The man has been equal parts revered by his fans and reviled by the impresarios who employed him. Some of the most gorgeous singing you’ve ever heard in your life would be followed by behavior so reckless and foolhardy it’s only a testament to the beauty of his voice, to say nothing of his formidable charm, that he regularly got away with it.

He was blessed with a golden Mediterranean sound and the juiciest [u] vowel you ever heard; “Tuuuu Puuuuria Principessa” The clarity of his diction was so sovereign you could practically take dictation. His way with a double consonant was literally envied. Plus he was movie-star handsome in his youth and an electrifying performer when he wanted to be.

He also smoked and drank to excess while gambling into the wee hours on the regular.

In Vienna, where singers were paid at intermission, it wasn’t uncommon for him to collect his fee and then suddenly lose his voice, leaving the rest of the performance to his cover while he hit the tables. The theater amended their payment policy thereafter.

From 1953 to 1956 he secured his legacy on the EMI label with a series of recordings with Maria Callas that are considered classics. In 1955 he was cast, against his wishes apparently, as Alfredo in the historic La Scala Traviata with Callas led by Carlo Maria Giulini. He detested the aristocratic director Luchino Visconti on sight. Having no patience with the rehearsal process (and not afraid to show it) he was disinvited from the revival a year later.

During a performance of La forza del destino in Naples in 1956 Renata Tebaldi sang an encore of “Pace, pace mio Dio.” Di Stefano was so put out he simply left the theater and went home.

In 1958 he pulled a disappearing act for the opening night production of Turandot at La Scala with Birgit Nilsson. She writes in her autobiography that she was furious with him when he ultimately showed up only for the dress rehearsal (!). Then he opened his mouth to sing and she said all was forgiven.

The same year Decca started recording Boito’s Mefistofele in Rome with Cesare Siepi and Tebaldi conducted by Tullio Serafin. Reports vary depending on whose book you’re reading. Either Di Stefano was having vocal troubles or simply bored with the process. He was later quoted saying, “I went out for a coffee and didn’t come back.” Mario del Monaco was called in to finish the job.

Herbert von Karajan insisted on Di Stefano for the 1963 Franco Zeffirelli Scala Boheme but he turned up so late for rehearsals (again) that the part ended up going to Gianni Raimondi. Di Stefano was paid for all the performances, however, because he was still too important to management to anger.

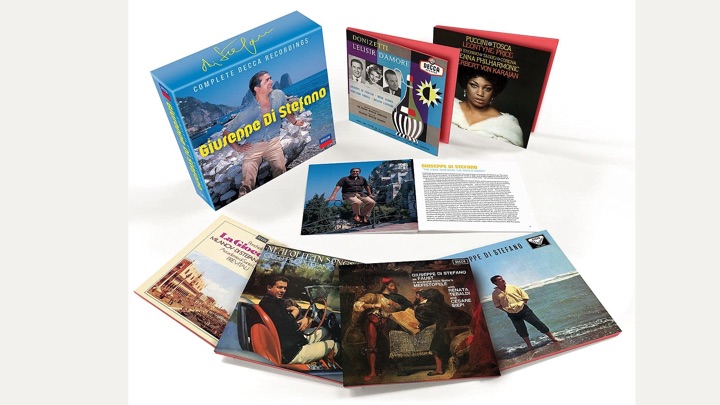

Included in this set is a fascinating documentary CD that’s produced and narrated by Jon Tolansky. We have interviews with Sir Edward Downes (who conducted one of Di Stefano’s few Covent Garden performances), Luciano Pavarotti (who replaced Di Stefano at one of his canceled Covent Garden performances), Dramaturg Roger Pines, but mostly with Di Stefano himself. Much is made of his magnetic charisma and his southern Italian rebelliousness. I believe the adjective “undisciplined” was used at one point.

The recordings included span from 1955 to 1962, are all stereo, and have been remastered and polished to a high shine.

An operatic recital disc, recorded in 1958, finds him in excellent voice and Franco Patane conducts two orchestras. For the Italian arias he leads the Orchestra dell’Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia and then the Tonhalle-Orchester Zurich for the French selections. I don’t think you could call Di Steafno’s French idiomatic but he has the perfect weight of voice for the Manon and Faust selections. In the first half he offers a thrilling “Improviso” from Andrea Chenier where he just slathers that golden tone all over the place.

Two discs of Italian and Neapolitan songs, recorded respectively in Rome 1958 and London 1964, boast the ubiquitous Cinemascope orchestral arrangements of the period but show our tenor to the manner born. So perfectly in his element he probably could have made the career solely from this genre. The catalog being so vast that he actually recorded two more albums of Neapolitan songs for EMI in 1961 and only repeated “Torna a Surriento” out of all the selections.

However, the real gold in this collection comes with the complete operas, some of which haven’t been issued on cd since the dawn of the digital age and never sounded this good to begin with.

Donizetti’s L’elisir d’amore recorded in stereo in 1955 (but initially released as mono) finds our tenor well partnered by Hilde Gueden, who’s pert and charming, and a hilarious Fernando Corena as Dulcamara. The chemistry between the three of them is palpable. The music making, with numerous cuts, is of its era. Di Stefano owned Nemorino for a time and it shows. In a role that doesn’t tax his resources in the slightest he’s simply having fun and flaunting that sunny Sicilian timbre.

The next two operas are Ponchielli’s La Gioconda recorded in “57 and Verdi’s La forza del destino in “58. Both with the same quartet of Zinka Milanov, Leonard Warren, Rosalind Elias and Di Stefano. These come from the time when Decca and RCA enjoyed a mutual agreement regarding artists and distribution.

Milanov’s career was so centered at the Metropolitan in New York I’m sure it was considered a duty at the time to finally capture her in these signature roles. She’d been singing for well over 20 years at this point and although she exhibits all the familiar mannerisms of her late career there is a lot of spectacular vocalism.

The breadth of phrasing and the command of legato are there most especially in Act One and Two of Forza. The duet with Di Stefano before the elopement (that doesn’t happen) is white hot and she’s magic in front of the monastery in the duet with Giorgio Tozzi’s Padre Guardiano (who’s no slouch himself).

Also it was common practice at the Met to cut the whole of Act Two, Scene I of Forza back in the day. You’d get Act I, then they’d play the overture (while they shifted the sets backstage), skip the scene at the Inn all together, and go straight to Leonora on the lamb and her big scena with the monks (I think John Dexter finally restored it in the ’70’s).

Plus MIlanov had that float. In the Gioconda her “Enzo adorato! Ah, come t’amo” has that magical piano B-flat that she was so famous for. It’s like it stops time. Frankly it’s better in the studio than either of the earlier live performances that the Met on Demand app has. I don’t think her “Suicidio” has been equaled either.

Elias, another Met stalwart, is surprisingly strong as Preziozilla and touching as Laura. She’s on top of her game musically for the Forza with all the tricky rhythms and tongue twisters. In Act Two of Gioconda she and Di Stefano are swoon worthy in their duet. Then squaring off against Milanov she’s gutsier than you’d imagine.

Leonard Warren sounds wooly to my ear but I get that it was a really rich dramatic baritone. It’s also obvious he’s had plenty of experience, like Milanov, in both his roles and it makes for a far more flavorful and theatrical experience.

Di Stefano’s contribution is a little harder to qualify. He’s singing above his weight class in both these operas and I’ve heard stories over the years that there were late night tracking sessions because he wasn’t interested in showing up during the day. I don’t know how much of that is true. It’s easy to identify his enormous need to communicate the text to his audience and he’s especially nuanced in the Forza. Still it’s a great pleasure to hear him in both these roles and he really shines as Enzo Grimaldo.

Fernando Previtali helms both ably along with the Coro & Orchestra dell’Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia. These are two operas that were so commonly performed at the time that have now essentially become rarities.

The excerpts for that Mefistofele that ran aground are included (and I’m certain I’ve heard them somewhere before) and Cesare Siepi is great but I think it might be one of Tebaldi’s best recorded performances. Her “L’altra notte” is hair raising and not as ungainly in the vocalise portions as we usually hear. We’ve got the Santa Cecilia bunch again with poppa Tulio Serafin driving, proving once again it’s about experience.

Then Decca essentially put Di Stefano in the dog house until 1962 when von Karajan requested him for his new recording of Tosca.

Having performed the role in English in an abridged NBC broadcast in 1955, Price had just sung her first staged Tosca at the Met that spring (and her second performance in that run is available on the Met on Demand app). She’s 35 years old here and the brazen glory of her voice, and in particular her upper register, is electrifying.

I find her a nearly perfect Floria Tosca. Sensual and teasing in the Act One duet with Cavaradossi and then ablaze with betrayal in the interview with Scarpia. Absolutely kaleidoscopic with the many parlando line readings and effects.

Giuseppe Taddei, another Karajan favorite, is the Scarpia. The Italians had a saying, “We gave Gobbi to the world but we kept Taddei for ourselves,” and you can see why. The word pointing is extraordinary. The problem is he’s completely malevolent throughout, a wolf in wolf’s clothing. Still he’s completely aristocratic which is what the part demands.

Karajan and the Vienna Philharmonic make certain that this is absolutely the most beautiful rendition of Tosca ever committed to disc. Helped along of course by the Cinerama soundscapes of producer John Culshaw and his faithful knob-twisters. The church bells, the cannon fire, the off-stage cantata choir, the doors and windows slamming, the morning bells of Rome: It’s all there in detail so crisp it sounds like it could have been recorded yesterday.

Plus Karajan’s conducting isn’t as mannered as it would eventually become, although he certainly draws plenty of attention to himself. No question he’s exhilarated by the current company and the freshness of Price’s portrayal.

Here, I’m sorry to say, Di Stefano is the weak link. While he has many moments of strength, especially in the Act Two interrogation, he’s simply not in good vocal estate. When he’s singing softly you get the magic but when he has to move up the staff it becomes explosive.

I think this recording is currently on its third remastering (2000 when it was kicked up to 96kHz 24-bit and then again in 2017 for Blu-ray audio) since it was transferred to CD via ADRM way back when. Initially the brightness of digital sound didn’t do our tenor any favors but with each succeeding transfer they’ve managed to buff him down a little so his faults aren’t as glaring (literally). All in all this is by far my favorite recorded Tosca. It’s so wildly opulent on every front that it sits in a class all by itself.

I fell in love with this man’s voice listening to these performances. He’s the anti-Bergonzi. None of that classical reserve or the measured tone. He’s completely in the moment so none of that reliability either. Yet there’s an urgency, a real vibrancy, that comes across as uniquely his.

In some of the big lead-ups, if you have the ear for it, you can hear the splices where another take was used for the sake of the high note that’s coming. But that’s more about the pressure of the studio I think. I already had so many Di Stefano recordings, just because of his association with Callas, but now I wouldn’t part with these, warts and all, for anything.

Comments