Instead, we’re honoring him from a distance, as we (and likely he) sit at home, in quarantine.

At least the time away provides an opportunity to ponder, with waves of nostalgic pleasure, how the Company original cast album gave 14-year-old me—then living in the quiet but dull comfort of suburban Southern California—something to aspire to.

I can still remember riding my bike to the local record store, thrilled to find the just-released LP in stock. If I recall correctly, I shelled out $3.99 plus tax, put my newly acquired treasure in my bike basket, and rode home to listen.

Of course, I already knew a bit about the show, which had been trumpeted by many critics as an innovative and rule-breaking new work that spoke to the next generation of musical theater lovers. Well, I thought, that’s me—I must explore Company myself!

Actual evidence, though, was in short supply. I read reviews, of course. But I found it difficult to conceptualize the non-linear plot format, episodic nature of the storytelling, and the sophisticated relationships that were often mentioned. Even the show’s famous poster, which I’d seen rendered in several places, seemed slyly obfuscatory, giving virtually no sense of the show. (As I often suggest to students when I teach it now, the only information provided is arguably incorrect: whatever Company may be, it’s not a “musical comedy.”)

As for that music—again, reviews were enticing but maddeningly opaque.

It would be a while till I could see the show for myself. Actually, I can tell you exactly when: May 20, 1971. That was Company’s premiere in Los Angeles; by sheer luck, it was also the day after my fifteenth birthday. As a gift, my parents took me and a friend to the opening.

By then, I had a better idea what to expect from the recording… and what a mind-blowing experience that was!

To start at the beginning, there was the structurally free-form and fantastically original opening number, regularly interrupted by everyday noises, ranging from conversational insertions to a telephone busy signal. Sondheim’s sound-world was bewitching but also perplexing. Often it seemed surprisingly like contemporary pop. Now, with a more practiced ear, I can hear specific traces of Burt Bacharach and Herb Alpert’s Tijuana Brass, in particular.

But there was also that thrillingly unmistakable sound of “theater” in the score, and the lyrics—those that I could actually comprehend with my 14-year-old brain—were astonishingly witty and insightful.

Favorite songs at the time: “You Could Drive a Person Crazy,” with its snazzy 1940s bounce. I congratulated myself for recognizing the Andrews Sisters’ style from records , though I didn’t then—and frankly, still don’t—quite understand the pastiche. “Another Hundred People” was near the top of the list, for sure. (Hearing the great Pamela Myers’ sing this in person—in 1971, and maybe even better in 1993—remain indelible theater memories.)

Also, “Getting Married Today”, though trying as hard as I could at home, I never managed the long lyric lines without extraneous breaths. I shouldn’t even get started on “The Ladies Who Lunch,” or we’ll be here all night. Suffice it to say that because of this song, I knew how to mix a vodka stinger long before I could legally drink one.

And of course, “Being Alive,” which would grow to mean so much more to me in the decades following the show.

Indeed, I doubt a month has gone by when I didn’t dip into the Company original cast recording—if only to hear a song or two and be whisked back in time to that magical moment I discovered the show.

I’m not alone, of course. Clearly this show, and the album, meant a lot to a lot of people.

How else to explain Original Cast Album, the likely unprecedented D. A. Pennebaker documentary about the Company recording sessions, which in just under an hour give priceless if frustratingly incomplete hints of what that amazing original cast delivered on-stage?

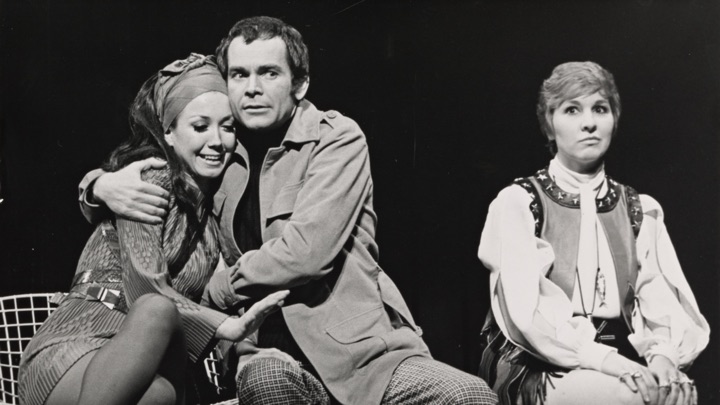

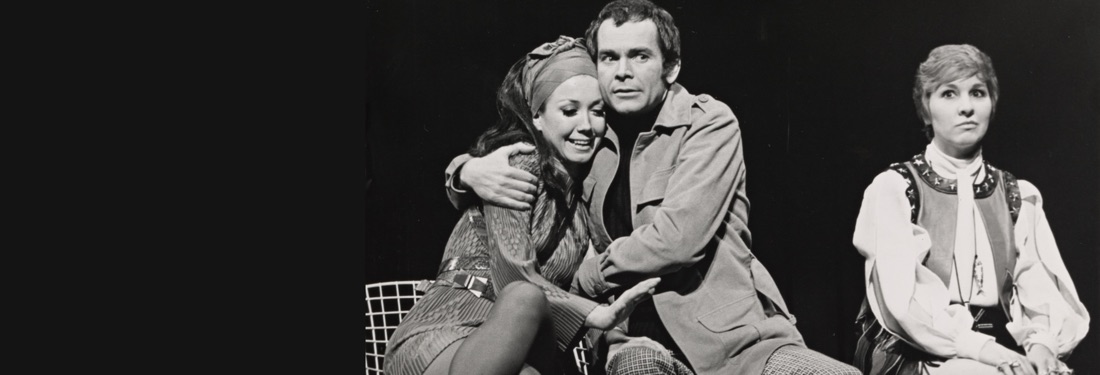

The film is especially valuable for glimpses of Dean Jones as Bobby—Jones famously dropped out of the show early on, leaving behind the ghost of what many recall as a performance never since equaled.

Even more famous, of course, is Pennebaker’s unflinching account of Elaine Stritch in full meltdown while recording “The Ladies Who Lunch”… only to (what else) rise, rise, rise!… to the challenge, one day later. I think of it as a tiny simulacrum of The Full Stritch: Tragedy to Triumph, and I know at least a half-dozen gay men (myself included) who can enact this entire episode off-book at least as well as she does.

The Stritch episode in particular is parodied to perfection by Paula Pell in the hilarious send up mockumentary, Co-op: The Musical, which—scene-by-scene—naughtily recreates Pennebaker’s documentary. For those keeping count at home and attempting to figure out how many variations there are on this theme: Co-op is a riff on Original Cast Album… which, of course, would not exist without Company itself.

That’s how famous and important this show is—three degrees (and counting) of satire. Co-op is the inspired brainchild of John Mulaney (who appears here as a barely disguised doppelganger for Sondheim) and Seth Meyers.

All this history, and I haven’t even begin to touch on the many revivals of Company. Still more unusual are the multiple ways this 1970 show has been rethought and tweaked—including by Sondheim himself—in the half-century since it debuted and forever changed the way we think of musical theater.

Marianne Elliott’s London production is, by most accounts, the most radical of all. Sadly, it’s now unclear when American audiences will have a chance to judge if for ourselves. (Had things worked out differently, Cameron Kelsall and I would be reviewing it here in parterre box today, instead of my writing this column.)

I certainly look forward to that day, though I also don’t mind stating my own preference for contemporary productions of Company that preserve the original show as period piece: an extraordinary time capsule of Manhattan at the end of the 1960s, immersed in a rapidly changing world of what it meant to have and sustain a romantic partnership.

How I wish we were all celebrating in person today in public, with Mr. Sondheim in our midst! Alas, that must be postponed. Instead, let’s all look forward to this next year. After all, 91 is the new 90.

Till then, a very happy birthday to Stephen Sondheim, who has unalterably changed our theater for the better. And my own life, too.

I’ll drink to that!

Comments