In the comments on a recent “Change my mind about…” item about the happy ending of Gluck’s Orpheus opera, more than one reader admitted to not seeing what is so great about “Che farò senza Euridice?” It takes courage to confess to not getting something that has been held up as a masterpiece for over two hundred and fifty years, but those brave souls are not alone. Even in Gluck’s day, the music was criticized for an emotional restraint that borders on detachment. Gluck himself admitted that “nothing but a change in the mode of expression is needed to turn my aria ‘Che farò senza Euridice?’ into a dance for marionettes.”

That problem is compounded for present day listeners as the aria exists in four versions for three different voices in two languages. Most of us first encountered the aria in the version farthest removed from what Gluck wrote.

Orfeo ed Euridice was first given in 1762, in Vienna, as part of the name day celebrations for Francis of Lorraine (the stay-at-home husband of Empress Maria-Theresa), written in Italian and with Gaetano Guadagni, a contralto castrato, as Orfeo. It was Gluck’s first “reform opera” in which he set out to create a new synthesis of words and music, eschewing vocal display, and formal repetition that did not support the text or further the action, and aiming for more direct communication and emotional truth. Response was more approving than enthusiastic.

Gluck was also music teacher to Marie-Antoinette, the Empress’s youngest daughter, who must have been present at the premiere of Orfeo. With her support, in 1774, Gluck was invited to Paris with a contract to present Orphée et Eurydice as one of six new operas. In addition to a new French libretto, the opera was adapted to appeal to French taste. New dance episodes were added, the role of the chorus was enhanced, the orchestration was simplified, and the lead roles were expanded. Most significantly, because the French preferred their operatic heroes anatomically intact, the role of Orphée was rewritten for a high tenor (haute-contre), giving him a more masculine, virile, “heroic” sound. Some of these changes were a step back from Gluck’s reform ideals, but they were shrewd decisions. The French version was a huge success. “Che farò senza Euridice?” became “J’ai perdu mon Eurydice” and while the changes to it do not appear very great at first glance, they are significant.

Pauline Viardot as Orpheus

The success of Orphée et Eurydice was such that its popularity survived the French Revolution, the Napoleonic era, and the vicissitudes of French social and political life following the Bourbon Restoration, but it’s place in the repertory was threatened by changes in tuning. Over the first half of the 19th century, French concert pitch rose steadily to the point where no tenor could sing Orphée without so many transpositions that performance became impractical. The solution was for women to take on the role. In 1854, Liszt made a version for contralto with a new overture of his own, and Meyerbeer suggested to Pauline Viardot that she get someone (but not him) to make one for her. That someone turned out to be Berlioz, a Gluck devotee with a thorough knowledge of both the French and Italian versions. Berlioz stuck closely to the 1774 score but reverted to the original orchestration where he considered it superior.

The Berlioz version provided a singable score, but it presented its own challenges: it contained more dance than many opera companies could manage and made great demands on the chorus. It was also in French at a time when opera – if not in the local language – was in Italian. (The Metropolitan Opera opened its doors, in 1883, with Faust in Italian.) In 1889, Ricordi published an edition that was more expedient than scholarly. It was based on the Berlioz but with the Italian text, returning to the Italian score where the words did not fit the French music, and cutting some of the Paris choral and dance music. At the same time, some of the Paris additions that did not exist in the original, but were flattering to singers, were retro-translated into Italian. Singers and conductors cut and added at will. Toscanini and Louise Homer interpolated “Divinité du Styxe” (from Alceste) at the Met in 1911. And it was the Ricordi version in which Orfeo ed Euridice became established (until quite recently) as the oldest opera in the standard repertory and was the version in which I first saw the opera at Santa Fe in 1990, with Marilyn Horne and Benita Valente.

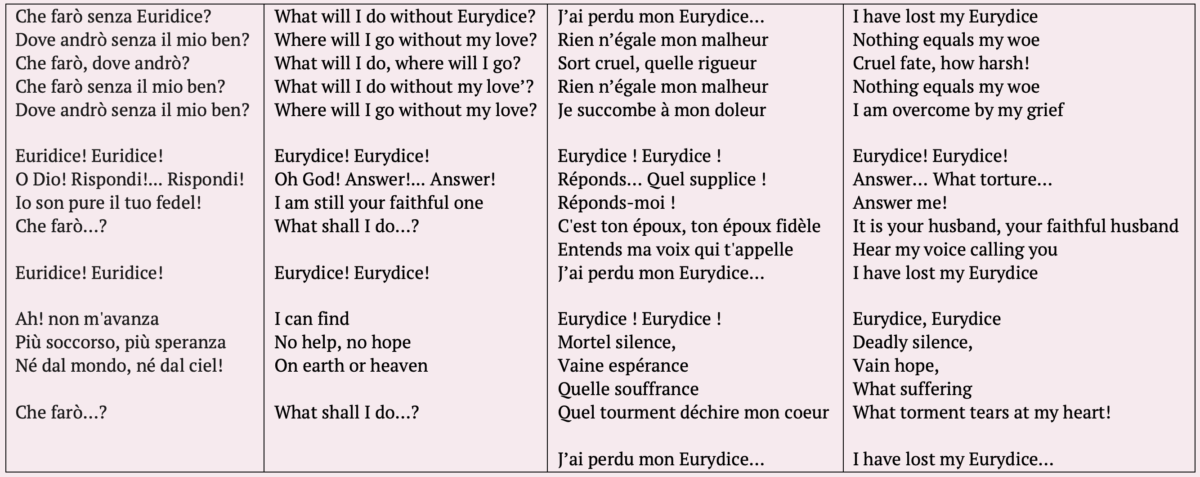

Whatever the version and whether one sees the action in literal terms or as a metaphor for the stages of grief (or any other interpretation), this aria is the climax of the opera: the moment when Orpheus faces the terrible permanence of loss. How he does so, however, is different in Italian and French. One doesn’t need to know a word of either language to see that “Che farò senza Euridice?” is a question, whereas “J’ai Perdu mon Eurydice” is a declarative statement. One is an active thought process, the other a formal lament.

In both versions, the aria’s structure is in the most basic rondo form: ABACA. The simple, music box refrain contrasts with the emotionally loaded episodes. In a sensitive performance, that contrast is what creates the aria’s impact. Musically, the only differences are the key (F for the Vienna and Berlioz versions, C for 1774) and a small but important change at the end. (We’ll get to that.)

When the Met first staged Orfeo (1891) one admiring critic found “Gluck’s grand simplicity restful,” and praised his “pure, chaste music.” At a time when La traviata and Don Giovanni were regularly condemned for their indecency, Orfeo was utterly respectable, an opera to which one could take one’s marriageable daughter. This decorous, respectable chastity became the norm for many a great singer. Gluck instructed Guadagni to sing his cries of ‘Euridice!’ in the first scene as though his leg were being amputated, but performances like this by Maureen Forrester – matronly, metronomic, with all the urgency and intensity of a Methodist hymn — were standard for most of the 20th century and do little to dispel the impression that, as Peter Schaffer wrote in Amadeus, Gluck’s characters are “so lofty they sound like they shit marble.”

But Forrester is singing Italian words to French music, written for a man. Scraping off the top layer of traditional accretions, and working backward toward Gluck’s original, Maria Callas’s recording of the Berlioz-Viardot version gives us the French text with the French music. It may not be what Gluck wrote, but the balance of classical restraint and deep pathos is hardly restful. Whether it is Callas’s superb instincts as an actress or the product of research, she not only contrasts the episodes with the refrain, but varies the refrain each time it returns in a way that recalls accounts of Viardot’s own performance.

In 1859, the year Viardot first sang Orphée, a government decree standardized French pitch at A=435, making it possible for tenors to resume singing Orphée. However, the haute-contre, style, which blended chest and head voice (or falsetto) for higher notes, was giving way to a new breed of tenors who sang high notes with full chest voice and Orphée remained a women’s role. In the mid-20the century, men – notably Léopold Simoneau, Nicolai Gedda ,and, more recently, Juan Diego Flórez — started singing it again. Whether they are genuine haute-contre or not I will leave to others more knowledgeable that myself. Simonau’s performance (available on YouTube) it is a classic. This example, however, is by Richard Croft, from a complete recording of the 1774 version.

I was amazed the first time I heard Orphée, a young man in despair, sound so much like… well, a young man in despair. After the Paris premiere, the influential salonnière Mlle Lespinasse wrote, “this music drives me mad; it carries me away […] my soul is eager for this kind of pain.” By coincidence, 1774 was also the year Goethe published The Sorrows of Young Werther, another story of a young man in despair that caused a similar sensation. Gluck and Goethe had tapped into a growing dissatisfaction with the rational optimism of the Enlightenment. Gluck was ambivalent about giving his opera a happy ending. Convention demanded it, but people needed a good cry.

By the time Gluck adapted the opera for Paris, he had realized that too much reform at one time was not conducive to commercial success. He gave Orphée a bravura aria in the first act, and, with the addition of just two measures that delay the final cadence, turned “J’ai perdu mon Eurydice” into the prototypical eleven o’clock number. Those two measures, repeating the last words (“à ma douleur”) fortissimo, on sustained high notes, make for a boffo ending. Of course it moves the gods to pity, and the happy ending feels almost inevitable. Without that kind of climax, “Che farò senza Euridice?” is an introverted moment, a brutally real portrait of suicidal ideation, making the subsequent ex machina happy ending all the more discordant. Perhaps that’s what Gluck wanted.

Orfeo ed Euridice is a far more radical work that Orphée et Eurydice. The Vienna Orfeo is not especially heroic. The Furies call him a “misero Giovine” (wretched boy) and pointedly remind him that he is no Hercules. The sound of a male treble comes closer to that kind of vulnerability. Orphée, the great bard, eloquently describes his grief to the universe. Orfeo, the wretched boy, singing only to himself and his dead wife, experiences his grief in real time. “What shall I do, where shall I go?”is not a rhetorical question to which Orpheus continuously returns. It is real and the only answers are terifying. Any fewer words and he would be inarticulate. The simple melody and rondo form make perfect sense for the situation and the character. In this context, and considering Gluck’s feelings about vocal display, the singer must be very careful about where and how to ornament; the question must not lose any of its stark terror to pretty detail. Compare the following clips: both are very fine performances, but David Daniels emphasizes the words “where?” and “what?” with abrupt, disconcerting leaps, whereas Jakub Józef Orliński seems to ornament because that’s what one does in18th century music. (Warning: the camera work and emoting are such that you may want to listen without watching.)

A countertenor is not a castrato and questions remain, too, about the true haute-contre sound. So we are left with two equally “authentic” arias, neither of which is going to be performed exactly as Gluck imagined, but both of which have their place. Onstage, the Vienna version is the better opera. Its brevity, its unbroken focus on Orfeo, and its stark simplicity give it the potential to be devastating, happy ending notwithstanding. The Paris Orphée, however, contains much beautiful music (the extended Dance of the Blessed Spirits, “Cette assile aimaible et tranquille,” etc.) that I would not want to be without and which I am glad to hear on recordings. And I don’t think there’s much question that in isolation – on record on in concert – “J’ai perdu mon Eurydice” is the better aria, regardless of the sex or vocal range of the singer. So, I’ll end with that one, sung by Michael Spyres, the finest helden-haute-contre-baritenor before the public today.