Since the Salzburg Festival is mounting only the third production of their opera in their history this summer, I innocently, and rather foolishly, assumed I’d just gather my collected recordings (numbering nine in tutto…two just added since I started researching) and videos (another five), put on my rose-colored glasses, and skim through them in a reverie joyeux. Little did I suspect I’d be entering into combat with a nine-headed Hydra and that the research hole I would fall into would rival the vastness and depth of the sewer system of Paris.

In the beginning there was a play Les Contes Fantastiques d’Hoffmann by Jules Barbier and Michel Carré that used the writer E. T. A. Hoffmann as the protagonist in his own short stories centered on three doomed romantic adventures. First, with the young Olympia who is a mechanical doll. Which all but the love-stricken Hoffmann can see. Then, the aspiring opera-singer Antonia whose physical condition is so fragile she can’t risk the effort of the singing she so loves. Finally, the Venetian courtesan Giulietta who tricks Hoffmann out of his own soul.

Monsieur Offenbach, after seeing the play, toyed with setting it to music until he discovered another composer, Hector Solomon, who was one of his own rehearsal pianists and the man who arranged many of his piano reductions (Judas!), was already working on it. Solomon relinquished the libretto eventually and Hoffmann set to work adapting it first for the producers of the Theatre de la Gaîté, then the Opéra National Lyrique and finally, the Opéra-Comique. Among the many (many) changes along the way were the title role being re-written to accommodate a tenor instead of the originally intended baritone, the three leading female roles tailored for the same soprano (the apparently formidable Adele Isaac), and the Giulietta act moved geographically from Florence to Venice.

It was said Offenbach died with the score in his hand, succumbing to heart failure brought on by gout, a mere four months before the announced premiere. The incomplete Giuletta act was dropped from the first production and its best music sprinkled throughout the score on the opening night. Thus began one of the most complicated and protracted cases of opus interruptus in the history of the lyric theater.

Many hands (so many) have since tried to piece together performance editions including initially Ernest Guiraud (who did a similar service for Bizet’s Carmen after that composer’s untimely demise) and the Choudens publishing house. Then Andre Bloch in 1903 for the Monte Carlo opera, later Tom Hammond of the Saddler’s Wells, and later still Richard Bonynge (in service of you-know-who). In the 1970’s Fritz Oeser was given access to thousands of pages of additional materials discovered by the Offenbach heirs. Still more material was discovered in the ‘80’s which is when Antionio de Almeida, Jean-Christophe Keck, and dearly departed parterre commenter Michael Kaye (QuantoPainyFakor) got involved. So, Hoffmann has become the proverbial box of operatic chocolates since when you tuck in, in the theatre or at home, you never know what you’re going to get.

Yours truly inadvertently saw the premiere of the first Kaye edition on opening night of the 1988 season of LA Opera with Placido Domingo and Julia Migenes-Johnson. I recall leaving being fairly incensed and surprised at the loss of both the great Septet (not written by Offenbach and really just a re-fashioning of the famous ‘Barcarolle’) and the loss of the baritone’s big aria ‘Scintille, diamant’ (ditto). Still, there wasn’t a sign in the lobby warning us that some of the best bits will be missing. I do remember that the big trio in the Antonia act with Dr. Miracle and the Voix du Mere gave me gooseflesh in the theater.

When it comes to recordings we can easily dispatch the first high-profile EMI recording produced by Walter Legge in 1965 and led by Andres Cluytens. Nicolai Gedda does his best against three separate sopranos: Gianna D’Angelo (who is dull-ish) as Olympia, Victoria de los Angeles (who struggles with Antonia’s tessitura – reports are she was un-well), and Elizabeth Schwartzkopf as an amoral and opportunistic woman of easy virtue (who is miscast vocally). They further complicate this enterprise by giving the role of Nicklausse to a baritone. I’m sure I don’t know what they were thinking.

Sadly, during my research, I learned that this project had been intended for Maria Callas to sing all three heroines. Before you get too excited, I’ll remind you that 1965 was the very tail end of Madame’s career, so perhaps it’s best we (and she) were spared. Still, in an earlier day, it would have been a perfect showcase.

Then we have the justly celebrated Decca set from 1971 where Bonynge, following Sadler’s Wells tradition, removed the recitatives composed by Giuraud in favor of dialogue adapted from the original play. It saves oodles of time, but then Offenbach’s planned ‘grand opéra fantastique’ reverts back to an opéra-comique when he had already written a hundred of those. We have a heroine(s) in Joan Sutherland who manages to encompass the vocal demands of all three roles with relative ease. Unsurprisingly, she is the very best Olympia of all (and there’s an alternate take of “Les oiseaux dans la charmille” on the ‘La Stupenda’ collection taken at a dizzying tempo). She’s a little more than you need for the vulnerable Antonia but she, Gabriel Bacquier as Dr. Miracle, and Margarita Lilowa as her mother’s voix deliver the best and most hair-raising trio of all. Sadly, in the Venetian act La Dame Joan sounds like your maiden aunt in the dialogue. No vamp, she. Bacquier does very well by all the heavies and Huguette Tourangeau is a fruity Nicklausse.

This is the first of four commercially released recordings with Placido Domingo as the poet hero and he was only 28 when it was made, which is impressive in retrospect. He’s brash and his French is adequate, plus he’s extra sloppy on the romanticism. Hoffmann is an absolute bear for any tenor to sing because any time he opens his mouth he never shuts up. The romanza section in the middle of ‘Kleinzach’ is like a litmus test to show how the tenor in question will make it through the evening.

Bonynge generally keeps things moving with his Orchestre de la Suisse Romande who are French-adjacent but I wouldn’t call his reading especially piquant. He re-orders the acts so Antonia is last under the determination that it has the best music and downgrades the big septet, dropped into the epilogue, into a quartet with extra high notes pour Madame. Most of the supporting cast speaks French which is a plus and they have the very best Andres/Cochenille/Pitichinaccio/Frantz in the great Hugues Cuenod.

By some wild coincidence (slaps hand to cheek) the very next year a rival set was released by Westminster starring America’s sweetheart Beverly Sills as the heroines and Norman Triegle as the guy trying to kill her. This also happened to coincide with a brand new production at the New York City Opera mounted for the two by Tito Capobianco and designed by Ming Cho Lee. Unfortunately, it’s a little like Hamlet without the prince. Stuart Burrows is perfectly adequate as Hoffmann, but nothing more. The supporting cast is almost all British and Julius Rudel leads the London Symphony Orchestra well enough.

Ms. Sills stated more than once that she wasn’t a ‘recording studio’ singer (some love it and some don’t) and she proves it here. She’s not bad by any stretch, but when you hear the live performance released by VAI from New Orleans with Treigle and the Quebecois Tenor André Turp from 1964, you hear what you’re missing. She needed the excitement of an audience. She also needed to be the white-hot center of attention apparently. In my exhaustive (I’m exhausted) research, I discovered that at the first run of that new NYCO production the opera ended with the Antonia act. No epilogue in the tavern. It was reinstated for the revival 3-years later (without La Sills). Still, I wonder who broke the news to the tenor? Plus, I can’t imagine that was Capobianco’s idea either.

Then, suddenly and inexplicably, the trail went cold. What with the birth of digital sound and the record companies rushing to re-record their entire catalogs, you’d never guess we had to wait a whole 18-years – until 1988 – for another commercial release. But the next one was a doozy and on a whopping three discs (all the previous had been on two) with a 350 page booklet as thick as the double jewel-case. This was the critical edition of Fritz Oeser and it came with more music that we’d ever heard before, most especially for the Venice act but with the Septet and Dapertutto’s “Scintille, diamant” relegated to an appendix on disc three. Still, the acts were back to the composer’s intended order, so you can’t have everything. Plus, this version was capital ‘G’ grand, perhaps to its own detriment.

Sadly, Sylvain Cambreling conducts the whole affair like he’s following the score with a magnifying glass. We get all the extra music for Nicklausse/La Muse (a wonderful Ann Murray) with the gorgeous apotheosis finale and the Venetian act fleshed out considerably with music that wandered in from Offenbach’s Die Rheinnixen (which is where the ‘Barcarolle’ originated, so…). Neil Shicoff makes a wonderful, ardent Hoffmann and he’s got everything you want, plus a suicide edge to his singing that Domingo completely lacks. As his nemeses we have Jose van Dam and I don’t want to listen to anyone else in these roles. He’s magnificently malevolent and somehow sexy all at the same time. Luciana Serra is stiff (too mechanical?) as Olympia and Rosalind Plowright is a little too vibrant for Antonia (I also don’t think the EMI engineers did her any favors). The only hard fail is the choice of Robert Tear as all the servants, as he’s completely charmless.

But the glory of this set is the Giulietta of Jessye Norman and I think it’s one of the best things she ever did. The sexiest barcarolle ever and her French is exquise. She puts the Fatale in Femme. She and Shicoff tear the house down in the fullest, most satisfying, version of the ‘Mirror duet’ I’ve ever heard complete with gong finale; it’s such a vocally taxing piece, for the tenor especially, that I’ve never heard a live performance where you get the repeat of the verse, even though Oeser and Kaye both lowered the tenor’s line in the duet so he’s harmonizing and not up top with the soprano. I watched a video from Covent Garden recently where it was so truncated that the audience was stunned into a half-hearted golf clap when they realized it was over. Jessye is absolutely gala and I especially love the little aria she gets, “Qui connaît donc la souffrance,” in which she bemoans her gilded existence.

Deutsche Grammophon answered back two years later in 1990 to all that scholarly erudition with all the star power they could muster with a complete return to the Choudens version — back to two discs with very little recitative. From the same company that in 1984 brought out an exhaustively curated French version of Verdi’s Don Carlos, go figure. Seiji Ozawa leads the Orchestre National de France with Domingo returning to the studio after twenty years in a favored role and in his mature prime (as a tenor). The villains were relegated to four different singers, none of them particularly successful, I’m sorry to say. However, we do get one very lovely heroine in Edita Gruberova. Perhaps closest to what Offenbach intended, her singing is so bewitching at times you’d think she was, indeed, French, and she’s so musically scrupulous it’s unfortunate that her vowels betray her here and there. We get a hilarious Frantz from Michel Sénéchal and delicious luxury casting as La voix de la Mère from Christa Ludwig. The French orchestra and chorus makes a difference here and the sonics are particularly seductive after the EMI-dry spell.

In 1992 Phillips threw their hat in the ring with the first of two recordings of Michael Kaye’s critical edition. This one using dialogue (?) and it’s more than a little disappointing all-around. The heroines are parsed out to a clockwork Eva Lind as Olympia, Jessye Norman as Antonia (who has tessitura problems in this role…whoops), and Cheryl Studer as the newly exhumed coloratura Giuletta. Samuel Ramey as the villains has that gorgeous voice but an almost total lack of subtlety and no sparking diamond. Francesco Araiza as Hoffmann is solid, but doesn’t make my heart go pit-a-pat in the slightest. In keeping with the scholarly erudition no septet either. Blah.

Same problem with the Opera National de Lyon version, led by Kent Nagano, released by Erato that followed in 1996. Here, at least, we have a French Hoffmann (enfin!) but the very young (33 yrs.) Roberto Alagna drives his lyric instrument too hard and it’s not pleasant at times. He’s singing on his principle not his interest. Although we’re still denied the diamond aria we get a frisky, Folies Bergère-style version of the Septet with Sumi Jo yodeling along as a sprightly, pointillist, Act IV Giulietta with Natalie Dessay (on the cusp of stardom and sporting stratospheric interpolations) and Leontina Vaduva (remember her before Angela Gheorghiu happened to Roberto Alagna? Now there’s a story!) rounding out the ladies. Plus, a completely French speaking supporting cast with Baquier and Sénéchal filling in as Spalazani and Schlemil. We have recitative again, mixed with dialogue, and it’s interminable (Mr. Kaye, make up your mind). Jose van Dam is back as the villains and at 56 yrs. olds he’s still got it even if he’s leaning a little more on the texte than the voix.

Due to the newly discovered material, since the last new edition, we get little bits tickling our ear for the first time here and there, like more ‘Glou, glou, glou’ in the tavern and a much longer introduction to the Barcarolle, then an almost complete overhaul of the Venice act which lacks the previous versions’ feeling of foreboding. The orchestra and chorus are absolutely glorious, as is the engineering, and Nagano has a beautiful light touch, perhaps too light since in spite of the recit. It sounds like an evening at the Opéra-Comique not L’Opéra.

The previous year there was a video release of this Lyon production entitled “DES Contes d’Hoffmann” which, due to the director’s concept, staged the whole thing in an insane asylum (an all too common conceit with this piece now). The tenor is completely different but Dessay (going even higher into the ledger lines, if you can believe it) remains while a lot of music goes missing. It’s criminal. The only reason to own it is Barbara Hendricks in a rare video appearance who is absolutely stunning as Antonia.

Now, finalement, we get to my two favorites. Andre Cluytens’ first recording (which was probably why he was entrusted with that second EMI catastrophe) and it’s all Choudens naturalment. Released in 1949 on 32 French Columbia 78 sides, it has survived very nicely to a very clean digital transfer. Raul Jobin leads an experienced and flavorful French cast and orchestra and no one puts a foot wrong. It has a real feeling of theatricality and excitement about it, which almost all of the above lack, and deserves to be heard more often.

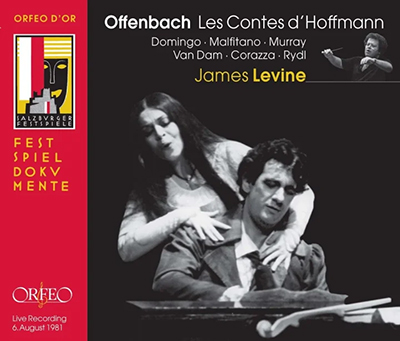

But my most favorite is actually a live relay from the Salzburg Festival August 1981 from the revival of the super-spectacle Jean-Pierre Ponelle designed and staged there in the massive Grosses-Festspielhaus with James Levine conducting the Vienna Philharmonic. It’s pretty much Choudens all the way, as well with Guiraud recits.

Placido Domingo was by then finding Hoffmann a very congenial stage role and Covent Garden had just mounted their new production for him earlier that year with the Met following suit the next. He’d continue in the role for more than a decade. The first year in Salzburg he was partnered by Edda Moser (about whom the critics weren’t crazy) and Jose van Dam in his absolute prime as the villains.

The staging was a cinerama spectacle using all of the famous Salzburg machinery and got tightened up the second year, much to the critics’ approval. The other major change was that Catherine Malfitano stepped in for some performances and the radio relay was issued on the Orfeo label in 2009. In spite of its fairly international cast, it does have a gripping theatricality about it. Everyone is on top of their game and Malfitano may be the most ideal interpreter if you’re looking for the three-in-one combo. Olympia is a stretch on the very top, but she’s the only singer who really commits to the echo effect in the aria all the way through. Her Antonia is harrowing (with a great dying trill) and she’s a sultry Giulietta; a very fine artist who’s individual in everything she does. I didn’t appreciate her when her career was happening because I didn’t know better.

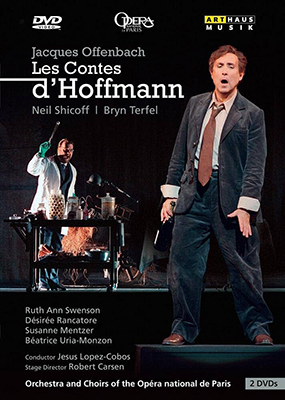

Three commercial videos deserve honorable mention. Niel Schicoff from the Paris Opera in 2003 in a one of the spartan extravaganzas Robert Carsen specializes in. Desirée Racantore, Ruth Ann Swenson, and Béatrice Uria-Monzon are the ladies. Jennifer Larmore gets plenty of music as the Muse/Nicklausse and Bryn Terfel menaces as the villains. It’s Choudens with add-ons and magical all the way around.

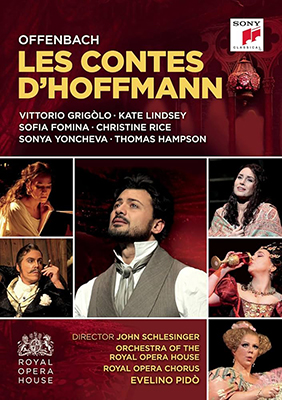

The justly famous Covent Garden production mounted for Domingo was revived for Vittorio Grigolo in 2017, streamed into cinemas, and released on DVD and Blu-ray. It’s hyper-traditional with a strong international cast and still works in spite of Thomas Hampson’s villains, which are self-conscious.

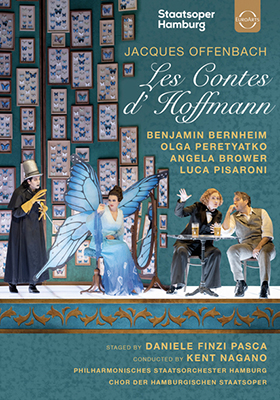

Then, a more recent 2022 performance from Hamburg led by our friend Kent Nagano with Benjamin Berhnheim and Olga Peretyatko in the leads. Luca Pisaroni gets done up with Nosferatu fingers is very good but not ‘echt’ and the staging is a little too Cirque du Soleil for me. Still, the music making is very solid and Bernheim is cause to celebrate.

Some of the recordings above may be hard to lay hands on, especially the Orfeo and the original Cluytens. I want to point you all in the direction of your local libraries on-line apps. Most subscribe to either streaming services Kanopy or Hoopla which allow you to borrow a number of items each month. My Hoopla has been invaluable during the research for this piece as I had never heard the Cluytens before at all. Not only do they have the whole live Orfeo series onlin,e but most of the Opera Rara recordings as well as almost the entire catalogs of Decca, DG, and Phillips. If I had known it would all be at my fingertips one day, it’d be easier to find a place to sit.

Now I’m not one to stand up for hoary tradition, per se, but it seems a shame to me that the Septet (in whatever form it takes) and Dappertutto’s aria are left out. They’re both exciting moments that we’ve all come to be used to. Plus, where else are we going to hear them? Banishing them from the score is banishing them completely. Adding to that is Offenbach’s reputation as an infamous tinkerer with his shows, so I’d rather have the thoughts of Giraud (who was of Offenbach’s era) augmented by scholarly erudition. Hence my preference for the Salzburg relay.

The thing that seems clearest to me is that a sense of theatricality helps above all else with bringing Hoffmann’s many loves to life. Having better-than-average singer’s French and a good grasp on the style doesn’t hurt. None of these are perfect, but they’re all enjoyable for one reason or another. Bon appétit!

Photo: Emilie Brouchon/OnP