Barcelona was my favorite of all the European cities I visited. It has a raw, earthy sensuality and vitality which I took to immediately. With me were my friend Shirley and her brother Tom. When we got settled in our place of lodging, Hostal Levante, which was right off La Rambla near the opera house, I called Edita to let her know we had arrived.

All was definitely not well with her: she’d just gotten back from the final dress rehearsal when she discovered that some thieves had broken into her hotel room and stolen all her jewelry, including a few treasured pieces that had belonged to her mother.

She was both heartbroken and livid: the doors leading out to the balcony had no durable locks on them, and her room was entered with little effort. Edita’s voice grew savage as a whiplash as she described the apathetic, bumbling indifference of the police, and she was positively fuming in a way that would scare the Queen of the Night at the hotel management’s lackadaisical security.

Most alarming of all, she declared that she was going to cancel the entire run of the opera and go home, “I cannot sing Anna Bolena after this!” She vented for a few more minutes, and I sympathized with her sorrow and anger. Finally, with a deep sigh, she said, “I probably will not cancel, but I need to go to sleep and get some rest. I am so sorry you hear me like this.” I reassured her all was ok, and that I understood. I took it as a sign of her trust in me that she felt uninhibited to vent so freely.

The premiere was a rousing success for Edita, with storms of applause and long ovations, but of the three performances I saw, something positively electric and seeming of a supernatural element occurred in the second performance. Most opera singers will testify that out of hundreds of performances, they will feel that they were at their absolute, near 100% best for maybe five to seven of them, where they felt everything, all the crucial elements, fell right into place.

On that second night, Edita was in stupendous form, and in the “Al dolce guidami,” in the phrase “del nostro amor,” in the section where the slow, florid line ascends upward, and in an ever-broadening ritard, she drew the phrase out longer, and ever longer, in one, endless breath; this floated out in the expanse of the opera house like a warm, shining star hovering about. I heard a sniffle and turned to see Tom weeping.

After Edita similarly drew out the final phrases of the aria with the finest gossamer tone, the audience nearly blew the roof of the house off as they crashed into thunderous, hollering applause, which went on for a full 5 minutes. The curtain calls at the end lasted for well over half an hour, the audience roaring their approval as Edita appeared, over and over again; they did not want to let her go.

The night of the premiere, though, was the most memorable because of an incredible act of generosity that further affirmed of Edita’s intuitive, giving nature.

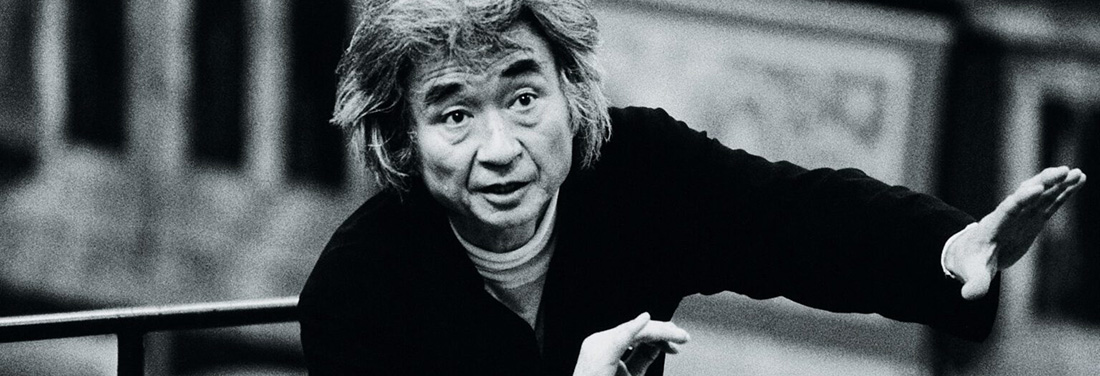

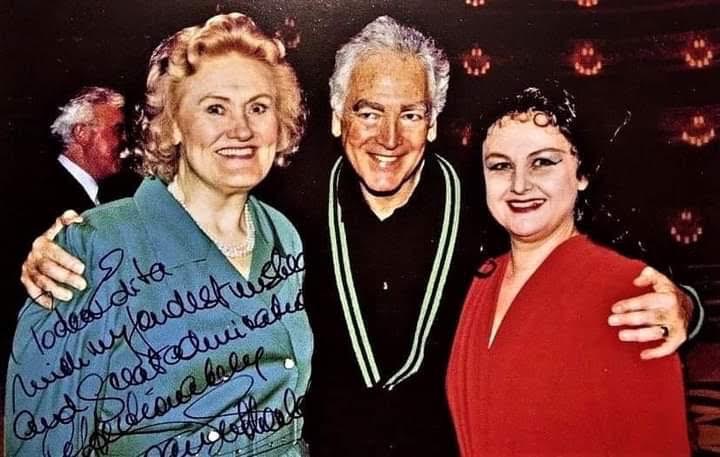

After the performance, when the auditorium finally cleared, I joined Edita on the stage, who was in animated conversation with Friedrich Haider, the opera’s conductor Richard Bonynge, and with him was Joan Sutherland. The legendary Australian diva took Edita’s hand in both of hers, warmly praising her. The affection between the two ladies was palpable.

As opera in Barcelona started at 9:00, it was well past 1:00 a.m. when Edita had shed her costume, got dressed, received fans, and signed autographs. Shirley and Tom waited with me to congratulate Edita and to wish her and Friedrich good night. Tom, obviously moved, told Edita how much he enjoyed her singing, and he was overcome and somewhat abashed as he tried to find the right words. I saw something register in Edita, of being deeply touched, and she took Tom’s hand and said to all three of us, “Please join me and Friedrich and my colleagues for dinner, you are my guests!”

When we got to the restaurant, Edita motioned for Tom and Shirley to sit next to her. There were at least 15 of us there, an assorted group consisting of a few of the cast, agents, and associates. The afterglow of the successful premiere infused the meal with animated conversation, and much good cheer and laughter. Edita was in wonderful spirits, and I saw her wit in full display.

But she was particularly attentive to Tom and Shirley, making sure they felt welcome and included in the conversation. Various languages flew back and forth, and Edita turned to my friends quite often to make sure they understood what was being discussed. All I could do was look at Edita in amazement at her kind generosity of spirit. It was 3:00 AM. before we got back to our Hostal, and Tom told me, “This is the happiest night of my life.”

The next day, Tom suffered a mild heart attack and had to be hospitalized for the rest of the stay. Edita, hearing of this, was genuinely concerned and sent him flowers and a note of wishes for his recovery. Until Tom died 10 years later, all he could ever talk about was how kind Edita was to him. His sister and niece both told me they’d never seen such a change in him, of a new kind of softness and gentility. Tom was a driven, intense man who had to go to work when he was 13 to support his family after his father died; never married, the majority of his life in a very demanding job was spent in service to others.

In the meantime, Edita invited with me to sit in with her, over a few days, at the annual Francesc Viñas vocal competition, where we could catch up and sneak in some more discussion time. It was fascinating to watch her various reactions to some of the contestants. Many of the singers had vocal problems, and she always attributed this to mediocre teachers—“What are they teaching to these young singers???”

One of the judges was Magda Olivero, and after I expressed my admiration, one of the agents I’d met urged me to go over and meet her. I tried in my limited Italian to tell her how I wished I’d had a chance to see her perform in person. She was graciousness personified, and had the bearing of a refined, great lady.

On another day where I was situated, Joan Sutherland and agent Menno Feenstra—who were also adjudicating—came in and sat right behind me. Sutherland bade me a cheery hello. At one point, a soprano doing the mad scene (alas, poorly) from I puritani had obviously learned it from a well-known American soprano’s recording—the phrasing and ornaments were identical.

After the contestant finished, I heard Sutherland murmuring dismay to Feenstra at the contestant’s mediocre technique. I turned around and told them what I knew.

Sutherland fairly exploded, “But of course she learned it from a recording! That’s all they do nowadays is listen and borrow!” After the day’s competition ended, all the luminaries walked out together, in lively chatter. I stood off to the outside of the venue and waited for Edita. Olivero saw me and winked and waved, to which I reciprocated. I heard Sutherland’s parting comment, accentuated with concern, to Edita, “Get some sleep!”

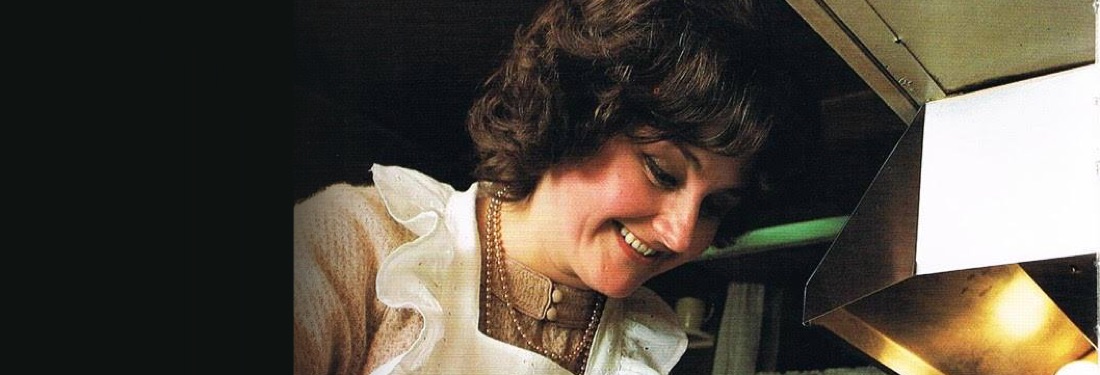

I found out what was behind that maternal comment. The next day, I joined Edita and an executive from her record company, Nightingale Classics, for lunch. She was tired and on edge, announcing she was not going to talk much before her performance—“I am so sorry, I am nervous, always nervous before I have to sing a new role. I don’t sleep so good.”

The executive explained to me that Edita’s nerves were not worry about her technique and voice, but of the responsibility she had by nature to give the audience her very best, of needing to summon superhuman reserves of energy, most especially for new roles (and she considered Anna Bolena the “Brünnhilde” of her roles). The worry disrupted her sleep, which compromised the requisite energy she needed to have. After hearing all this, Edita looked at me and nodded, rather wistfully.

On another day, after a seafood lunch on La Rambla near the waterfront, Edita needed to go with Friedrich and meet some of their associates at the opera house. I was introduced to an imposing, but warm, lively woman named Gloria, who was an artist’s agent for the Liceu. As

Edita and Friedrich had some business to discuss, Gloria took me on a private tour of the Liceu’s many stunning rooms and halls, and told me much about its history. She asked how I knew Edita, and I told her. Gloria then said, “ I have to tell you that Edita, along with Mirella Freni and Joan Sutherland, are the most polite and kind singers I have ever known. Edita is always saying ‘please,’ and ‘thank you,’ and she has the most gracious manners. You are very lucky to be working with her because believe me, prima donnas like her are rare to find.”

Near the end of our stay in Barcelona, Edita invited me and Shirley to go with her on a brisk, sunny day to an outdoor song recital in a walled-off square, given by Elena Obraztsova. In a recital of mainly Tchaikovsky songs, the mezzo was slightly past her best, but that huge voice resounded mightily out in the open air, and she was met with lusty, adoring approval.

The day before we left Barcelona, Tom was released from the hospital, and though he was too tired to attend the third performance of Anna Bolena, he was in good spirits. Edita asked me and Shirley to let her know how he was doing, and heartily thanked us for coming to see her, with our own return effusive thanks for her above-board hospitality.

That trip home was silent: all three of us were treated like royally by a kind star prima donna, and we were overcome by a kind of awed wonder and contentment.

Comments