Elisabeth Vigée-LeBrun, in her memoirs of the decade before the French Revolution broke out, tells the story of four elegant young bucks addicted to opera. So devoted were they, that one night they stationed a carriage near the opera house in Paris, and, when the performance concluded, raced from the house and hopped aboard the conveyance, setting off at top speed to the north. With several changes of horse but no other pause, they rode all night and all day — remember what the roads were like in France before Macadam and Michelin! — to arrive at the opera house in Brussels the following evening, just in time for the performance. (What opera? Who sang? She doesn’t say.) And when it was over, what did they do? You guessed it — they hopped into the coach (the horses and the drivers having had a good meal and a lie-down), and back they went, instanter, southwards this time, over the Austrian border and so to Paris. They got to the theater just in time — another box awaited them, and another performance! How did they manage? (Bottoms were tougher in those days.)

What this tale has always said to me (though Bessie V-L doesn’t mention the matter) is that opera queens are as old as opera. Which is just how I feel these days. As old as opera.

But the thing is, in our long, long history in the shadows, despised and rejected and clandestine, no one in the serious and discriminating heights of opera-commentary had ever been willing to acknowledge that the gay perspective was worthy of notice, brought something serious and learned and passionate to discussion of the art. The serious commentators — though gay themselves, often enough — would seldom give us the time of day. For some centuries that was understandable, considering the prejudices of society in general.

But society has made a nice start at outgrowing those. And with drag and the more eccentric forms of sexuality now in all the headlines and the more reasonable schools, why should that disdain be permitted to linger?

And by coincidence — but it was NOT a coincidence — James Jorden arrived in New York about this time from Lake Charles, Louisiana (“the desert of New Orleans,” he would describe it), wishing to make his mark on the profession of opera production. Only to find himself underqualified and underconnected.

While passing the time till Patrice Chereau came calling, our JJ started to “publish” — xerox, actually — a home-made zine of opera crit, opera satire, opera discussion, put a pink cover on it, gave himself a nom de plume (he already had the attitude and wit to go with it) and began to hand it out to unwitting Met patrons. We all know where that led.

Success, if not financial, soon followed. He was filling a need — for all of us (not just gay men by any means) who believed opera was important, was significant, had things to say (or sing) about the modern world, in modern or old-fashioned language. And it was time for that, as we know because everyone in the rarefied world of opera soon knew, if not who La Cieca was, then certainly what Parterre Box was. The opinions of JJ’s stable of writers (where I chewed much cud for, gran Dio!, twenty-five years, I think the Parterre record) were devoured and sought out from coast to coast and beyond.

I was handed a copy of the magazine by an outrageously got-up person of multiplex sexuality (not JJ) one intermission at the Met in the 90s. Soon I was joining JJ for the gatherings to collate pages. And contributing humorous asides. Actual critiques were requested once the zine made the leap to web page.

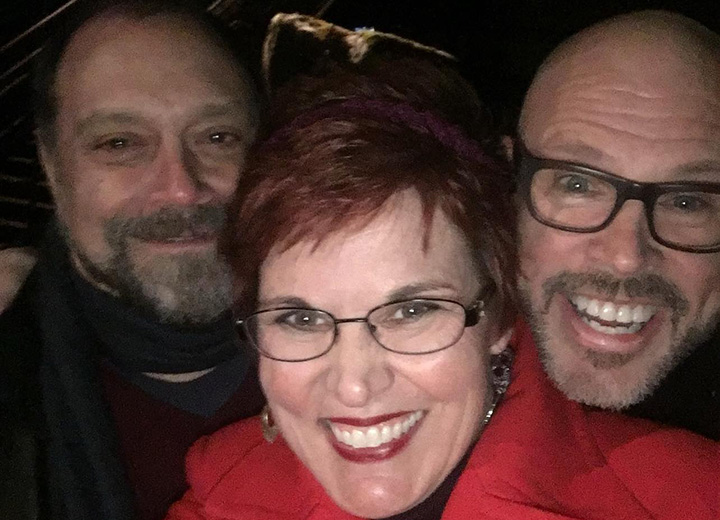

Opera companies over a vast geographical area soon were gracious about providing press seats for Parterre. Seattle! Chicago! Boston! Vienna! Palermo! When I got a job in the Archives of the Met, my boss, Bob Tuggle, wanted to know about James — was he a lonely, unattractive soul living only through what he saw on stage, or was he handsome and interactive? (The latter.) And did he really have a tattoo of Callas on his shoulder blade? (Yes, but I never saw it.) When Jimmy McCourt’s divine Mawrdew Czgowchwz was republished by NYbooks, Jimmy asked me if I knew James, could introduce him and arrange an interview. I knew James would be thrilled, and the interview proved luscious.

An opera-loving lady of great discernment who read Parterre daily told me I was the nicest, least vicious of its commentators — which is kind of like being the least outrageously dressed at the disco, isn’t it? I’m certainly the first who insisted on using his own name to sign articles — Parterre was too notorious for aliases except in the comments. Although I miss being Hans Lick and Victoria de las Vegas. And I was as tickled by Enzo Bordello and Decaffarelli and Batty Masetto as anybody else. (Other terrific puns will occur to you.)

And on a personal level, James applied to me for such chores as cat-sitting, watching obscure Joan Crawford films together (his favorite was A Woman’s Face; mine, Sudden Fear) and an evening of video Lohengrins. And long conversations full of theatrical anecdotery.

But I noticed that, flashy as he was, witty to any measure, and up on the insides and outsides of current opera staging, I never learned very much about James Jorden. He was very private. There are different ways to be private — silence did not appeal to him (unless an intermezzo was being played — and, too often, staged); his conversation was all flash and fireworks and darting barbs.

I was always waiting for him to turn on me and bar me from the page, as he did so many. Somehow I escaped. Nor did he ever — ever — insist that I agree with his taste. With all his writers: he might correct grammar or spelling or my tendency to RUN ON, but opinions were sacred to the writer.

But what went on behind the vivid facade? That I never knew. His emotional life (and how the hell he financed things) remained secret. I believe all of us are entitled to our own levels of privacy. I knew JJ worshiped Scotto and Netrebko — I did not, but so what? — and detested Fleming’s excesses — as did I.

Only since his death have I realized that, though I still offered and received occasions to review this or that, or contribute an article, I had not seen JJ face to face since before the pandemic. I had no idea what was going on. He no longer posted his running progress on Facebook — was he still in shape? I knew he had a new apartment in Sunnyside, but I never saw it. I just knew the NYTimes had raved about him and his web site. And new writers were showing up on it. All seemed to be moving according to plan.

He went his own way, and haven’t we all been rewarded to be in his audience? I think he will be remembered as a revolutionary firebrand with no blood on his hands. Like La Cieca, another body in the Orfana Canal. O monumento! Opera goes on.

Comments