What Lemmons, Blanchard, and Liverman have achieved in the character of Charles is extraordinary. I can’t think of anyone else like him in opera, not only because of the lack of Black characters written by Black people in the repertory, but also because of Charles’ particular status as a victim of sexual assault. Men in opera are so rarely allowed to be vulnerable, to need, indeed to have any complex emotions. Rarer still is a depiction of a victim like Charles, who is given space to feel the ugliest feelings about the assault, whether worrying that it was his fault or subtly interrogating how this event impacts his own sexuality, while also retaining a silvery thread of lightness, an ability find moments of happiness.

Charles is a peculiar hero; he’s sweet, smart, and open, but has none of the easy charm of his father or brothers; he’s lonely, often sullen. He can freak people out, as his interaction with college girlfriend Greta in the third act demonstrates. Charles is a gaping maw of need, even before he undergoes deep trauma at the hands of his abuser. He aches for connection, latching on to anyone around him, spilling his guts out. He craves love, and when he asks for it, he’s rejected over and over again. Lemmons reminds us constantly; the south is no place for someone like him. If only the world were able to rise up to meet him, to give him the love and intimacy he deserves.

All around him are examples of men so unlike himself—they’re smooth talkers like his father Spinner (Chauncey Packer, giving us a golden tenor sound and saccharine, sleazy charm), boisterous boys’ boys like his brothers, or at worst, disgusting abusers like his cousin Chester (Chris Kenney, pulling off a monster of a part with aplomb) who sexually assaults him when Charles is seven. He is haunted by all of these men, by masculinity itself, as the ballet that begins the second act makes manifest. Everyone is trying to impress on him what it means to be a “real man.” Charles is told, again and again, to throw off the part of himself that needs love and connection, that feels pain and asks for comfort.

But in the end, he chooses to love, and connect, and to hurt anyway. He quotes his mother: “Sometimes, you just gotta lay it down in the road.”

Liverman was subtle, prickly, heartbreaking, and transcendent, with a powerful dramatic range and voice absolutely resplendent with color. This role shows him as an artist capable creating fascinating, realistic characters while retaining complete control over his instrument, which he wields like a champion fencer. He’s at his best vocally, though, when Blanchard’s score allows him to pull off the gas pedal a bit.

The second and third acts give Liverman a chance to swap his powerful, flinty baritone for something more nuanced, a creamy sound with a hint of coldness and haunting desolation. I cried steadily through the third act, where Charles finally breaks down, only to find himself rejected once again. The man sitting next to me, wiping his own eyes said, “You too, huh?” (How I missed being at the opera!)

Blanchard and Lemmons understand with perfect clarity the range of cruelties— from casual to catastrophic—imposed on children, especially Black children, and how pain and rejection can often come from those closest to us. Yet, in Charles’s relationship with his mother Billie (Latonia Moore), he finds that flawed, human love can be , to point his hopes towards his future.

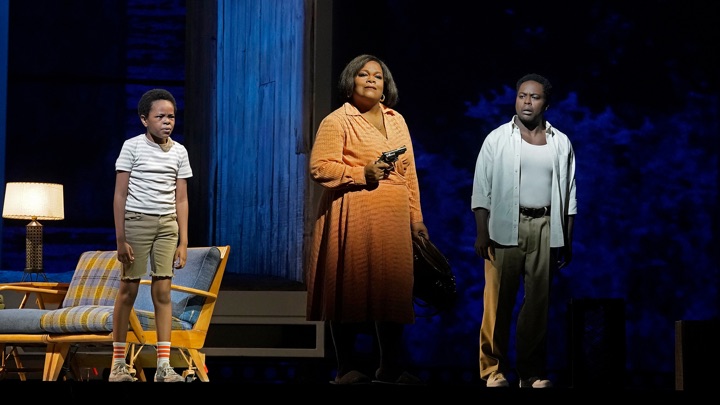

Moore triumphed as audience-favorite Billie, a character who felt uneven for me at the beginning, as she swung wildly from a gentle, exhausted mother to a jealous wife waving a pistol at her philandering husband. As the opera proceeded, however, Moore was able to deftly bring these disparate characterizations together, presenting a complex, imperfect woman whose love for Charles centers them both. Moore was a vocal powerhouse here, her gigantic soprano shaking the whole house, and her on-stage chemistry with Liverman was palpable, providing one of the most touching and complicated mother-son dynamics I’ve seen.

Angel Blue, who continues to be, in my opinion, one of the most interesting singers working today, took on three roles last night, personifications of Destiny and Loneliness, as well as Charles’s college girlfriend Greta. Blue, whose upper registers spins like a top and who imbues romantic characters with staggering intelligence and humanity, was not always given a chance to show off her unique qualities here, with so much material sitting in her low and middle voice. But as Greta in the third act, Blue (dressed in a fetching powder blue ’80s pantsuit) brought the out the shading in her magnificently balanced sound in a brief love scene, showing her as at once desiring, frightened, and guilty.

The cast list is quite long, and thus time doesn’t permit me to compliment every singer in the way they deserve, but let me call out a few here. Ryan Speedo Green, as Charles’s Uncle Paul, brought a perfectly rounded sound, warm and bright with a well of richness to support it. I only wish he had more music, because Blanchard’s writing suited him perfectly. Brittany Renee as Evelyn offered a uplifting lightness, a lovely, crystalline soprano that was all youthful excitement. More from her please!

As Charles’s brothers, Calvin Griffin, Terrence Chin-Loy, Errin Duane Brooks and Norman Garrett brought humor and a lovely array of voices well-matched to one another. (More from them as well!) And finally, Donovan Singletary, who had only two scenes in the whole show, first as a Baptist pastor and then as a terrifying frat brother, positively shone, with a clear, glinting bass-baritone and a magnetic physical presence. (Put him in everything!)

Blanchard’s score is richly colored and beautifully orchestrated, imbued with moments of humor, but mainly with a clear-eyed compassion for his characters, to whom he never condescends nor condemns. The lyrical moments, which increase over the course of the opera, are tempered beautifully by moments of discomfort.

The blend of classical and jazz styles is seamless; Blanchard’s familiarity with a range of idioms and his ability to tie them together into a was a triumph, with a church sequence with gospel chorus melting into an impressionistic forest scene, and a stunning, lengthy stepping sequence for the corps of fraternity brothers leading to a touching love duet. The step-dancing received a standing ovation in an outburst of joy and pride, especially from the Black audience members around me. I heard more than one person around excitedly declaiming, “Now that’s what I want to see in an opera.”

Finally, the Met orchestra were in fine form last night, with Nézet-Séguin (who I think particularly excels with newer works) summoning a beautifully textured performance, highlighting the brilliance of Blanchard’s score and energizing the entire house. He also looked positively overwhelmed with joy, like at any moment he might levitate up and away from the podium. By the end of the opera, so did I!

Photos: Ken Howard / Met Opera

Comments