Even though this played in my favor for the very reason of Edita’s being confident that I was worthy of writing about her singing and art, I was basically an uninformed young man about life and the ways of the world. It was not until years, long years later, that I understood the basis of that patience and kindness. Mature adults with much life experience, especially women, are able to intuit in young people a kind of sincere, unformed earnestness about them.

Most keen, knowing, compassionate adults regard and deal with young people with empathetic understanding. This is what I retrospectively understand of Edita, in her dealings with me. The odd conundrum in writing this, more than 30 years after I met her, is “channeling” my younger self to the way I was and reacted then, to now, being informed and enlightened by life.

I hasten to add, though, that she in no way “took me under her wing” or assumed a “life-tutor,” mentor role (the prospect is an appallingly ludicrous cliché if ever there was one). We were not confidantes, and did not exchange details of our separate, private, personal lives at any juncture. It did not so much as enter my mind to even think of asking boundary-crossing questions; even curious musing felt disrespectful. Looking back, it was an impeccably tacit collaboration, remarkably unimpeded by conflict or mistrust.

She was good to me not because it held an advantage to her, but because it was an inherent part of her fundamental constitution: Edita was one of the most decent people I have ever known. Most crucially, no matter how weary wary she may have gotten from the turmoils and tribulations of her professional life, that basic persona of the nice, polite young woman from

Ra?a never left her. Artistic temperament she had, but not including self-centered megalomania. She was one of the most fully human individuals I have ever known.

Rather, it was the very simple circumstance of mere association with Edita that advanced my own worldview and knowledge about people, and life. For nearly half a dozen years, I listened to a woman who’d been put through some dreadful paces in her life, traveled the world, worked with every kind of person in her profession; I therefore absorbed—and learned. From, perhaps, an ideal source. As Edita told, I became better equipped to do the telling.

Too, I received the ultimate 101 course on how to handle fame and success. I witnessed Edita receiving rock-star adulation, mad-frenzy ovations, and mob scenes after her performances (YouTube videos of her visits to Japan and China have to be seen to be believed).

None of this turned her head, and she remained almost defiantly unimpressed with herself until the very end. Never talked about her successes, never “sales-talked” her recordings; once she approved her takes in the post-production listen-throughs, she was done. I found out of an important element of her sense of ethics: on some of her recordings a high note would go awry or flat, yet she resolutely refused “post-production fixes”—“That is not only dishonest, but it would leave the false impression that all performances are perfect!”

Ethical, too, was Edita’s respect for the great majority of her colleagues. There was a baritone with whom she’d worked who needed extra consideration owing to his nervous state.

As she tried to explain his dilemmas, she cut herself off and said, “No. I don’t like to speak about my colleagues like this. We have to be together in the same direction, to make the performances good. We are worried about our voices, we are afraid of getting sick, about hundreds of details we have to remember, and there are problems, always problems. You can’t believe the life of a singer.” She pointed first to her throat, then her head, saying, “Here and here we are at the mercy of them. Our nerves and our throat.”

One day in 2002, I was conducting a phone interview with Edita for a possible article, specifically regarding vocal technique. She was holding forth that the test of the durability of the technique was revealed when singers reached their 40s.

I ventured the example of Natalie Dessay, who at that time was having vocal problems. Edita interrupted and said, rather testily, “Wait, what what what? Who told you, how do you know this???” I told her it had been reported and discussed on opera sites.

She made a noise of exasperation, and went on, heatedly, “The internet?? This is a very personal, very nervous problem for Natalie, and they are talking about her on the internet??? I don’t like this, that everyone should know about her private problems. People do not understand what this means for a singer! Natalie is a very simpatico person, a great artist, and she is afraid for her career, do you hear me?”

Edita held the internet with deep suspicion and paranoia; having once lived in fear from the communist state’s tracking of information protocols, the internet initially unnerved her sensibilities.

The one and only time I heard Edita speak ill of a colleague concerned a tenor with whom she frequently sang. This tenor was brought in at the last minute in a new production of Lucia di Lammermoor, when the originally slated one had to cancel out of illness. After the run of performances ended, it became known that this tenor agreed to substitute on one condition: that he receive a substantially higher fee than Edita.

Of course, this blackmail bargaining tactic to undermine her behind her back did not sit well with her, and, stung by his treachery, Edita never sang with the tenor again. When she finished telling me this, her characteristic giggle emerged, and said, “So now I become a feminist!”

At last, the book went into its advanced stages. The main of my manuscript translated into German, it allowed Edita to proofread, fact-check, and to insert her own direct statements and comments in the appropriate places, which made it exactly the collaborative effort I desired. The logistics of the English-to German undertaking posed its myriad challenges, but they were all surmounted by the people in publishing who deal handily in these matters.

My last stop during the book project years was Vienna, May 1994, for the Staatsoper’s first-ever production of I puritani. This was a genuine holiday, with no work-related matters pending.

This, too, was my first time seeing Edita in her alma mater of Vienna, the place where she was groomed and made into a star. It was for me a “holy grail” destination.

The new production was a rather avant-garde affair that changed the ending of the story into a tragedy (Riccardo returns back onstage, and in true baritone-with-a-vendetta fashion, stabs and kills Elvira’s beloved Arturo); it featured an all-star cast including Marcello Giordani, Dmitri Hvorostovsky and Roberto Scandiuzzi. Placido Domingo conducted, though he was ill-at-ease in handling Bellini.

The most notable event other than the two performances I saw (in addition to the obligatory sight-seeing), was having the opportunity to meet Edita’s famed singing teacher, Ruthilde Boesch.

I went with Edita one day to the opera house, where she took me around on a tour. She was met with one of the vocal coaches, who asked if she would come with him to hear an audition. We were led to one of the large practice rooms, where a young American baritone was waiting.

The baritone’s eyes widened when Edita walked in. He proceeded to sing “Di provenza” from La traviata. The voice was quite sizable and of indubitably fine quality, but he struggled in the upper register, the tone sounding uneasy, strained and plugged-up.

Edita told him, “You have a wonderful voice. But you are not using it correctly! What is happening up high, this quality of tone you are making?” The baritone didn’t know what to say. “Who is your teacher, how long studying, where do you sing?” The baritone gave a name, and told Edita he’d been with his teacher for ten years, and had only been in one opera nine years previously, in a comprimario role.

A look of incredulous disbelief came into Edita’s face. “You have been with this teacher for ten years and she has made your voice like this?? No, no, no, this is not right. Three, maybe five years with a teacher, no more, and a singer should be ready for performances, on the stage. I see this situation all the time, it is very bad. These teachers ruin voices and make promises they cannot fulfill.”

She thought for a moment, and told the baritone, “I would like you to go see Mrs. Boesch, my teacher. This is ok, no?” The baritone, taken aback, expressed interest and offered rather abashed thanks, unprepared for this sudden turn. Edita excused herself to make the phone call, and returned shortly: “Mrs. Boesch will see you tomorrow at 2:00.” She then asked if I would go to the voice lesson with the baritone: “I cannot go, I have a performance tomorrow night, and I must rest. But you can meet Mrs. Boesch!”

The next day, I went with the baritone by tram out to a charming suburb quite outside of the Vienna city limits. The petite Mrs. Boesch welcomed us inside and offered us tea. She was as Edita described: energetic, extroverted, and upbeat.

Once the lesson began, though, she was all business. She had the baritone run through some sets of scales, and I saw her frown as he once again revealed his strained upper register. Mrs. Boesch got up from her chair and stood right in front of her last-minute student. She instructed him to repeat the last set of high-lying scales. Sweating profusely and turning red, he proceeded, while Mrs. Boesch looked intently into his mouth.

“Ah ha!” she exclaimed. “Your tongue goes back and up when you sing into your upper range, blocking the projection of the tone and creating tension in your neck and jaw. Your teacher did not correct this?” The baritone, as with Edita, couldn’t come up with any reasonable response. An hour later, after intensive work and prompting, Mrs. Boesch had succeeding in getting him to relax his tongue and jaw, with remarkable results; the voice sounded freed and open.

At the end of the lesson, Mrs. Boesch told the baritone, “You now know what to do. What you do about it is up to you. But you will need to work hard to correct your very bad habits.” Looking to me she said, “I am sorry but I don’t have any time to talk about Edita, as I have another student shortly. But I can tell you that the reason she has a big career is because she worked harder and practiced more than any student I have ever had. This is why, there is no special secret.”

After returning to the city, the baritone and I parted company. I never heard from or about him ever again; on the ride back, he had not said much, and did not seem particularly happy. At one point he said, almost more to himself: “What am I going to tell my teacher back home? I can’t stop studying with her.”

Later that night, after the last performance of I puritani, I joined Edita and Friedrich, who had arrived to retrieve her, for a late supper at a cozy, tavern-like restaurant nearby.

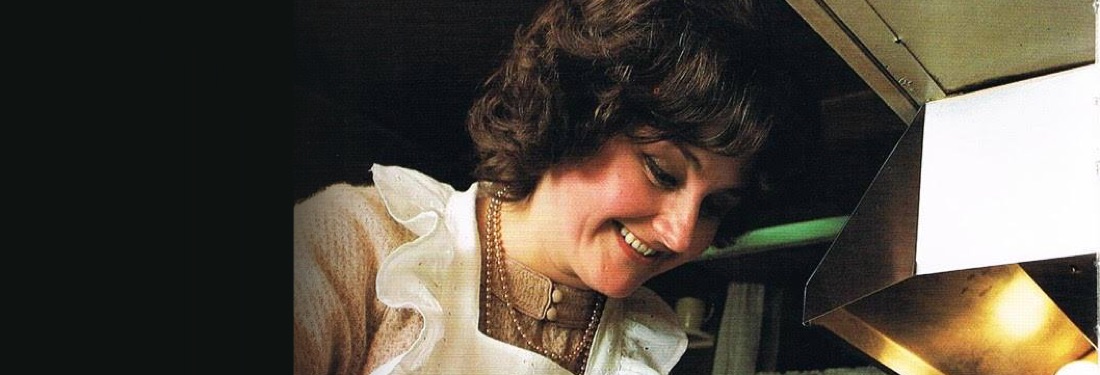

I picked up the menu to look through it, but Edita said, “No, no, no, I will choose for you. You are in Vienna and you must have Wiener Schnitzel!” She was quite right—it was something delicious. The conversation was light and casual, and we celebrated and toasted the conclusion of our endeavor of nearly six years.

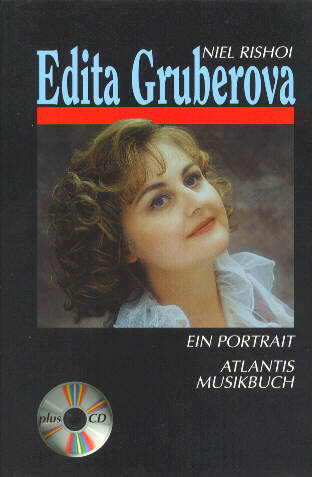

Flash-forward to March of 1996. I received word from the publisher that my book was finished being printed and was going to be released shortly.

On March 20, DHL courier service knocked on my door. There it was, beautifully mounted and presented. Atlantis Musikbuch gave the book a luxury packaging, complete with photo inserts and a sampler CD.

However, I was not done learning about Edita Gruberova; the years and decades following provided greater insights and revelations into her art.

In 2000, after I had been hooked up to the internet, I joined a few online opera discussion groups.

In the four years between the publication of my book until then, I had had very minimal contact with other aficionados of opera.

In these groups, I encountered quite an illustrious number of seasoned, long-time opera-goers, other critics, singers, and musicians, from all over the world. I made a few friends, who remain so to this day, who were also fans of Edita.

But it was her severest critics and detractors I most learned from!

Comments