Mozart tinkered with the Messiah. Mendelssohn adapted choral works by both Handel and Bach. But when Richard Wagner reached into the past and revised Gluck’s Iphigénie en Aulide, he went beyond the accepted boundaries of tinkering and more or less created a new work that’s fomented aesthetic debates ever since.

Wagner saw the tale of fatherly love pitted against the public will as a test bed for his notions about new, plot-driven musical drama. Putting aside the partly completed Lohengrin in the winter of 1846-1847, he translated the French libretto into German, cut most of the ballet music, expanded the orchestration and added preludes and interludes to connect scenes and more tightly focus the action on the title character.

He also dispensed with the dea ex machina ending Gluck himself added for the Paris stage after the work’s 1774 premiere, instead sending the heroine off as a transfigured figure to an unknown land, more in the spirit of Euripides’ play.

Though some early music specialists still blanch at the interventions, Wagner’s edition has remained part of the repertory in Germany, where it provided a vehicle for Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, Thomas Stewart and Anna Moffo, among others.

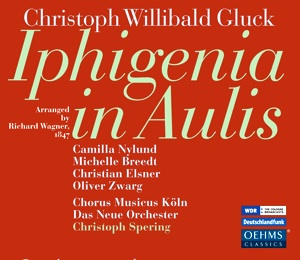

A new Oehms Classics release from Christoph Spering and Das Neue Orchester, issued for the tricentennial of Gluck’s birth, shows how the taut, through-composed format effectively links the arias and choruses to frame the Ring-like predicament facing the Mycenean King Agamemnon, who must decide whether to accede to demands he sacrifice his daughter to assure the crossing of the fleet to Troy.

The musical results are more scattershot. Spering tunes his orchestra down to 437 hertz and tries to approximate what he thinks Wagner could have accomplished sonically with mid-19th century forces—had he sweated the details.

In the accompanying program book, the conductor states that Wagner hewed too closely to Gluck’s tastes and sacrificed some of the aural possibilities for dramatic content, adding that he felt compelled to “liberate” the sound from the “accumulated slag” of interpretive history. This means overpainting the overpainting, an exercise that’s daring one moment, excessive the next (unless you’re a fan of three-part trombone writing) and leaves one generally whipsawed between musical styles.

The thicker textures from Wagner’s augmented winds and doubled violas create a soundscape not unlike Beethoven’s but with harmony that is unmistakably Gluck’s. Rewritten string passages designed to intensify the drama and sustain the Romantic line tend to wash away the original’s courtly grace. Strident tuttis in the overture and Act 2 march may send purists running back to Gluck’s own handiwork, memorably recorded by John Eliot Gardiner with Jose van Dam in the early 1990s.

The vocal talent is also pumped up to Wagnerian proportions. Finnish soprano Camilla Nylund is an icily elegant Iphigenia, agile but a touch tense in the middle act showpiece “Bald von Fürchten und bald von Hoffen” and generally sounding more comfortable with the hybrid musical style than the other principals. Her decision to do herself in for the good of the public is perhaps the most affecting moment in a performance that often sounds effortful.

The full-throated German tenor Christian Elsner blusters his way through the difficult role of the warrior Achilles, Iphigenia’s betrothed, sounding too declamatory in passages that require lyric agility, such as the Act 2 trio with Iphigenia and Klytämnestra.

South African mezzo Michelle Breedt lacks the supple voice for some of Klytämnestra’s passagework and also is a bit one dimensional, dramatically speaking. Worse, her careful diction reveals how the loud German consonants don’t always mesh the work’s longer melodic lines.

Baritone Oliver Zwarg nicely captures Agamemnon’s anguish in big aria “Weh’ mir! Welch ein Beginnen” at the conclusion of Act 2 but lacks the legato and steady top to nail more exposed numbers such as Act 1’s “Kann vom Vater die Göttin fordern.”

Bass-baritone Raimund Nolte makes a favorable impression as the seer Kalchas, as does soprano Mirjam Engel, who as Artemis saves the day by proclaiming the gods have been reconciled by Agamemnon’s willingness to make a sacrifice.

The Neue Orchester and Chorus Musicus Köln, both founded by Spering some three decades ago, are sharp and authoritative throughout, with the chorus sounding suitably bloodthirsty calling for Iphigenia’s head at the beginning of the final act.

But the committed ensemble can’t resolve the messy ending, a miraculous intervention that doesn’t stack up to the one Wagner would conjure in Tannhäuser, that finds the composer unable to reconcile classical grandeur with his own narcissistic ambitions. A bonus cut presents the overture as a stand-alone concert piece.

Wagner acolytes and the musicologically inclined will find plenty to chew over, especially in sections that illustrate quite vividly how the Baroque reformer guided the Romantic master’s musical development. Others will find the adaptation an ungainly musical curiosity that’s hard to embrace and harder still to objectively judge.

Comments