If works like Salome and Erwartung defined modernism in the first decades of the 20th century, Die Tote Stadt and Palestrina represented the regressive avant garde. Though they had tormented protagonists, themes of death and other ingredients for a frenzied geschrei, neither could break free of the Romantic era’s pull, instead inhabiting a netherworld that’s sometimes described as “post-Wagnerian” or “Straussian.”

Repressed during the Nazi era, both re-emerged after World War II in German-speaking countries, where they were admired for their brainy sincerity and just maybe, some of the old-fangled overtones. A pair of 1950s performances now available on CD would provide the mortar for later stagings by provocative directors such as Götz Friedrich, Günter Krämer and Nikolaus Lehnhoff that nudged the works closer to the mainstream repertoire.

Erich Wolfgang Korngold’s youthful psychodrama is the more listenable of the pair and emerges in surprisingly good sound in a 1952 Bavarian Radio performance on Myto. The tale has often been compared to Hitchcock’s Vertigo: Paul, a grieving widower, sees the doppelgänger of his dead wife as her reincarnation, pursues her, then, riddled with guilt, strangles her with a plait of the late missus’ hair. Except it’s all a dream. Once awakened, the hero grasps the need to let go of the past and departs his “temple of memories.”

Inspired by Georges Rodenbach’s gloomy symbolist novel Bruges-la-Morte, the 1920 opera’s themes of loss and reconcilement surely resonated with audiences traumatized by the Great War before the Third Reich designated it degenerate. It’s held back by an overripe, at times kitschy score and the heavy-handed influence of the composer’s father, the conservative Viennese music critic Julius Korngold, who wrote the libretto under a pseudonym. Successful performances manage to alternate between Paul’s jittery dream world and his poignant longing for a time gone by.

Conductor Fritz Lehmann, an early advocate of historically informed performance practice, does well in the latter respect, taking care to bring out the sweetly melancholy quality of the opera’s most famous number, “Glück das mir verblieb,” and the lilt of the “Pierrot Lied” that briefly suspends action midway through the work. While one admires the balance and clarity, the reading doesn’t do justice to Korngold’s vivid orchestral colorations and is simply too foursquare for such unhinged, hallucinatory goings-on. The truncated edition for the performance merges Acts 1 and 2 and omits the Act 3 prelude.

Tenor Karl Friedrich, a Viennese favorite from the 1930s and 1940s sometimes compared to Richard Tauber, ably handles Paul’s punishing tessitura and manages to sound robust and unforced when the orchestration is thickest, even if he isn’t the most accomplished singing actor. As Marietta, soprano Maud Cunitz’s overtaxed upper register suggests a shrewish spouse more than a temptress and cuts through the middle act’s picnic scene like a migraine. The remainder of the cast features capable, if not especially memorable, contributions from Hans Braun as Fritz the Pierrot, Benno Kusche as Frank and Lilian Beningsen as Brigitta.

Myto’s minimalist packaging provides only the cast and track list, which won’t help first-time listeners or non-German speakers. The sound transfer is quite good, however, with a minimum of ambient noise and decent balance between the large orchestra and the stage. Though fans of the opera may find it an essential buy, the release is no threat to dislodge Erich Leinsdorf’s RCA release with Rene Kollo, Carol Neblett and Hermann Prey as the best option on disc.

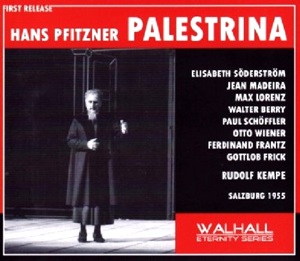

Palestrina, from 1917, is a thicker nut to crack and is heard in a boxy-sounding 1955 Salzburg Festival performance on Walhall

. Hans Pfitzner, an ardent nationalist and Nazi toady who still managed to get on the wrong side of Hitler, freely adapted the 16th century composer’s efforts to save polyphonic music into an opera with strong suggestions—right down to the running time—of Die Meistersinger and Parsifal.

The plot revolves around Palestrina’s search for faith after his wife’s death and his struggle to rise to the challenge of writing a Mass great enough to stop counter-Reformationists from dialing back church music to the Gregorian chant. The hesitant, unsure protagonist is jolted back to life by a visit from ghosts of nine great past composers, visions of his late wife and an angelic choir that dictates the Mass so he can finish it in a single night.

That just covers the 101-minute first act, which moves at times like a subway with locked brakes and gets bogged down in extended musings on the importance of tradition and whinging about Palestrina’s empty spirit. The air is thick with melancholy, sometimes obscuring artful pairings of music and text and an advanced use of leitmotives.

Things perk up in the final two acts, when the ecclesiastic council’s arguments over musical style degenerate into a deadly riot, the Mass proves a hit and Palestrina is vindicated and proclaimed a savior of civilization. The opera ends on a suitably fatalistic note, with the composer staring longingly at a portrait of his late wife, then turning to play his organ, resigned to whatever comes next.

Rudolf Kempe and the Vienna Philharmonic dig into the three orchestral preludes that comprise some of the opera’s most inspired music but plod for stretches elsewhere, unable to maintain long spans of tension or wring inspiration from the brief bursts of melody. It’s never less than a sympathetic reading that darts among the dozens of motifs and tastefully underscores quotations from Palestrina’s own music, as well as Bach and some of Pfitzner’s other works.

The heldentenor Max Lorenz’s robust, open-throated delivery had frayed some by the time of this performance, but his Palestrina strikes a balance between resignation and defiance, unwilling to let his art be used to boost the church’s power. His nemesis is bass baritone Paul Schöffler, one of the greatest Hans Sachs on record, who brings power and great textual clarity to Cardinal Borromeo, the composer’s mercurial and ultimately chastened patron.

Other A-listers sprinkled through the huge cast include the excellent bass baritone Ferdinand Frantz as the cardinal legate Giovanni Morone and bass Gottlob Frick as a sonorous Pope Pius IV. Soprano Elisabeth Söderström and mezzo Jean Madeira excel in the trouser roles of Ighino, Palestrina’s son, and Silla, his musically forward-looking pupil.

The Salzburg sound transfer is quite rough, with distracting tape hiss, a few dropouts and a lack of tonal depth that seems to magnify Pfitzner’s fondness for midrange orchestral voicing. As with the Die Tote Stadt release, the single slip cast and track list will send listeners Googling for more source material to grasp this dialogue-driven work.

For a performance with such talent and commitment, one is struck by the way the drama just doesn’t live up to its lofty aspirations. Pfitzner’s focus on juxtaposing the solitary world of the artist with the brittle realm of politics—and on music’s transformative power—surely robbed his libretto of some needed character development. And Kempe and the singers’ careful respect for what was probably unfamiliar material accentuates the ascetic, suspended qualities of the music. It’s enough to give you the sense of looking at a bug in amber.

It’s hard to say whether that would have upset the composer.

Comments