Bellini’s Norma is basically a one-woman show. None of the solos of Pollione, Adalgisa, and Oroveso in contrast have any music comparable in imagination or memorability, except when they are in Norma’s company–how many tenor, mezzo, and bass recorded recitals excerpt numbers from the opera?

Arguably, Norma is the most criminally miscast role in the entire soprano repertoire. It’s a role requiring stylistic élan, a sound, florid technique in slow and fast passages, and the performer’s being conversant in the musical language of Romantic bel canto opera. And not least, sheer beauty of tone is a must–the construction of the elegiac, melodic disposition demands it. Norma’s wide range of (mostly conflicting) emotions are all pretty basic, their text readily easy to convey thanks to librettist Felice Romani; even if the soprano has faltered technically, the music never fails to pluck at the heartstrings The lyrical last scene, especially its concluding great E minor/major/minor modulation, practically sings itself.

It’s a superstar role that attracts every kind of soprano; and that is exactly the problem. Quite often if one looks at the repertoire itineraries of many sopranos, there will be only one bel canto entry listed: Bellini’s Norma. The deficiency in knowing how to handle this role is borne out in the careless, unscholarly way it is frequently delivered.

And that is why many singers often proceed as if the opera were composed by Mascagni with Norma sung like a Black Belt Santuzza–with Azucena’s hairy chest low notes. Today, we still have exponents of the role who feature blowzy, blustering, and unlovely tonal emission, clunky, approximated scalework and divisions with parlous, wayward upper registers. The role vaults much more frequently into the upper regions than low. Such approaches look anachronistically into the inappropriate and incorrect method of singing bel canto in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Veristic and Verdian applications to the role are all wrong. Bellini’s score actually harkens back to the Classical period. The scoring and orchestration is Northernish, often lunar in tonal color, exposing the lithe vocal lines; there’s not a moment calling for the size or vocal thrust of a Turandot, but a Turandot, to our everlasting frustration, is what we often get. As a result, casting expectations are often based on the frequency by which the wrong voices mangle the role, instead of the source score.

And what of using Giuditta Pasta, the original Norma, as the basis for casting the role? We know she had vocal problems, including severe pitch issues (it was reported that the violins had to tune down to her extreme flatting). We know that she told Bellini that “Casta diva” wasn’t right for her initially (and the key of F became known as the Pasta Key, even though Bellini wrote it first in G). We know that Pasta created Amina, too, a completely different sort of role usually cast with light sopranos. Few of today’s Normas sing Amina. I would hazard that Pasta’s voice was probably like Renata Scotto’s, rather than Renata Tebaldi’s, with probably a “straighter” tone, less vibrato than is used today.

It’s a demanding, but not impossibly difficult, role, provided the soprano has the technique for it. But we often get the worst techniques imaginable. Save for Rosa Ponselle and Rosa Raisa’s recorded excerpts, many early 20th century sopranos took an all-purpose, often veristic assault on the role. Much of that earlier era’s approach, however, was corrected in the 1950s by Maria Callas, who, though fraught with vocal problems, understood and indelibly conveyed Bellini’s special idiom while dealing with the cuts and transpositions of the middle 20th century. Claims that Callas incorporated veristic elements into the role just aren’t so, though her faulty vocal production caused the tone to turn strident during highly charged, declamatory moments.

It wasn’t until 1965 Decca recording with Joan Sutherland that Richard Bonynge, restoring cabaletta repeats and portions from the original autograph manuscript, brought out a performance edition that seemed to be truest to the intentions of Bellini, as much as we can conjecture them. And Sutherland, despite her lack of dramatic specificity, sings by far the most supremely technically secure account of the role ever documented until that time. If Bonynge’s or the new Prima critical edition, with their original keys, restorations, and variazioni, were strictly mandated from here on, they would not be performable by many Norma wannabes.

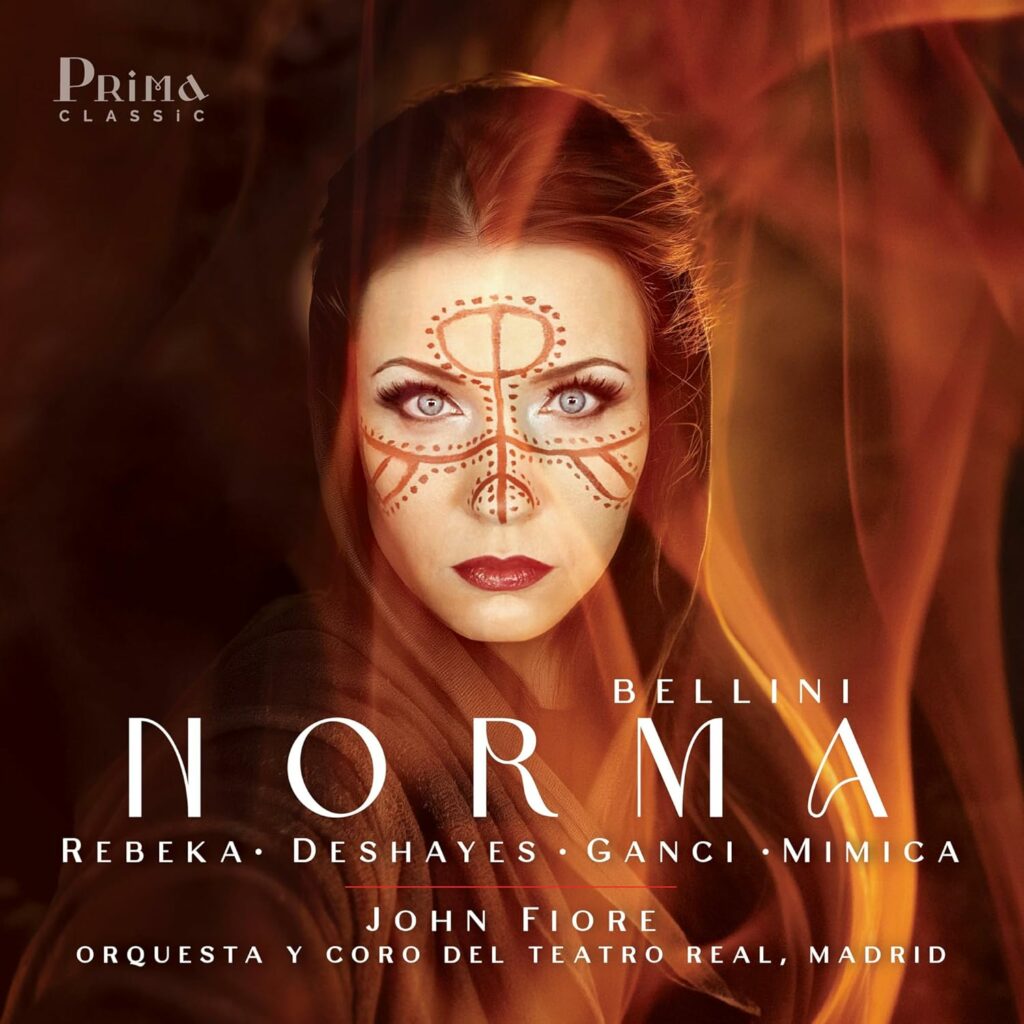

The new recording on Prima, a label owned by Rebeka and her husband (Edgardo Vertanessian, also credited as the sound engineer), bills itself as using a new critical edition spearheaded by Roger Parker who outlines in the detailed notes his restorations and changes. But Bonynge put back most of these parts in this then-new edition in 1965. The Decca complete recording featuring Cecilia Bartoli also implemented these restorations. So, we’ve heard all this music before.

Ideally the restoration of these parts should be utilized in performances from here on. Norma’s “Casta diva,” restored to the autograph key of G major, is the “‘right’ key”, according to David Kimbell, author of the Cambridge Opera Handbook: “[Approached] from the previous recitative via a characteristic Neapolitan modulation, left again by the G pivot note of the banda that launches the tempo di mezzo.” Not that there are any real objections to the traditional version in F, especially if the protagonist lacks a generous upper register which the tessitura in G requires.

The Act I terzetto “Oh! Di qual sei tu vittima” sensibly restores Adalgisa’s lines right after Norma’s. The act two Norma/Adalgisa duet “Deh con te…Mira o Norma” is in the untransposed score keys of C and F, not its usual keys of B flat and E flat. I don’t like the lower keys: they sound drowsy and doleful, rather than the higher’s more bittersweetly urgent and fervent pathos. The hushed maggiore section concluding the “Guerra!” chorus, with Norma’s slow, ascending arpeggio, is given in full here. The act two prelude, first heard on the second Bonynge/Sutherland recording dating from 1984, is here opened up: the con dolore cello melody is played twice, the striking repeat with the clarinet and flute joining the cello.

Parker omits mentioning, though, that the act one “Ah! sì fa core abbracciami” is also opened up, with quite a florid repeat that we previously heard Sutherland and Marilyn Horne expertly negotiate in the 1965 recording; Bartoli and Sumi Jo in their recording also include it.

This new venture, featuring Marina Rebeka in the title role, Karine Deshayes as Adalgisa, Luciano Ganci as Pollione, and Marko Mimica as Oroveso, headed by conductor John Fiore, was recorded at the Teatro Real, Madrid, with its orchestra and chorus in August 2022. The booklet emphasizes that it was not recorded live.

The packaging box is quite deluxe: the CDs are held in separate envelopes with handy track listings with a lavish booklet featuring photos, bios, libretto and English-only translation and a fine musicological essay by Parker. Deluxe is the price, too: a whopping $63 on Amazon. It’s also available for streaming.

Is the price worth it?

For Norma aficionados and scholars, perhaps. But it boils down to the performances of the singers. Whether this will be deemed as a part of the opera’s esteemed recorded lineage and performers remains to be seen.

I’ll just say right here that this is one of those instances where being a reviewer is a very mixed prospect indeed, and having to be critical of all the good intentions and efforts poured into this endeavor – which is of the fullest account of the score – is for me rather sad. I so wanted this to fulfill eager expectations, so wanted this to rally gloriously as an important landmark document.

Ken Howard/Metropolitan Opera

The first and main problem is the microphoning and post-production engineering of the singers. One would think that this being recorded in an opera house rather than an airless studio, the theater’s spaces might provide a semblance of how voices resonate in the house’s acoustics; but no – the mics are audibly RIGHT THERE, not inches, but seemingly centimeters, away from the mouths of the singers. The singers don’t blend in with the orchestra, they often seem to drown it out.

The male soloists come off best. Ganci, a name new to me, has a bright, firm, and attractive tenor, his crisp Italian is a real pleasure, and he portrays Pollione convincingly. His aria “Meco all’altar di Venere” and cabaletta “Me protegge” are musically and cleanly sung, with a good high C. There is ardor in the duet with Adalgisa, involvement in the dramatic confrontations with Norma, and his overall contributions are definitely affirmative.

Bass-baritone Mimica, too, is firm in tone, incisive, with excellent Italian. He does what he can with Oroveso’s rather stolid vocal profile: solemn in “Ite sul colle,” and both vigorous and graceful in “Ah! del Tebro.” The relentlessly close microphoning bears witness to how firm are the voices of Ganci and Mimica, but you readily sense that the aural aspect is not faithful a reproduction. A check on YouTube of Mimica in live videos reveals a voice much more resonant, pingy and ringing, one that booms out with impressive, expansive power. This recording undercuts all that.

Deshayes, the Adalgisa, also sang the title role of Norma in Aix-en-Provence in 2022–a month before this recording. As a mezzo-soprano, she has had success in Rossini; a 2014 performance in La cenerentola reveals an attractive, rich tone, agile, and a charming delight as an artist. Her repertory consists of standard mezzo roles.

The Aix Norma, uploaded on YouTube, is not a success. It would appear that Deshayes is trying to push her natural endowment into soprano territory, with variable results. The top is fluttery, insecure, and she whitens and thins out her tone to hit some of the higher portions of the role’s writing.

Unfortunately, her Adalgisa here is not much better, for the same reasons, not helped by the incessantly close microphone. The core of the voice seems to be receding, and just about all of her singing in the upper register is spread, and there is a persistent flutter whenever she exerts pressure on the tone. There are few places where Deshayes sounds truly at ease. Her sortita, “Sgombra è la sacra selva,” is the one place where she’s poised, eloquent, and conveys the pensive mood most effectively.

But in the numbers with Pollione and Norma, any time the line or the dramatic temperature rises, the tone becomes unfocused and unruly. If this is the result of Deshayes trying to expand her extension, I hope she will reconsider returning to her métier as an outstanding mezzo. One bit of nitpicking, which many other Adalgisas are guilty of: the line “Io l’obbliai” is marked by Bellini’s instruction con messa di voce assai lunga. Deshayes just flings it out loudly. Count on Montserrat Caballé in the 1984 recording to get it right.

Of Rebeka in the title role, I’ve been trying to get at the gist of why her voice has changed so. She is an international star of the first order, a committed, intelligent, dedicated artist, and a vivid, consummate actress. But something has gone wrong with Rebeka’s singing as of late and those problems are further and alarmingly exacerbated in the present recording.

I think I finally found my answer of why, going back in time, YouTube being once again a handy resource. Here is Rebeka singing Donna Anna’s “Non mi dir” from 2011:

This excerpt exhibits a gorgeous, shining tone, pealing, resonant, and the long-lined phrasing resplendent. It doesn’t sound anything like that now.

As Norma here, she’s doing something very untoward, and it appears destructive to her voice. The mic placement is no help, but what I hear is a deliberate, conscious pushing on the voice to be dramatic, audibly darkening it, a very cupo sound issued from the larynx; the unceasing glottal attacks grow wearisome to the ear. I was reminded more than once of Leyla Gencer. The result, then, is a hardening of the tone, loss of resonance, and a worrying pulsing creeping in.

It would appear that Rebeka is undertaking a new resolve to be something she ardently wants to be and perceives as a step of her burgeoning artistry: a dramatic mistress of bel canto heroines. I wonder if this misguided thickening of her vocal means, her self-conscious thrusting and pushing of them, is her way of paying homage to Callas? Rebeka appears to be taking an artificially weighted middle voice and hoisting it up, and it doesn’t “turn over” once above the staff. The one genuine surprise is the Sutherlandian E-flat that she issues at the end of “Gia mi pasco ne tuoi sguardi.” It’s the most successful upper-note in the entire performance, including the ones immediately preceding. There’s a high D at the end of act one, but it’s a bit driven, which may be the intent owing to the high-octane dramatic situation.

What is such cause for regret is that upon Norma’s entry, the “Sediziose voci” seizes the listener’s attention immediately; it is alert, flashing with vivid declamation. But nearly every line is punctuated by hard strokes of the glottis. Then in the “Casta diva” everything falls apart. Though it is sung in G, Rebeka adopts a hooded sound that causes a slight clucking, hooting along the line. “Diva” is aspirated: “dee-hee-hee-hee-va.” You can hear the tensing as the melody begins to climb higher. Then the repeated top Bs and C are attacked with wild shrieks. The voice thins out during the “senza vel” passages above the chorus. The second verse goes slightly better, and the final phrases are lovely, the “nel ciel” sung down, as per the score.

What’s odd is that though this is taken in G, it sounds like the tonal coloring of the version in F; so instead of the shining, released tone she had in the “Non mi dir” I posted above, the deliberate thickening here causes the line to appear dragged under, while conversely pushed:

Nearly a year before this recording, Rebeka sang Norma in Catania. The aria is sung in G, and though the mic’ing is better, much the same results transpire, and you can visibly discern the throat reacting to the clucky darkening of the tone, and the distressing ascension to the Bs and C:

The first recording of “Casta diva” in G that I know of was in Joan Sutherland’s peerless 1960 recital The Art of the Prima Donna. It’s almost a jolt, after Rebeka’s strained, effortful vocalism, to hear Sutherland so serenely handle the line; the silvery tone just flows blissfully forth, not a hint of plumminess, smooth as buttah:

Singing in the manner as she does here, I think Rebeka might have been advised to do it in F. The cabaletta, “Ah! bello a me ritorna” is ok, with extra points given for not dropping the text as much as others do, but it’s not fleet or flowing with ease.

The duets are a trial. Rebeka and Deshayes’s vibratos are prominent together, and their timbres are too much alike. In the Act II “Mira o Norma,” the explosive attacks on the upper notes are especially unpleasant:

I know it’s frowned upon to dwell in the past, but when you’ve heard the ideal and stupendous, it’s simply hard to forget as a hallmark touchstone. Here are Caballé and Fiorenza Cossotto in the same duet from their complete recording. What I wrote earlier about the singing needing to be purely beautiful is never better exemplified than here: it’s in the original keys, and the long, long breaths in gorgeously bound legati, the joining and exquisite, dynamic tapering of phrases, the utilization of the most lustrously shining, plush and sweet tones – it’s not only heaven to the ears, but its bittersweet pathos makes a devastating emotional impact. I name this rendition as the pinnacle of Bellinian duetting, and the non-pareil standard:

Rebeka’s work is not without some lovely moments, such as a brooding, introspective “Dormono entrambi,” with a long-lined, shimmering “Teneri figli.” “In mia man” is effectively realized, because Rebeka’s manner of attacking the text is in keeping with the highly fraught dramatic confrontation; and though her low notes are not of the booming chest sound, they are firm. The trills, maybe more of a pushed flutter, on low at “Adalgisa fia punita” are acceptably sounded. “Norma non mente,” though, is barked out too defiantly, and the low E flat on ‘te’ is inaudible; the irony and phrase value is lost.

The final two scenes find Rebeka at her most congenial. She, like most sopranos here, is responsive to the text and the music, and she rises impressively, most movingly, to the monumental scope of the tragedy. The two Bs – one in “Qual cor tradisti,” and the other in “Deh! non volerli vittime” – are a bit out of focus, but they could be the expressive motions she’s utilizing. The problem in these final pages is that the soprano is mic’d so front and center, the voice so prominent, that the balance between the other soloists, chorus, and orchestra is strikingly uneven.

The real star of this performance is the conductor Fiore. All the tempi feel just right, the march rhythms and cabalettas not too jaunty nor the slow portions too stodgy, and he appears to be a true collaborator with his fine orchestra, chorus, and especially, the soloists. The textures and beauty of the orchestrations are ideally balanced; there was not a moment that felt off-kilter or ponderously misjudged. The Act I finale really cooks, though maybe a mite more vigor would have been welcomed in the “Guerra!” chorus — I like it done ferociously.

Despite all the felicities of this important milestone in the Bellini discography, it’s proof once again that a truly accomplished Norma is hard to come by. Most of all, I hope Rebeka can find her way back to the vocal state that made her a cherished, and deservedly, highly acclaimed opera star.