Post-book, as the soprano’s career flourished into the 21st century, I was not done learning about Edita and La Gruberova; the years and decades following provided new revelations into her art, among many other things.

In 2000, after I had been hooked up to the internet, I joined a few online opera discussion groups.

In the four years between the publication of my book until then, I had had very minimal contact with other aficionados of opera, apart from a few colleagues I met, mainly through the publication I wrote for, The Opera Quarterly.

In these groups I encountered quite an illustrious number of seasoned, long-time opera-goers, other critics, singers, agents, and musicians, from all over the world. I made several friends, who remain so to this day, who were also fans of Edita; and a few who were not – but they weren’t obnoxious about it. One of my earliest friends associated with opera, Richard LeSueur, is an art song and repertoire researcher; among his clients were his University of Michigan friend Jessye Norman, as well as Arleen Augér, Renée Fleming and Cecilia Bartoli.

Richard laid down many pointers and insights that lead to more intensive studies: he came closest to being an early, crucial mentor-figure. These friends gave me invaluable, constructive criticism about singing that did not always accord with my own views, and therefore provided needed counterbalance that caused me to analyze and study harder, as well as face truths about the object of my admiration.

But it was Edita’s severest critics and detractors from whom I learned most. In many instances the hard way, but that all served its purpose in the long run. There was a lot of nastiness, but nastiness can often be immensely informative and unwittingly revealing.

I previously mentioned Edita’s aversion to the internet. About a year after my book was released, I received a letter from Katalin Szabo, who is based in Hungary. She had just started a fan-web page for Edita, who was wary at first of having information without her consent floating out there in cyberspace. Eventually, though, the site proved to be an invaluable resource for the public, as it provided schedules of Edita’s appearances, new recording releases, and authorized online content. Gruberova.com contains the most thorough archive of her legacy.

But that was the extent of Edita’s internet involvement, and until the very end, she avoided social media and chat rooms, and would not have been the type anyway to go sleuthing around to see what was said about her. She had reached a point where criticism had ceased to rattle her; in reply to a question of those who objected to the way she sang, she just shrugged and said, “If they don’t like me they don’t have to listen.”

There was absolutely no defensiveness in this statement; the genuine menefreghista she developed as she got older was real, and a natural occurrence of her desire to eliminate the distraction of useless emotional clutter.

I was very thankful, actually, of Edita’s lack of interest in online business after the negativity I saw directed toward her, especially later in the career. She would have encountered cultural racism (her being Slovak engendered many deeply-rooted European class prejudices), misogyny and ageism. Worst perhaps was the gleeful Schadenfreude noting her voice wasn’t as under her command as it used to be.

The vicious invective was sometimes very disturbing. Online cabals against her were quite numerous: one of her most serious offenses according to these largely nameless trolls was that she sang the assoluta roles of Callas. It doesn’t stop: in May of this year I came across a few YouTube entries with one title to the effect of ”The best soprano vs the worst soprano,” the former reference to Callas, the latter attributed to Edita.

I initially found all of this grossly untidy, vindictive, and miscreant behavior deeply unsettling. As is obvious by now, my affection for Edita, both as an artist and someone I cherished personally, is pretty clear. I sometimes fired back at these insults, and I got the brunt of the cynicism and sneers too.

My reasoning was, wouldn’t you defend someone you cared about against such ugly, debasing words? Was there supposed to be a code of conduct for biographers? “Stay above it all and don’t answer to your critics?” I honestly don’t know. To this day I know no other opera singer biographers in which to compare etiquette notes. Ben Franklin’s take on that, “It is ill manners to silence a fool, and cruelty to let him go on” probably best sums up that conundrum.

I probably went too far with the protective chivalry and gallantry, but given how I feel at this juncture, I have no regrets. I did not disclose any of this nefarious chatter to Edita, and I fervently hoped none of it made its way to her. To some it extent it probably did reach her in other ways, but she never mentioned it to me; looking back, I think all that intrigue and gossip simply didn’t interest her, and it was just beneath her to give it any credence.

I don’t doubt for a moment she encountered overt hostility from some factions, but…I wouldn’t have dreamed of undermining her resiliency, for evidently she proved to be a tougher gal, undoubtedly learned from experience among the wolves, than I perhaps fathomed at the outset. You don’t get to be one of the biggest stars in the operatic firmament by being meek and timid.

Taking my cue from Edita, I gradually toughened up as well. Despite all that went down, nothing unsavory whatsoever kept her from having continued, increasing success; I fretted for absolutely nothing. Too, I discovered that the hostilities and jealousies I encountered were part and parcel of the vicissitudes of human nature. An immutable fact, not everyone is going to be happy about your success.

With all the contacts I made worldwide, I learned more about Edita beyond my own observations. Not surprisingly (to me), she was a highly esteemed colleague. Having had no previous experience with artists of her standing, I naively thought that congeniality among singers making beautiful music together surely was the rule.

Not among the higher voices, it seems. Dramatic soprano Astrid Varnay in her book 55 Years in 5 Acts made this observation: “When I hear the often-bizarre tales of great operatic rivalries, most of them involving coloraturas and tenors, I cannot help wondering why so few of them are ever told about our voice category.”

But… as good behavior goes noticed, so does the bad that spreads like wildfire. Singers talk, agents talk, conductors talk, choristers talk, opera house staff talk, fans talk.

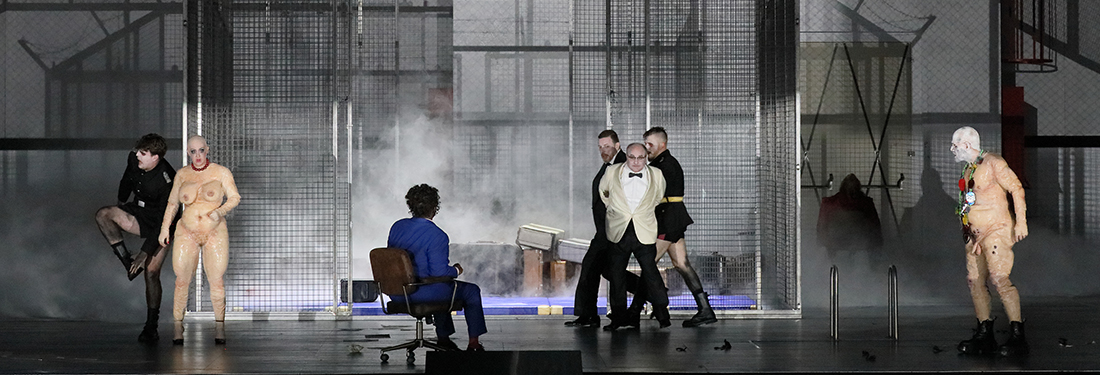

Edita eclipsed every other coloratura soprano in her generation not only because of her exceptional technique and star power, but because she was agreeable, professional, sane, and most importantly, a team player. She didn’t pull prima donna tantrums, and never gave anyone any crap. When she did pull rank, it was usually for a worthy reason having to do with workplace issues or grossly unprofessional conduct.

Edita was a star, a Margo Channing in an operatic aviary teeming with jealous Eve Harringtons. I kid you not: some of the shenanigans I heard of her non-rivals trying to pull is not to be believed. A few of them attempted or threatened sabotage of her performances, as well as spreading outrageous lies, some of them amounting to libel.

After her run of Zerbinettas at the MET, for example, she had no offers for years. Finally, Leonie Rysanek told her that rumors had been going around that Edita was tearing up all her MET offers and contracts. With Columbia Artists at the time, she found out what was going on, and the truth surfaced: an agent there representing another coloratura had been behind all of it.

Edita dropped Columbia Artists, and went with Germinal Hilbert in Munich. Lesser talents kept trying to sabotage, disparage, and badmouth her, to no avail. Instead, Edita became one of the most publicly praised artists and colleagues, and tales of her kindnesses to budding talents became legion.

Among fans, musicologists, and critics, both offering savage and, conversely, constructive criticism, there was much to learn.

Following on the heels of her formidable predecessors in the bel canto genre, Edita had from day one been unfavorably pitted against Callas, Gencer, Sutherland, Caballé, and Sills, with much conjecturing, for one reason or another, that she was lacking, in comparison to those legendary ladies.

I could understand why many would think I had a natural, prejudicial preference to Edita over the others. Well, what’s the matter with that fact? That I chose to write about my favorite muse rather than someone else?

To these criticisms and charges, I made it my business to hear for myself, and studied even harder, more intensively, seeing just what the point-by-point differences were with Edita, and her so-called rivals.

Starting with tomorrow’s post, I will give specific reasons why Gruberova remains, in comparison to the other sopranos with whom she shares roles and repertoire, my top preference!

Comments