I’m not sure who I find more annoying – the partisans who vigorously defend Luc Bondy‘s production of Tosca at the Met or those who decry it. As Bondy’s production replaces one of the Met’s signature offerings, both groups have seized on this event as a watershed event in the history of opera in America and have been flogging their opinions of the production endlessly so as to advance their broader agenda. So once again, poor Floria Tosca has become a victim in a war that she wanted nothing to do with.

Let’s start with the pro-Bondy faction. For them the booing of the production represents the latest and most egregious example of American cultural provincialism. We’re nothing but a bunch of small-minded yokels who judge any opera production by how much we like the scenery and costumes.

In America, opera is a Las Vegas floor show with better music and the boobs sitting in the expensive seats. They imagine the Met’s audience to be composed entirely of literalist Antonin Scalias who don’t see any penumbras of interpretive possibility within the standard repertoire. In other words, anyone who dares to dislike the Bondy Tosca is a close-minded moron.

Conveniently, this leaves no room in which to criticize Bondy’s work. Sure, Luc Bondy is a justly famous director who was long overdue for an engagement at the Metropolitan Opera. Still, the audience is not there to pass judgment on Bondy’s résumé; they are there to see Tosca. And he gave the Met a Tosca that was dead long before the heroine made her final non-leap.

Part of what makes Tosca such compelling theater is that all the lust, betrayals, and depravity unfold in dazzling, famous settings and the tension between venue and action adds a special edge to the drama. If the typical James Bond film unfolded in council flats and office cubicles, there would not be much a 007 franchise.

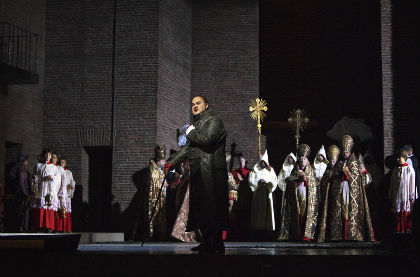

Yet Act I of Bondy’s Tosca takes place in what looks like whatever is the catholic analogue to a rehearsal studio; Baron Scarpia conducts his campaign of torture and seduction in a room that robbed him of his taste and elegance that make his evil that much more shocking; Act III dispensed with the skyline of Rome looming large in the distance as well as Puccini’s carefully orchestrated dawn and put us down on the riverbank for no particular reason (why didn’t Tosca swim away?).

What did this achieve for the drama? Nothing at all. And Scarpia’s rug really made my eyes hurt. There were numerous other directorial interventions in the long slog to the finish and none of them brought the audience any closer to Tosca.

Somehow I’ve become a philistine just because I didn’t like the production. That, to me, is the essence of philistinism – making snap judgments without probing or questioning. I’m amazed at how many Bondyphiles have decried the stupidity of American opera audiences without even having even seen the production in question. And no, the HD broadcast does not count as experiencing the production any more than reading National Geographic qualifies as traveling.

American audiences are actually open to a broader range of approaches to the standard operatic repertoire than the Bondy-philes would give us credit for. Herbert Wernicke’s Die Frau Ohne Schatten was warmly applauded at its premiere, even though it represented a significant departure from the previous iconic production.

Met audiences have even come to see the virtues of the Robert Wilson Lohengrin, despite the controversy at its premiere, where the booers and the cheerers each tried to drown each other out. A second viewing and a different cast better capable of responding to the unique physical demands of that production made all the difference.

I doubt, however, that Bondy’s Tosca will find its public at the Met as the Lohengrin did. And frankly, given Bondy’s condescending remarks about American opera audiences, it doesn’t deserve another chance. Why the heck did he bother to accept the engagement of directing Tosca here if he knew the audience wasn’t going to appreciate his work? Did he need the money that badly or did he feel compelled to cross Tosca off his to-do list? It couldn’t have been satisfying for him and sadly, it wasn’t satisfying for the audience either.

The decriers are just as insufferable. As they see it, the greatest threat to modern culture is director-driven opera production. The Sybil Harrington era Met productions are a precious endangered species that must be protected from the killing machine of the regie-industrial complex.

The problem is that the Zeffirelli Tosca is an awfully shaky piece of ground for the operatic Éponines to build their barricades on. That Tosca was never his best achievement; that would probably be the Otello. Sure the set designs were impressive in their realer than real evocation of the locations specified in the libretto, but the director seemed to focus most of his energy on drawing oohs and aahs from the audience at the expense of creating much actual drama.

The big coup de theatre was to have the action in Act III shift between the roof of the Castel Sant’Angelo to Cavaradossi’s cell below by means of the Met’s stage elevators. Never mind that it distracted from a carefully planned introspective moment in the music, it was fabulous. In this production, Liberace’s candelabra would have fit in just fine flanking the deceased Scarpia.

Otherwise, the director did not manage to elicit particularly convincing acting from his principals (even by the standards of other performances they gave at the Met) and Tosca was burdened with a Procrustean pink prom dress that no diva could ever fit comfortably into. Despite its supporters assertions, little about this Tosca could be considered “definitive.”

Moreover, Zeffirelli only directed this production in its first season. Assistant directors took over starting in the second season, and as in the game of telephone, what transpired on stage in subsequent performances bore less and less resemblance to whatever Zeffirelli intended. The Met has only seen performances of the “Zeffirelli production of Tosca” during one season. That production was replaced years ago by performances using the Zeffirelli scenery and whatever business and dramatic ideas that year’s protagonists brought with them.

Good opera aspires to be more than that. Puccini chose Tosca as the subject for an opera because of a performance he saw of the work in the theater. He wanted to capture the essence of the drama he saw on stage; not mollify his audience with pretty music and pretty scenery.

A good director can bring us closer to realizing what Puccini desired and we shouldn’t settle for the Zeffirelli Tosca simply because it doesn’t challenge the received wisdom of what a traditional Tosca should look like. In its own way it’s just as half baked as the Bondy one – overdone on the outside; undercooked on the inside. And the Met deserves a better Tosca than either producer was able to give us. I can only hope that we don’t have to wait 25 years for the next one.