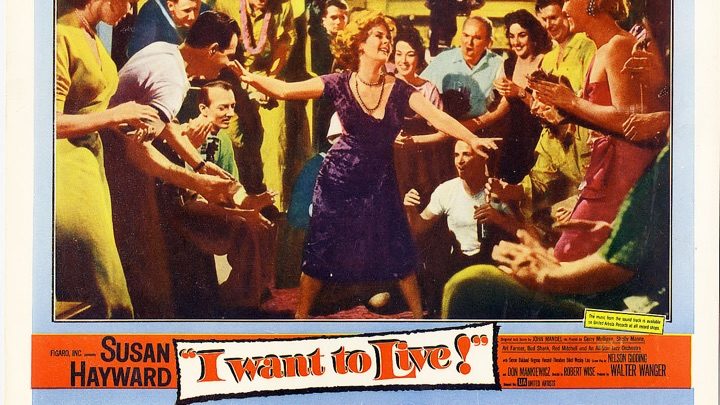

David Fox: The tonal shifts here are enormous, and they start from the very beginning. As you say, a quote from no less than Albert Camus (he had won the Nobel Prize in 1957, one year before this movie)… followed moments later by the production company, Figaro Film, cute cartoon insignia, accompanied by some cheerful piano riffing on the Mozart overture. No sooner is that finished than we move into one of the truly great jazz film scores, composed by Johnny Mandel with a group of legendary musicians including Gerry Mulligan and Shelly Mann (both of whom make cameo appearances) and a visual world full of noir edginess. The setting is a nightclub, and we know it’s hip because everything is shot at an angle. It’s a lot to take in… and we haven’t even gotten to Susan Hayward yet! I have to say I struggle with I Want to Live! The camp appeal of it—including Hayward’s performance—is undeniable… yet it’s also a sincere and even important movie. Watching it this time, I realized that the Rosenberg execution had happened only five years earlier. It’s often an awkward movie, but sometimes a major one. Much the same could be said of Hayward’s Oscar-winning performance.

CK: I think it’s worth remembering that a lot of “message” films of this era came wrapped up in a brash insouciance that, as you say, reads to us as camp. That’s definitely the case here. But I also think that’s a lot of what makes the movie so engrossing—it walks right up to the line of good taste at some moments, steers into self-righteous territory at others, but, most importantly, avoids weepy sentimentality. And Hayward is the perfect star for this kind of vehicle. Her character, Barbara Graham, is no angel; she doesn’t go to the gas chamber trailing a halo. Yet it’s her troubled life and faulty attempts at redemption that ultimately make her a sympathetic, human protagonist. Hayward is great at playing her vulgar side, but while no one would ever call her brand of acting subtle, she also locates the pathos without overdoing it. It’s a rich, layered performance.

DF: You began by mentioning Hayward alongside Barbara Stanwyck, and I want to pursue that a bit, because the comparison is revealing. There are some similarities in their images—both Brooklyn girls who became major stars but never entirely ditched the image of their hard-scrabble backgrounds, and both gave some of their best performances by trafficking in toughness. But Stanwyck is often so understated as to seem to be doing almost nothing. (Of course, that’s part of her genius.) No one will ever accuse Hayward of understatement, and maybe least of all here. Her opening moment finds her in silhouette on a bed, tossing her head back as only Susan Hayward can. From the start, she’s defiant, brazen, and bigger than life. A key gesture comes a bit later: when asked if she’s willing to deal, she shakes an empty hand, opens it for the reveal, and announces, with fire in her eyes, “no dice!” (A group of my friends and I still imitate this from time to time!) Hayward’s Barbara Graham smokes so much I wondered how she managed not to die of lung cancer long before she went to the gas chamber. But there’s power and even brilliance in her bigness.

CK: If you’ll forgive the expression, the stakes of this story are pretty high, and Hayward’s performance rises to meet them. I would push back on any assertion that her outsize persona suggests a deficit of talent. On the contrary, it often seems clear that Barbara’s bravado is her defense mechanism, and in well-selected moments, she reveals the pain she’s had to survive, which has turned her into the tough dame who meets her faith with a fair amount of steely reserve. Consider how she recounts her unfortunate upbringing in an early scene, or how the hopes for a reformative marriage and a chance at suburban tranquility so quickly fade away. Or watch Hayward in the jailhouse scene where Graham’s toddler son is brought for a visit, only to have the private moment between mother and child turned into a photo op for the press. Hayward, like many great actors, always seems to be operating on several levels—public and private, brash and vulnerable, violent and tender. It’s no surprise she was a favorite of the Cahiers du cinema critics who ultimately ushered in the French New Wave… her style would not be so out of place in something directed by Godard or Truffaut.

DF: The French connection (sorry) reminds us again of the high-mindedness of I Want to Live!, which brings me back to the awkwardness of my feelings about it. The movie’s solemnity and sincerity certainly test the limits of camp—to me, this pretty much defines the “guilt”of a guilty pleasure—yet it’s hard not to revel in the combination. What gay audience member seeing it now will not perceive that Graham’s apprehension by the police, which is preceded by a quick comb-through to make her hair look presentable, is the Urtext for Helen Lawson’s bathroom exit in Valley of the Dolls? But at the other extreme, who could be immune to the stomach-churning horror of the movie’s unflinching final 10 minutes, in which the execution is shown with virtually no cutaways?

CK: You sort of just have to take the film on its terms—it’s melodrama, true crime, women’s picture and realist manifesto, occasionally all at once, and often as thrilling as it is jarring in tonal variety. It’s also a really great chronicle of character acting in the period, with a solid supporting cast of mostly B-players who bring a lot of spice to the smaller, more archetypal roles.

DF: I’ll say! While I Want to Live! is first, last and always Miss Hayward’s movie, the supporting team is a truly dazzling array of you-may-not-know-the-name-but-you-certainly-know-the-face actors, including Stafford Repp, John Marley, Simon Oakland, Gavin MacLeod, Alice Backes, and of course, Theodore Bikel. (What I wouldn’t give to be a fly on the wall listening to Hayward—a staunch Republican—and Bikel—a legendary liberal—debating the death penalty!) If these aren’t reasons enough to see the movie, there’s also Lionel Linden’s magnificently gritty black-and-white cinematography, which evokes California in 1950s as well as I’ve ever seen on film.

CK: I Want to Live! won Hayward the Oscar for Best Actress on her fifth try. Next, we’re going to look at two of her other nominated performances, ones that share a common theme—Smash-Up, the Story of a Woman and I’ll Cry Tomorrow, which find our heroine crawling deep inside a bottle. Bottoms up!

Comments