Como’s unerring good taste is even present in the most familiar sacred hymns, one such as “Abide With Me,” which gains by utilizing a reverential, “spiritual” tonal quality, but without emotive preciousness:

By way of a contrasting example (and please indulge me in this rather odd digression), though

it’s perhaps unfair to make comparisons among singers who have completely different kinds of voices in dissimilar genres, but I can’t help but wonder (and I am critical) at the discretion and ability of some opera singers who simply can’t (or won’t learn to) tonally lighten up and adapt their voices when needed for like material, to lose the bombast and ballast.

Many years ago I acquired Jerome Hines’ album of sacred songs and hymns, and I found it a trial. In particular, in one of my favorite songs (learned from Jeanette MacDonald in the movie San Francisco), Adams-Weatherly’s “The Holy City,” Hines’ heavy, rumbling, lumbering manner is hard to take; too, the vowels are bloated and distorted.

Look, Hines was a deeply religious man, his intents were sincere, and this music obviously has great meaning to him. Nothing personal.But this Fafneresque, Fee-Fi-Fo-Fum approach for music that requires some modulation, some—dare I say it? —delicacy of approach , Hines does it a disservice. Some may argue that Hines had a big, heavy bass voice trained for the repertoire he undertook.

But recently I was listening to the EMI De Sabata set of the Verdi *Requiem*—Cesare Siepi singing the bass part. I was marveling at how, in the “Lacrymosa,” “Hostias,” and “Lux aeterna” sections, Siepi fines down the tone with a liquid, slender-soft beauty as befits the music (and Hines, under Cantelli, can’t or won’t modulate the tone).

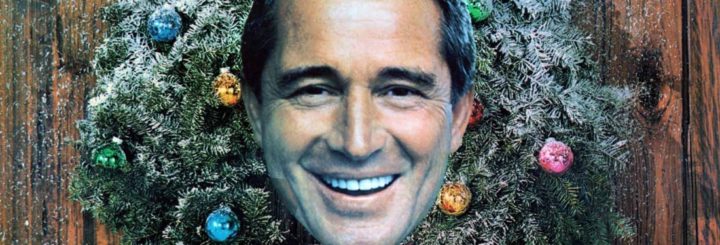

Christmas music. What we once took for granted we now look back: Frank, Ella, Judy, Nat, Rosemary, and Perry, etc—they handled Yuletide music with sophistication and style. You could even look to opera singers of the past who put out respectable collections. I am way too polite to list current ones (cough, coughmann) who’ve put out collections that are highly, shall we say, variable.

Despite the intrusive (and unnecessary) backing chorus, Como turns in an eloquent rendition of “O Holy Night.”

Even the most tiresomely familiar “Santa Claus is Comin’ to Town” can be done stylishly, minus the cutesy-poo effects:

Como reminds us of what a beautiful number “Silent Night” is, especially when as sensitively sung as this:

The piece that intrigued and moved me the most, though, and the biggest surprise in its existence is Como’s rendition of the cantorial, Hebrew-Aramaic “Kol Nidrei.” Previously, I had never heard of this piece. I turned to Wikipedia for information:

“Kol Nidre /?k??l n??dre?/ (also known as Kol Nidrey or Kol Nidrei (Aramaic: ???? ???????) is an Aramaic declaration recited in the synagogue before the beginning of the evening service on every Yom Kippur (“Day of Atonement”). Strictly speaking, it is not a prayer, although commonly spoken of as if it were. This dry legal formula and its ceremonial accompaniment have been charged with emotional undertones since the medieval period, creating a dramatic introduction to Yom Kippur on what is often dubbed “Kol Nidrei night”, with the entire Yom Kippur evening service popularly called Kol Nidrei.”

Along with the text and translation:

Ve’esarei, Ush’vuei, Vacharamei, Vekonamei, Vekinusei, Vechinuyei.

D’indarna, Ud’ishtabana, Ud’acharimna, Ud’assarna Al nafshatana

Miyom Kippurim zeh, ad Yom Kippurim haba aleinu letovah

Bechulhon Icharatna vehon, Kulhon yehon sharan

Sh’vikin sh’vitin, betelin umevutalin, lo sheririn v’lo kayamin

Nidrana lo nidrei, V’essarana lo essarei

Ush’vuatana lo shevuot.(All vows, and prohibitions, and oaths, and consecrations, and konams and konasi and synonymous terms, that we may vow, or swear, or consecrate, or prohibit upon ourselves, from the previous Day of Atonement until this Day of Atonement and …from this Day of Atonement until the [next] Day of Atonement that will come for our benefit. Regarding all of them, we repudiate them. All of them are undone, abandoned, canceled, null and void, not in force, and not in effect. Our vows are no longer vows, and our prohibitions are no longer prohibitions, and our oaths are no longer oaths.)

This, by Cantor Avraham Feintuch, might be considered an authentic rendition:

Scouting around online, I discovered that Como’s 1953 version, though not strictly authentic, is held by Jewish people with great affection and reverence; some of the testimonials to it are deeply moving. Particularly in America, after the Holocaust, this generosity of spirit by a man who was a devout Roman Catholic was a clear message of welcoming and acceptance. Moreover, Como would sing this on television for Yom Kippur.

This opened my fascinations, so to speak. I listened to other versions, including those by Al Jolson in “The Jazz Singer,” Jan Peerce and Richard Tucker, as well as a few names I didn’t recognize; they are vastly different in approach. I consulted with my friend Kedem Berger, who is based in Israel, and asked him about Como’s performance. Results: impressive, beautifully sung. The Hebrew/Aramaic fairly good, Askenazy accent, vowels and consonants a bit droopy; the “softer” approach not usual—the more assertive, highly dramatic, somewhat nasal style is the norm—providing a more “chiaroscuro” sound.

Here, too, you will find Como actually singing the closest thing to what you call coloratura—impressively handled, smooth scalar passages:

If this doesn’t make Como cool as hell, I don’t know what will.

Comments