La Cieca: To begin, the “boxers or briefs” question”—Boston or Stockholm, and why?

David Alden: As seductive as the idea of directing a Verdi opera about Colonial Boston feels (Ulrica the outlawed black fortune-teller, the clash between the effete British ruler Richard, Earl of Warwick and his American subjects, Renato his “Creole” secretary etc.) let’s face it—this American location was chosen almost at random by Verdi to deal with the Italian censor’s banning the depiction of the assasination of a European royal figure. The sound of the musical score is the always the decisive factor in an opera, and Verdi’s score is 100% sparkling European in flavour—the court of Gustavo is a mini-Versailles, elegant and full of sophisticated intrigue—Auber’s Le bal masqué was the previous famous opera on the historical subject of the assassination of Gustavus at Drottningholm and Verdi’s score takes Auber’s French flavour as an inspiration. So Sweden it must be—but our production will not be a historical re-creation of the late eighteenth-century Swedish court. Rather, the cool and repressed Nordic environment (echoes of Bergman and Strindberg) will be evoked.

LC: The Met’s PR materials describe your approach to Ballo as “dreamlike.” Can you expand on that? What about this work (as opposed to, say, Aïda or Trovatore) suggests a dreamlike approach?

DA: I think this is Verdi’s brilliant and despairing existential riff on human existence—his Gustavo is a dreamer and a fantasist—a king who wants to escape his duties, who initiates an affair with the wife of his staunchest defender almost to create his own assassin (Christ and Judas?)—a king who laughingly (how many kinds of laughter there are in this piece, ranging from light to diabolical to desperate) plots his own death step by step. Of course all operas are dreams (the tension and synergy between words, which are rational and precise, and music, which is subjective and mysterious). But Ballo (along with Boccanegra) are the two clearly experimental dream pieces in Verdi’s output.

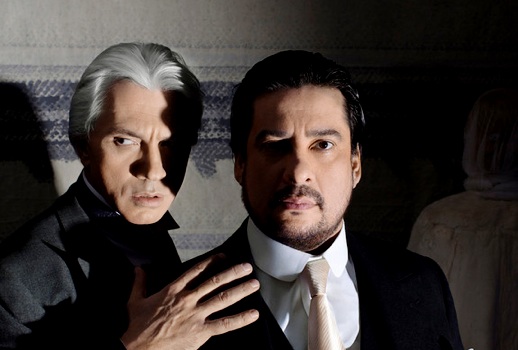

LC: Your cast for Ballo includes Dmitri Hvorostovsky, who’s well known as a singing actor, and Marcelo Alvarez, who is best known as a “singer”. Is there a different approach in working with artists who have a native flair for acting and those who don’t so much?

DA: I am excited to meet this starry cast—I have never worked with any of them before (actually I worked with Dolora Zajick once decades ago in San Francisco when she was beginning in the Merola program but it was several lifetimes ago). Of course I have seen them all perform countless times around the globe. In rehearsal I try to create an atmosphere of collaboration, discussion and experiment—I am very well-prepared and sure of where I am going (usually) but with such a cast I hope I can throw all my notes away, improvise, and take as much from them as I put in. You would be surprised how often I work with a singer who has a reputation for being stubborn or not an actor and draw them into my world and get something fluid, intense, or unexpected—this I consider my job. These people are thoroughbreds who can function on a very high level! but you have to be at the top of your game and a step or two ahead of them.

LC: A corollary of sorts: when you signed on to this production, Karita Mattila was Amelia; now the role has been passed on to Sondra Radvanovsky. How will this major change of cast affect your approach to the work? Do you think the production will vary from your original conception to fit her personality, or do you expect her to fit into the concept?

DA: Of course Sondra is completely different from Karita and the production will be very different with her as Amelia—we have already adjusted the costume designs for her and I will enter rehearsals open and ready to change everything based on her energy, her voice, her physicality. If Kim Novak had pulled out of Vertigo and, I don’t know… Vivien Leigh had played the part, it would be a very different film.

LC: A general question about the work: to me it feels different in so many ways from what we think of as stereotypically Verdi. Can you comment on what makes Ballo unusual or unique among Verdi’s oeuvre?

DA: This opera is unlike any other Verdi creation—the bizarre combination of serious political material, high Italian melodrama based around the hackneyed stuff of marital infidelity, and an almost operetta-like lightness of being, is experimental and dislocated and sets this apart from his other masterpieces.

Ballo Photo: Brigitte Lacombe/Metropolitan Opera.

Comments