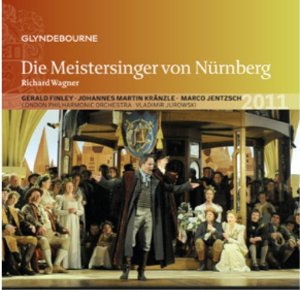

Beneath the pageantry, the paeans to German art and the self-referential allusions to the creative process, Die Meistersinger is a story about a community and human qualities like love, friendship, envy and hatred.

The abrupt withdrawal of Katharina Wagner from an abridged seven-hour Ring cycle she was to direct at the Teatro Colon last year prompted no shortage of scorn and Schadenfreude.

The curious things about accepted wisdom is that sometimes it’s correct.

Marek Janowski’s second recorded Ring cycle began on an off note, with a Rheingold that was fleet and lucid but failed to impress in the important musical moments.

The 1965 season was a time of big changes at the Vienna State Opera.

Between Fidelio and Der Freischutz there was “Romantische Oper,” a type of musical drama descended from medieval mystery plays in which ghosts, gnomes and other “invisibles” get entangled in the lives of unsuspecting people.

Could Marek Janowski do for Wagner what the early music movement did for the Baroque and Classical repertory?