Beneath the pageantry, the paeans to German art and the self-referential allusions to the creative process, Die Meistersinger is a story about a community and human qualities like love, friendship, envy and hatred. One can get absorbed in Wagner’s multilayered portrait of medieval Protestant life or just connect with the straightforward narrative about two young lovers and the older man trying to help them.

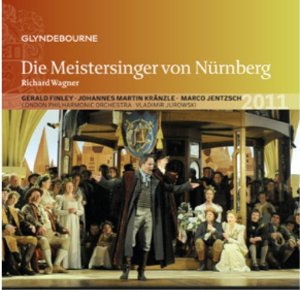

Director David McVicar emphasized the more intimate approach when he conceived a 2011 production for Glyndebourne that marked only the second full staging of a Wagner work on the Sussex Downs. Though the snug confines of a 1,200-seat theater may have limited some of the creative team’s options, the concept placed extra importance on nuanced characterizations and chamber music-like effects that summon the spirit of a midsummer’s eve.

A four-CD set on the festival label culled from several performances in the run has a pleasing nervous energy, with an emphasis on folk-like qualities and bright textures that Wagner wove into the townspeople’s banter and personal tension in the artistic quarrels between Hans Sachs and Beckmesser. It’s a less sumptuous, more believable take that could benefit from a little more dramatic depth and stronger casting in some of the leads.

Glyndebourne’s then-Music Director Vladimir Jurowski said at the time that performing this opera for a predominantly English audience allowed the festival to downplay the libretto’s nationalistic sentiments and to emphasize its portrayal of human foibles and sense of collective experience. Abstaining from the grand operatic style also makes one appreciate the carefully thought-out musical architecture, and Wagner’s savvy manipulation of the audience, accomplished through devices such as the multiple repetitions of motifs in the Preislied.

The undisputed star here is baritone Gerald Finley, whose Sachs comes off as younger and more tightly wound that one is accustomed to hearing. There’s an impatient, angry aspect to the great Act 3 monologue “Wahn! Wahn! Überall Wahn!” and convincing brusqueness when the cobbler tells Eva she would be better with a younger man, then bitterly laments his empty life. Finley is most convincing, however, in understated moments that reveal a poetic core to the character that make you believe he could actually win the girl. “Mein Freund, in holder Jugendzeit” has the glowing qualities of the prize song, and the brief pauses he injects in the dialogues with Walther convey an added degree of realism.

Finley’s rich characterization is matched by Johannes Martin Kränzle’s old-fashioned, comedic Beckmesser, who’s more competitive and self-important than malicious. Another youngish baritone one might not immediately associate with Wagner, Kränzle uses his nicely focused voice to good effect in the Act 2 serenade and manages to convey ironic humor without turning the town clerk into a cartoon. His interactions with the mastersingers in the vigorous first act serve as a reminder that this character was never intended to be a talentless pedant.

The other principals don’t quite scale such heights. Tenor Marco Jentzsch is cautious and lacks the requisite bloom to make Walther’s music really soar. Soprano Anna Gabler has a pleasant lyric voice but makes little impression vocally or dramatically in the scenes with Sachs or in the Act 3 quintet. Far stronger is mezzo Michaela Selinger, a particularly assertive Magdalena, who has some fun exchanges with the energetic David of tenor Topi Lehtipuu. The Pogner, bass Alastair Miles, boasts perhaps the most imposing voice in the cast and delivers a fine account of “Das schöne fest, Johannestag.”

Jurowski and the London Philharmonic take a little time to heat up but by Act 2 deliver a sparkling accompaniment that exudes a sense of romantic innocence and sends lovely instrumental solos floating out of the pit. Jurowski attentively supports the younger, lighter voices without sacrificing too much pomp and drama. Unfortunately, the Act 3 chorus sounds a few guilds short of what Wagner had in mind (no doubt a function of the stage dimensions) and doesn’t generate the requisite flood of sound across the meadow and Pegnitz River.

The set’s sonics are generally clean and well-balanced, but there’s a distracting amount of stage noise during the crowd scenes. The attractive program book includes a nice essay about Wagner, Glyndebourne and festival founder John Christie’s vision of an English Bayreuth, along with photos of the cast and production.

Though a Meistersinger so keyed around personal interactions is probably better seen in person or on video than simply heard, this volume could provide an attractive alternative to much-loved, more imposing renditions by Solti, Jochum or Karajan without straying from the essence of the work.

Comments