With orchestral and choral forces that could outnumber a small European village, Arnold Schoenberg’s Gurre-Lieder is a composition designed to overwhelm. The young composer was intent on cashing in on the pre-World War 1 fad for gigantism that spawned such works Mahler’s Eighth Symphony and on exploring a full palette of human emotions and natural wonders in a single evening. His fin-de-siècle oratorio deploys upward of 300 performers and contains a kitchen sink of effects, including trombone glissandi, percussion with chains and a surreal spoken “melodrama” about the transformative Nordic wind.

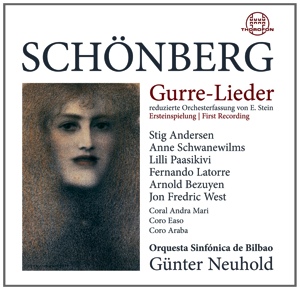

The bloat is the only thing shallow about the work, something Schoenberg understood when he sanctioned a version for conventional-sized forces nine years after the 1913 premiere to get wider play. Recorded for the first time by Günter Neuhold and the Orquesta Sinfónica de Bilbao on Thorofon, this three-quarter scale edition dials down the dramatic spectacle to better reveal the intriguing broth of fleeting moods and visions drawn from the 19th century Danish poems by Jens Peter Jacobsen that Schoenberg set to music.

While you miss the wash of instrumental colors and lush chromaticism, the leaner textures and more clearly defined musical lines illustrate how a composer in his 20’s simultaneously embraced Romantic tradition and rebelled against it by exploring new means of expression.

The work’s mythical tale of forbidden, unattainable love invites obvious comparisons to Tristan und Isolde, though some have noted it could pass for a parody of Wagner and his notions of redemption. The story revolves around the medieval King Waldemar, his paramour Tove and the jealous Queen Helwig, who has Tove killed (in one telling of the legend, by roasting her in a locked sauna).

The emotionally shattered king summons a pack of ghostly henchmen to help him search for an eternal reunion—a nightmare that ends with the crowing of a cock and the narrator describing how nature sweeps away tragedy with a new day filled with blossoming flowers, prancing horses and dancing crickets. The Nietzschean faith in eternal return makes the piece similar in spirit to Das Lied von der Erde.

For the reduced version, Schoenberg turned to his one-time pupil Erwin Stein to thin out the orchestration, transpose some high-lying choral parts down an octave and alter polyphonic passages that he no longer believed were necessary. The changes in some ways defeat the composer’s goal of giving each of the work’s three sections its own distinct sound but tidy up cacophonous moments such as the end of Tove’s second song, “Steme jubeln,” when blaring horns, trombones and trumpets collide with timpani and bass drum thwacks.

By preserving an orchestra of about 100 and a battery of choirs, Stein, who also did a slimmed-down adaptation of Wozzeck, left enough sumptuous sound to make moments such as the Straussian conclusion of Waldemar’s “Ross! Mein Ross!” exhilarating.

Danish tenor Stig Andersen has made Waldemar something of a calling card, recording the original version with Esa Pekka Salonen and Mariss Janssons. More a big-voiced lyric tenor than a true heldentenor, he’s at his finest in the first section’s love songs, using tasteful phrasing and pleasant soft singing to describe the peaceful twilight in “Nun dämpft die Dämm’rung.” The dramatic passages are more paint-by-the-numbers: Andersen could summon more grief and rage cursing God in the critical scene after he learns of Tove’s death, when the tenor should sound one breath away from spontaneous combustion as the music turns more tonally unstable.

Soprano Anne Schwanewilms takes a vigorous, at times even hard-edged approach to Tove’s music, with a strong connection to the text and a penetrating tone that easily slices through the orchestra. The emotional peak of the first section, “Nun sag ich dir zum ersten Mal,” was by turns tender and dramatic, with a steely edge.

Finnish mezzo Lilli Paasikivi’s Wood-Dove is dignified and otherwordly, delivering the news of Tove’s death with heavy, dark tones that are a highlight of the performance. In the smaller roles in the final section, bass-baritone Fernando Latorre is earthy and pointed as the terrified peasant who describes Waldemar’s hunt with the horde of spirits. Tenor Arnold Bezuyen is convincingly nutty as Klaus-Narr, the sarcastic court jester, who reveals the king’s harsh and unjust side and is forced to join Waldemar’s creepy night ride. Jon Frederic West intones the speaker’s lines in a sprechstimme that anticipates the composer’s Pierrot Lunaire.

Most impressive are the Neuhold and the Bilbao orchestral forces, who deliver a confident account of the unfamiliar score. Because much of the vocal accompaniment comes from small clusters of instruments, there’s a premium on strong ensemble playing and chamber music-like textures. The prelude has a Wagnerian shimmer, and the interlude leading into the spoken melodrama is nicely balanced with burbling woodwinds, harps and celesta. The grotesque accompaniment to the jester’s song has just the right amount of bite.

Though the three local Basque choirs enlisted for the performance don’t exactly shake the earth in the concluding C major paean to the sun, they keep the dense music moving forward and bring out Schoenberg’s skilled use of counterpoint. The sound is consistently bright and delineated.

Those who consider Gurre-Lieder an important specimen of early 20th century modernism will probably find manifold rewards in the Stein edition, even if it’s not absolutely essential to a recording collection. Listeners attracted to the original’s raw power and grandeur may come away disappointed by the way the miniature demonstrates this work has more head than heart.

Comments