This is equally true of concert readings of Elektra such as the Boston Symphony Orchestra’s 2015 concert under Andris Nelsons starring Christine Goerke. The Metropolitan Opera has been having a strong (if uneven) season and this year’s revival of the 2016 Patrice Chereau Elektra production was greeted ecstatically at the curtain calls.

The Metropolitan Opera Orchestra played superbly for Donald Runnicles with controlled brass playing and well-defined string playing. Runnicles balanced power with subtlety keeping the orchestra level just beneath the singers to carry them without covering their voices. He also was very dramatic but kept the intensity just below boiling point rising to shattering climaxes in the final scenes in a long slow crescendo.

Vocally, the evening started well with a strong quintet of maids with not one geschrei among them. Alexandra LoBianco, a Turandot in major venues throughout the U.S., made a fearsome Overseer with strong bright tones. Tichina Vaughn has been a fine (if late) acquisition to the Met, her First Maid displayed a rich, solid contralto.

Eve Gigliotti and debutantes Krysty Swann and Alexandria Shiner displayed strikingly distinctive and radiant voices one wanted to hear in more musically rewarding roles. Veteran lyric soprano Hei-Kyung Hong returned in a moving cameo as the Fifth Maid (conceived here as an elderly woman and probable former nurse or nanny to Elektra).

Hong began tentatively with muffled tones but rose to radiant high notes at the climax to her apostrophe in defense of Elektra. Unrecognizable with grayed hair, Hong was a touching presence later on as she recognizes Orest before Elektra does.

Bass-baritone Greer Grimsley also sported his own gray hair as a slightly gruff but very human Orest. Initially remote and mysterious with a darkly opaque tone, upon Orest’s recognition of his sister his tone and manner became warmer and more emotional ending in a loving embrace.

Stefan Vinke, such an impressive Siegfried in the last iteration of the Lepage Ring, returned in the much less demanding role of Aegisth blithely indifferent and businesslike in his demeanor with a bright tenor sound.

Michaela Schuster returned as Klytämnestra, the role of her 2018 Met debut, in a more authoritative and commanding reading. Her take on the guilty queen is more conventional than that of the elegant Waltraud Meier who played her as a sad, regretful woman not a grotesque monster.

Schuster dug more into the paranoia and fear highlighting Klytämnestra’s febrile changes of mood from motherly beseeching to furiously lashing out at Elektra. Schuster’s mezzo-soprano isn’t the richest or most beautiful vocal timbre around but she is a subtle delineator of text and phrase making each moment tell.

The Norwegian rising superstar soprano Lise Davidsen returned as Chrysothemis for her third and last role in this breakthrough season. Very natural and convincing onstage, Davidsen’s Chrysothemis initially seemed cowed and submissive to her sister’s bitter invective against her.

Interestingly, the tables turned in her solo “Ich kann nicht sitzen…” which revealed the seething inner torment and angry desperation of the seemingly demure younger sister. Davidsen’s tone is columnar showing strength in all the registers with darkly complex middle and lower registers seamlessly rising to a steely penetrating top register. Her timbre is cooler and darker than that of the warm and golden-toned Deborah Voigt.

Davidsen’s vocal line highlights the angular contours of the music rather than the soaring high phrases creating a more rebellious, neurotic character. Her tone has more metallic cut than Nina Stemme’s as Elektra and easily surmounted the massive orchestra without strain. The angry intensity of her delivery and searing top notes show evidence that the makings of a future Elektra are already there.

Nina Stemme returned as the title protagonist after creating this production at the Met in 2015. She is now seven years older and will turn 59 next month. Yet the tone is completely free of wobble, the core of the tone is warm and round with inherent nobility – Elektra is a royal princess and not just a shrieking virago.

Initially Stemme seemed to have some trouble with her top which seemed to be eroding with unfocused tones that lacked defined pitch. Her phrasing and vocal production favors long legato lines rather than angular declamation. Though her sound is a little drier with less power than formerly, Stemme managed to project her tone over the orchestra through tonal density rather than metallic thrust.

The Swedish soprano’s Elektra, now as in 2015, shines more in the duets with her sister, mother and brother than she does in her solos. Elektra’s opening monologue “Allein!” suffered from blunted high notes which continued through her dialogue with Klytämnestra. Stemme’s Elektra started to catch fire in her second duet with Chrysothemis where there was no doubt she could hold her own against the younger heroic-voiced Davidsen.

But it was the beautiful Recognition Duet with Orest where Stemme truly came into her own. Her tone was full of mournful beauty with supple legato phrasing. Her upper register seemed to bloom more freely and this continued until the final curtain.

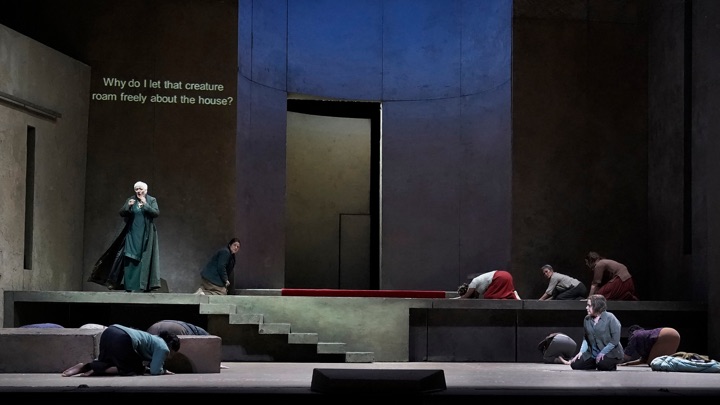

The late Patrice Chéreau‘s direction (recreated by staff revival director Peter McClintock) emphasizes emotional ambiguity and internal conflict in the family relationships. Klytämnestra holds and caresses Elektra during their bitter confrontation consoling her like a child. Orest falls to his knees and embraces Elektra despairing at what the murder of their father has done to her. Chrysothemis and Elektra stalk and pace around each other like wary cats but also embrace like sisters. There is love beneath (or co-existing with) the hate.

Chereau’s production is more cerebral than melodramatic and Stemme’s somewhat reserved, calculating Elektra fits well into this concept. Stemme’s Elektra always seemed the sanest individual onstage never quite giving over to obsession or hysteria with a good line in mordant sarcasm and contempt. Her Elektra leads from the head not the broken heart or damaged soul.

At the end of the evening, this Elektra does not fall dead onstage from exhaustion but stares vacantly into the distance. Her triumphant dance is merely in her head in a total retreat from reality. Her death is internal.

However, what I have left out is the factor of onstage chemistry – the whole outweighed the sum of the parts. Runnicles’ blazing conducting, the excellent orchestral playing, Davidsen’s youthful brilliance, Schuster’s canny artistry and veteran authority, Stemme’s humanity and intelligence and Chérau’s provocative if somewhat alienating production coalesced into something powerful and elemental emanating from the music.

And once again the audience erupted into frenzied applause which seemed to last for minutes.

Photos: Ken Howard / Met Opera

Comments