It is also about visual representations of power; as our own Callum Blackmore said in his 2019 review, Kevin Pollard’s resplendent costumes playon a timeless aesthetic, at once Egyptian, Edwardian, and Elizabethan… hinting at a kind of eternal majesty.

To me, the Act I scene of ceremonial dressing, presenting Akhnaten as at once frailly human and perfectly smooth, polished like a carved doll, before wrapping him in unimaginable splendor is all about this: what does power look like? What has is always looked like? How does it refer to itself visually throughout history, connecting across time and cultures?

It’s also about texts, history, the way that language shapes understandings of history and the ways that gaps can—and perhaps should—remain unfilled. Glass’s libretto presents itself as a variably opaque archive, a collage of documents in languages that often remain untranslated. How much can we know about this man who was also a god-king?

Here vision takes on a new dimension; Glass is clearly skeptical about the limit of historical knowledge, but at the same time, finds himself in the powerful but uncomfortable position of the arbiter of a different type of sight, controlling our understanding of what we’re hearing at all times.

The brief framing device at the start and end position historians as invasive inspectors, stagers and directors of narrative, brings this discomfort to the fore. Texts in Akkadian, Egyptian, Hebrew, English, along with long wordless stretches make understanding a slippery thing; we may know what’s happening, but only because we are told in summary; the long stretches of untranslated or wordless singing become everything we cannot know about history, the spaces between the lines of the texts.

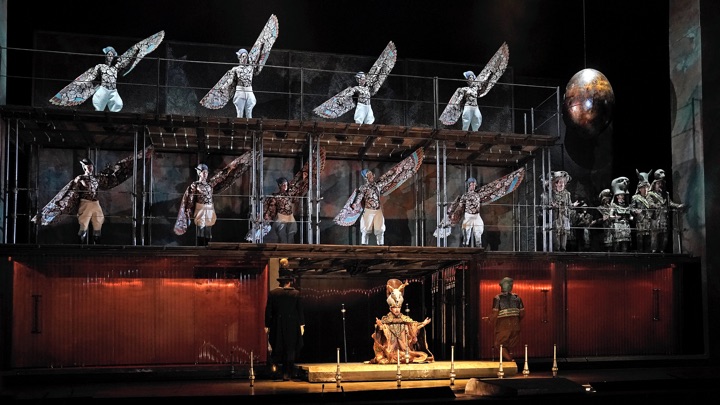

Phelim McDermott’s production and Tom Pye’s marvelous sets take these questions of vision seriously; notice when the stage appears flat, people appearing as successions of static images. Notice again when that flatness gives way to subtle movement, to emotion.

Notice when images turn into each other, morphing like Philip Glass’s shifting-sand score; eggs turn to eyes turn to juggling balls turn to the sun which falls down to earth, only to be rolled across the floor like a toy. What can we see when we look at these ancient images? Where does the symbol end and the human begin?

So, how did it hold up after three years back in the pyramid? Very well indeed, though some of the initial spell-binding shock did not return with full force, Karen Kamensek’s direction was crisp and cutting, especially in Act I, which stretched the wings of Met Opera Orchestra to bring forth every possible bit of color and shading, to stunning effect.

But the second act featured some weird tuning issues—especially in the brass—and other little glitches which briefly marred the otherwise excellent playing last night. They regained their surety by the third act, however, locking back in Glass’s groove.

Anthony Roth Costanzo’s performance was grittier, more tenuous, and more interestingly flawed than I remember from 2019. Moments of splendid lightness and effortless ethereality would be interrupted by harshness, an occasionally even strained sound.

From a character standpoint, it works to humanize the pharaoh, vocally dramatizing his conflict between head-in-the-clouds religious fervor and human concerns, divine kingship and frail mortality, but big voice-nerds will most certainly note it.

For me, it did little to detract from the night; Costanzo brought a mournful, enigmatic motionlessness, able to use every inch of his small frame and sculpted face to give the impression of a statue that comes in and out of life, both unknowable and sympathetic, childlike and immensely powerful.

Rihab Chaieb (succeeding J’Nai Bridges) had a rich sound that emerged more and more fully as the night progressed, but perhaps because she is a new addition to the static world of Akhnaten, I found her lacking in the physical gravitas necessary to pull off such mesmerizing stillness and muscular, slow-motion movement.

In the second and third acts, however, her voice took on an increasingly easy grace and power, beautifully weaving together with her six daughters () and mellowing Costanzo’s brightness with round, honeyed tone.

It was truly Dísella Lárusdóttir’s night, though. Her terrifyingly beautiful sound, powerful and cutting (more biblical angel than airy-fairy) and mesmerizing physical intensity made it impossible for me to take my eyes from her; even her silent interactions with the spirit of her dead husband, Amenhotep III (Zachary James) were infused with a seemingly unlimited stream of power, her eyes blazing with the frightening surety of a true fanatic.

James was the other leading man last night; his zealous delivery and nearly overwhelming physical presence threatened to steal the show, along with Lárusdóttir. Upon second viewing, I believe this character, who shifts from father to scribe to general to historian, makes or breaks the entire show.

James’s ability to strike the perfect balance of immense, otherworldly power within the hyperbolic ancient language, never veering in pompousness or priestly monotone, is absolutely necessary to the creating Glass’s Egyptian world and to making it sufficiently strange enough to hypnotize. He’s scarily good.

Returning also were Richard Bernstein, Aaron Blake and Will Liverman as Aye, the High Priest of Amon, and Horemhab, who acted as king-makers and king-slayers and made for a richly woven, textural trio. Bernstein’s stentorian, markedly-rich bass emerged triumphantly in the Act I funeral scene, while Blake wowed in the Act II chorus, his “Amens” blasting forth with ringing confidence.

The direction and choreography remain the triumphs they were three years ago. For the leads, it is a masterclass in the power of stillness, while the brilliant Skills Ensemble (choreographed by Sean Gandini) acted as a mysterious life-force diffusing throughout the slow-motion scenes.

What a brilliant success for the Met in 2019 and again now. Even with some little hiccups, this revival proves that nothing about the success of this production was a fluke or a gimmick.

Unlike so many of the drably expensively productions that have premiered in the last few years, and unlike the superficially lavish ones of a few decades ago, Akhnaten has something interesting to say, and in so doing, makes a convincing argument for big-budget productions in which every single cent was spent to create thought provoking, intelligent art that is also breathtakingly beautiful, eerie, and striking.

Photo: Ken Howard / Met Opera

Comments