There wasn’t much documentation yet on YouTube then, but Davidsen’s “Dich teure Halle,” among others, proved tantalizingly promising.

For us seasoned opera aficionados, we are always waiting with-bated-breath, yearning, for that once-in-a-lifetime voice to come along. With that, though, there is always caution, skepticism, and, often heart-clutching trepidation: how often have we been told we have a “new star in our midst,” complete with the requisite publicity, fanfare, and the debut recorded aria recitals accompanying all that. Only, only to have our hopes dashed within a lamentably few, short seasons? Sadly, oftener than we wish.

At that point around Davidsen’s “meteoric” splash of publicity, Perry, Ella, Doris, Frank, Nat, et al, came along and distracted me—most pleasantly so, I must add. But I digress.

When I began again with Davidsen several months ago, her YouTube output had increased quantitatively. I was able to hear her most impressive debut recital CD, but the clip that really blew me away is her account, from Prague in early 2020, of Liza’s aria of grief from Act 3 of Tchaikovsky’s Queen of Spades. At 4:35 Davidsen soars mightily, securely, in a great arc, on the sequence of notes above the staff, from A to B to A; then proceeds to take the rest of the phrase effortlessly in one breath (first time insofar I have heard *that* done):

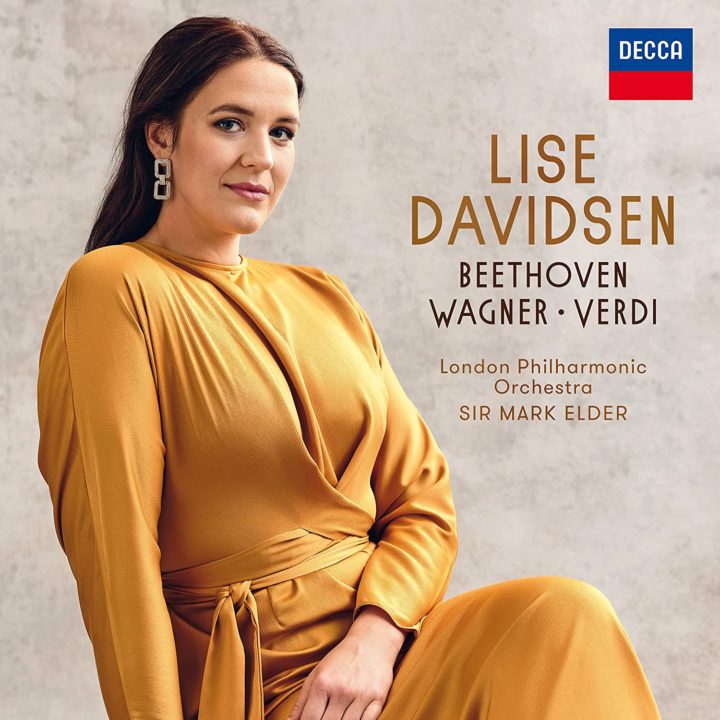

Now, too, there are a great number of interviews and mini-documentaries on Davidsen that give a rather nice overview of her as an artist. The most pronounced impression is of her wanting to serve the intents of the composer and the integrity of the music. No self-serving diva, she. This short clip with conductor Esa-Pekka Salonen has him full of warm praise of her voice and artistic dedication:As to Davidsen’s personality, character, and artistic being, this recent episode of Screaming Divas, hosted by sopranos Sondra Radvanovsky and Keri Alkema is, simply, a must-watch. It requires an hour of your time, but every second is worth it. The sagacious hostesses are wonderfully generous and sincerely gracious toward their young colleague, and the hour is not only hysterically funny and bawdy at times, but there are many crucial discussions and insights into the lives of working artists (and the pandemic’s multiple effects). Here you have what appears to be the full measure of Davidsen—smart, sincere, humble, intelligent, heartfelt, with an inborn cosmic sense of humor; most of all she possesses true charm:It is a propitious, timely and welcome event, then, to have Davidsen’s follow-up recital disc, this one featuring works by Beethoven, Cherubini, Verdi, Mascagni, and Wagner.Though the formal recorded aria recital is the ultimate calling card of an artist, the invitation to the spectator to receive, listen, and critically behold of the offerings (on fire or burnt), they are but a souvenir and there are a few drawbacks inherent with the presentation.

As we all know, what we hear on a studio-engineered recording is quite another entity from what we hear in the space of an opera house or venue concert hall. Soft-grained, flutey, non-blooming voices benefit most from studio efforts, particularly in song recitals; nuances may be captured that get diminished in a house.

Most crucially, large, resonant voices like Davidsen’s are notoriously difficult to adequately capture in the confines of a studio with a microphone just a few feet away (In the documentary The Golden Ring we see Birgit Nilsson flinging herself back from the mike in higher phrases so as not to blow the sound system to smithereens). Too, we miss out: in the house we get the full impact of the voice in its natural theatrical spaces, resonating, blooming in a multi-dimensional fashion; the studio nearly obliterates that peculiar sensation.

I asked a few trusted friends who’ve seen Davidsen live in an opera house. The verdicts all across the board were unanimous: “A class of its own,” “warmth and evenness,” “unbelievable presence and size,” and “unlike any I have heard in decades.”

Happily enough, the present recital under review gives a strong but (naturally) not ideal indication of those reactions; and one can easily hear that this is a voice of unusually outstanding quality. I hear elements of warmth of the young Kirsten Flagstad, with the occasional timbral clarity on certain vowels and notes of Nilsson, as well as some of the plush tonal shine of Gabriela Benacková.

Davidsen’s glory is in the upper middle and the top notes, which unfurl out impressively, with fullness and great security, and, most importantly, at any dynamic level. The soft tones, notably, are bright but not white or blanched. The recording reveals an occasional flutter in the more strenuous passages which I suspect might be in the house rather a vibrant shimmer; here and there in dramatic phrases the tone may issue forth ahead of, rather than on, the breath—but really, to have a voice of this caliber in our time is an unparalleled joy. Best of all, the indications are of steady, continued growth.

Yet… I had another—slight—hurdle to bypass.

Every new generation of singers have to contend with their illustrious predecessors, both in actuality and in the minds and ears of seasoned opera aficionados—and they are often a tough lot to sway. When you treasure a beloved artist’s rendition or assumption of a role, an aria, a performance held as definitive—it tends to get firmly “locked into” your aural sensibilities and registers indelibly as “ideal” to some minds. For all time, to many; the decathlon pantheon remains firmly padlocked to upstart newcomers—hostile rejection occurs if threats to those impossibly held ideals are held fast and hard. The Ghosts of Opera Legends Past permeate too many discussions, and fanatics often create antagonist artists to revile to justify their fanaticism. What a depressing prospect!

In Davidsen’s case, her staged assumption of Medea is already prompting comments on YouTube to the effect of “Sorry but this opera is just for Maria Callas.” Yet the clips in question show Davidsen to be fully up to the task, superbly committed dramatically, and vocally more than up to par of this fiendish role (we haven’t had a true contender for the part in an age and a half). The aria “Dei tuoi figli la madre” in this recital reveals the soprano immersed in the drama of Medea’s mad musings with its outbursts of forlorn melancholy interspersed with desperate hysteria, while still hewing to the Classical nature of Cherubini’s line, coping well with the sudden vaults into the upper register. It’s an exciting, vivid performance.

Not that, mind you, I am free of my own set-in-my-ways biases. I have held Fiorenza Cossotto’s Santuzza, indeed the aria “Voi lo sapete” from the classic von Karajan complete recording of Cavalleria Rusticana as nonpareil for decades now. I held prissily onto my memorized reason why when I first heard Davidsen’s rendition. So what do I do—I pull out my score and consult that rather than Cossotto and listen carefully while following along. And repeat, and repeat. FloCo placed respectfully aside for now.

I was quite surprised to learn that Davidsen has already sung Santuzza onstage; it didn’t seem, in my conditioned mindset, that verismo would figure in her career or vocal disposition—this is the lady with the promising future in Wagner, you see.

But Davidsen persuaded me—fully—otherwise in her performance of this, the most famous and well-trod of all the operatic warhorses. She begins the aria with quiet, mournful urgency, and as she increases the narrative, growing more agitated; the soprano does “l’amai,” in one breath into the “Ah!” on a high A, marked with ff, with the instruction con grande passione—and still on the same breath, the repeat of “l’amai.” Davidsen soars thrillingly, not only with the power of her tone, but it imparts the high-voltage dramatic effect. Incidentally, the Italian here and in the other like selections is excellent and idiomatic. Lovely is the tearful “Priva dell’onor mio,” as is the repeat of “Io piango,” broad and tragic in its declamation. The two “Io son dannata”s are well contrasted; and particularly exquisite is the dolcissimo G# on “supplicarlo.” So Davidsen doesn’t have the pungent, chesty low notes of the typical Italian soprano of old, but so what; this is a legitimate Santuzza, and they are hard to find now.

The “Pace, pace mio dio” is simply splendid: long-lined, expressive, expansive, eloquent, deeply felt. The two B flats—the first marked pp,the second not marked (Ricordi here) but organic sense, from the orchestral tutti, indicates it must be fff—are both done to their fullest values: the initial one a genuine pianissimo, shining and gorgeous. The capping one caused my jaw to drop: it is hair-raisingly resplendent, torrential, and magnificent:

One of the pitfalls of being a discriminating opera aficionado and a self-appointed critic is that I tend to focus so much on the intellectual and the technical that I can (dumbly) forget to react emotionally. Davidsen in her reading of Desdemona’s “Ave Maria” caught me shedding tears. It is sung with great poise, poignance, and ravishing beauty, with exquisite portamenti (as on “Gesù”), and the softest of shining tones. The phonation of the vowels are clear, the text imbued with graceful shadings.Of the two Beethovens—Leonore’s great scena “Abscheulicher!” from Fidelio and the splendid concert aria “Ah! perfido”—the latter I think is just a mite more suited to Davidsen now than the former: the tessitura is slightly lower, and I have a hunch that as the voice matures, the womanly ideal for the devoted wife in the Mittellage will materialize in time. It is already a much-heralded, acclaimed assumption; her best Leonores are yet to come, affirmatively.

The concert scene, in three sections, is done with masterful skill. The recitative, which has over a half-dozen mood shift tempos by Beethoven indicating the rapid acceleration of conflicting emotions, has Davidsen intensely expressive, particularly in the “Va, scellerato!,” in which she uses a hollow, scalding tone of hate; and moments later, warm and imploring in the closing phrases from “Risparmiate quel cor, ferite il mia!”

The aria “Per pietà, non addio,” a deeply felt adagio, shows Davidsen in her affinity for the slender, elegiac line and suave handling of the slow figurations; she has an ability to depict the effect of mournful sorrow without becoming lachrymose. The concluding section, “Ah crudel! tu vuoi ch’io morra!,” set to an allegro assai, the soprano displays her remarkable agility, with clean scale work free of aspiration and clunkiness; dazzling are her breathtaking vaults to the upper register. This is a finished and thoroughly satisfying performance, musically and dramatically.

The five Wagner Wesendonck lieder, set to orchestra, are the pieces with which I am least familiar. They sure do feel Isoldean in musical scope and in their sensibility. All of them are consummately sung, and feel like they were written for Davidsen. I think it best to here present the video featuring the third song “Im Treibhaus” from the actual recording session; reason being to take in the soprano and her complete immersion into the music and narrative—she’s a joy to watch as well as to hear:

Rounding out the proceedings are Sir Mark Elder and his exemplary London Philharmonic forces; all the styles of the different composers are handled with conscientious flair, and there appears to be a strong collaborative sense between conductor and soloist. The whole endeavor is permeated by a feeling of an auspicious occasion event.Now may we have in not too long a time a new Tristan und Isolde recording with Jonas Kaufmann and Davidsen?