Monika Rittershaus

“Where you come from, you will not be missed; where you are going, you will not be welcomed.”

The year was 1941. A repurposed cargo ship – the Capitaine Paul-Lemarle – left Marseille bound for Martinique (in the eastern Caribbean), bringing several hundreds of refugees fleeing Nazi-occupied France. Numerous prominent artists and intellectuals were present among those passengers, including André Breton (poet and leader of the Surrealism movement) and his second wife Jacqueline Lamba, Afro-Cuban painter Wilfredo Lam, social anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss, Russian Communist writer and historian Victor Serge, and German-Jewish writer Anna Seghers (who warned of the Nazi dangers in her 1932 novel Die Gefährten).

That is not a description for an episode of the 2023 Netflix miniseries Transatlantic, which also depicted such an event. It is the starting point for William Kentridge’s new theatrical project, The Great Yes, The Great No, which received the Bay Area premiere at Zellerbach Hall on Friday, March 14. Returning to Cal Performances after his successful residency in the 2022-23 Season culminated in the triumphant U.S. premiere of Sybil, Kentridge’s ambitious new work is the anchor for Cal Performances’ Illuminations theme for this season, specifically titled “Fractured History” and aiming to “unite the power of the performing arts with UC Berkeley scholarship to dive into what we truly know of our past, and how that understanding shapes our present and future.”

In The Great Yes, The Great No, Kentridge expanded the passenger list with several famous figures from the past and future, morphing the very real event into a mythical realm. First came the founders of the Négritude movement in Paris, including Jeanne “Jane” and Paulette Nardal, Martinican writers Aimé and Suzanne Césaire, Senegalese writer Léopold Sédar Senghor, and French Guianese poet Léon-Gontran Damas. Philosopher Frantz Fanon jumped back in time to join the journey. Also on board were Joséphine Bonaparte(another Martiniquais), Josephine Baker, Leon Trotsky, and for a short while, even Joseph Stalin! Not satisfied with that list, Kentridge conceived the ship’s Captain as an incarnation of Charon, the ferryman of the Underworld on the River Styx, adding another layer of symbolism to the proceedings.

Kentridge described his approach in the program notes:

“The journey is the 1941 crossing of the Atlantic, but earlier crossings from Africa to the Caribbean are also there, as well as contemporary forced sea crossings. The fertile grounds of Paris and Martinique, Surrealism, and Négritude are the background to the libretto. Aimé Césaire’s seminal poem “Cahier d’un retour au pays natal” (“Notebook of a Return to the Native Land,” 1939) is its bedrock. New anti-rational ways of approaching language and image are in play.”

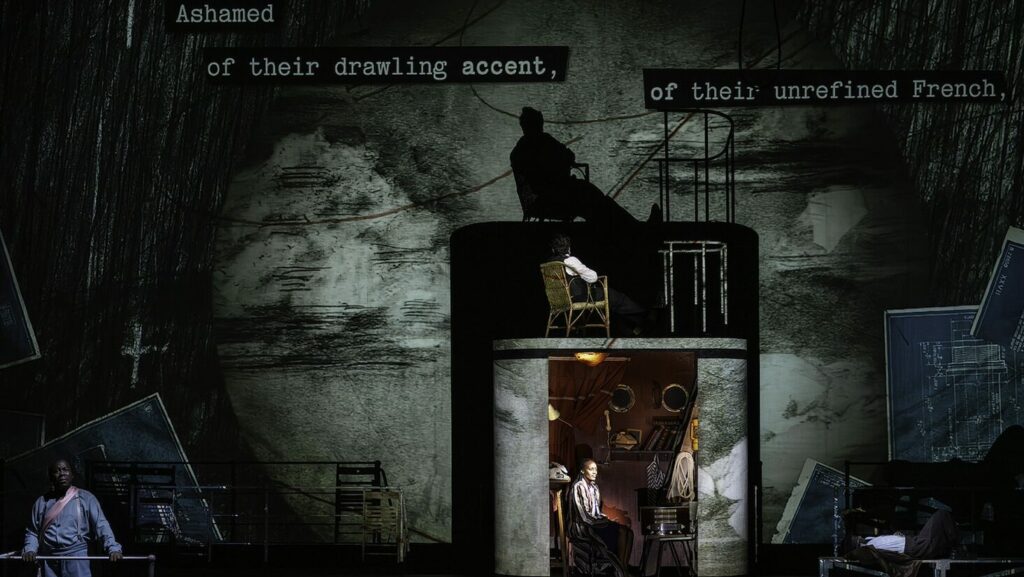

For such a self-described “anti-rational” work, The Great Yes, The Great No felt more coherent than Sybil, where randomness was central to the story. The Capitaine Paul-Lemarle journey provided much-needed narrative context for the scenes and characters. Nevertheless, this was still very much a Kentridge production. His exploration of the relationship between surrealism and the anti-colonial Négritude movement (after all, surrealism had been described as Négritude’s creative weapon) manifested in breathtakingly inventive – if almost borderline extravagant – displays of visuals, combining animated drawings, video projection, masks, shadow play, and bold sculptural costumes with texts and music. The fact that surrealism colored the entire production forced the audience to anticipate surprises lurking around the corner every step of the way.

Part chamber opera/oratorio, part play, The Great Yes, The Great No incorporated many texts, notably from the writings and words of the esteemed passengers, delivered almost as musings or reveries. Dramaturg Mwenya Kabwe, in collaboration with Kentridge, did the heavy lifting in putting all those texts together in an order that somehow made sense. Charon’s words were the clearest examples of this, as they were constructed from many sources, from writings of Breton, Senghor, Suzanne Césaire, Pauline Nardal to snippets from Bertolt Brecht, Anna Akhmatova, and others!

Monika Rittershaus

Speaking of collaborations, in “Surreal Histories” – a conversation between Kentridge and three UC Berkeley professors (Debarati Sanyal, Karl Britto, and Shannon Jackson) before the show on Friday – Kentridge detailed that collaboration was key in the creation of The Great Yes, The Great No. He even shared an anecdote about how he was wary if somebody came to him with a clear idea of contributions.

Nowhere was this more evident than in the choral compositions for the Chorus of Seven Women, the heart of The Great Yes, The Great No. Led by choral composer Nhlanhla Mahlangu (who was also Associate Director of the performance together with Phala O. Phala), the libretto (made up of various texts) was translated into the multiple languages spoken by the seven women (Anathi Conjwa, Asanda Hanabe, Zandile Hlatshwayo, Khokho Madlala, Nokuthula Magubane, Mapule Moloi, Nomathamsanqa Ngoma) and they collaborated in creating the choral compositions that highlighted each strength while harmoniously constructing musical coherence in terms of melody and rhythm. They were inspired by Kentridge’s “poetic phrase:” “The world is leaking – The dead report for duty – The women are picking up the pieces.” The Chorus of Seven Women worked as the gel that bound the narrative of The Great Yes, The Great No together, and their heavenly sound – sometimes sad, other times questioning and hopeful – gave the piece a mysterious and magical ethereal sheen. Xolisile Bongwana sang his heart out as Aimé Césaire, reenacting Césaire’s poem Cahier d’un retour au pays natal with gravitas and expressiveness.

Nevertheless, the driving force behind The Great Yes, The Great No was the four-person band (Marika Hughes on cello, Nathan Koci on accordion and banjo, Thandi Ntuli on piano, and music director Tlale Makhene on percussion) that was present onstage. Not only did they accompany the singers and provide a suitable soundtrack to the narrations and the video projections, but more importantly, they also set the mood for each scene. Makhene was particularly impressive in employing a wide range of sound effects with his choices of percussive instruments!

Monika Rittershaus

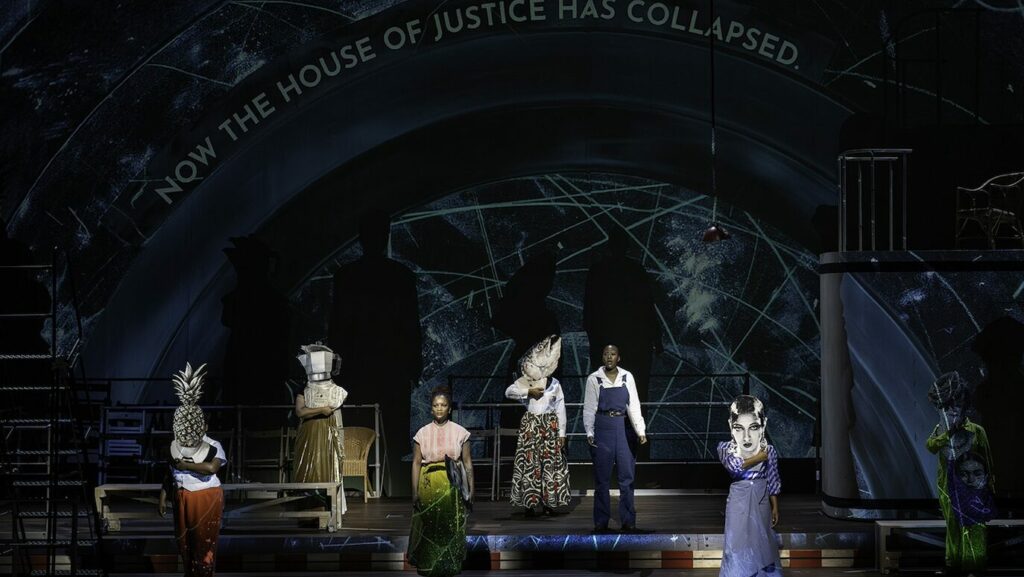

Like Sybil, The Great Yes, The Great No represented an attack on all senses on the visual front. Kentridge brought back many of Sybil‘s creative team members for this production. Set designer Sabine Theunissenreimagined the multilevel stage as a ship deck, complete with a funnel that spun to reveal Pauline Nardal’s salon. A giant screen on the back was used to show all the animations, clips, texts, and video projections, designed by Žana Marovic, Janus Fouché, and Joshua Trappler and controlled by Kim Gunning. Urs Schönebaum and Elena Gui bathed the busy stage with nautical blue/green lights while carefully highlighting a particular scene/performer.

Greta Goiris placed the performers in various absurd and colorful costumes. However, the most striking props on stage were the paper masks of famous passengers – a theatrical device Kentridge first employed in his 2022 film Oh To Believe in Another World (accompanying Dmitri Shostakovich’s Tenth Symphony) – and even hysterical objects like iron coffee pots (iron heads, anyone?), pineapples, or fish heads.

The performers were extraordinarily well-chosen and very committed to presenting Kentridge’s vision. Chief was Hamilton Dhlamini, who personified the central role of Charon with dignity and wittiness in equal measure. Charon here acted not only as the Captain of the Capitaine Paul-Lemarle but also as the story’s narrator, introducing each character and commenting on the proceeding. Interestingly, Charon introduced everybody with a “surrealist” prefix, such as a surrealist poet or a surrealist writer. Dhlamini also produced many of the show’s funniest jokes, which he delivered with great comic timing.

Monika Rittershaus

The rest of the cast played multiple roles with a sense of sophistication, refusing to let each character become a caricature despite the paper masks. It was hard to keep up with who was playing what character, although a few highlights included Nancy Nkusi’s elegant take on Suzanne Césaire and Tony Miyambo’s despair-ridden Fanon. Kentridge also incorporated dances in the presentation, and dancers Thulani Chauke and Teresa Phuti Mojela mesmerized as the dancing duo Josephines (Baker and Bonaparte). Last but certainly not least, William Harding and Neil McCarthy were responsible for many of the show’s most outrageous moments, including the show’s most sarcastic character, the dueling Bretons. (I wonder what Kentridge really thinks of Breton!)

Despite all the brilliance and total commitment from the whole cast, I couldn’t help but think that the show wasn’t perfect. Adopting the format of Charon’s introduction then presenting the character throughout, unfortunately, led to a somewhat episodic nature of the narrative no matter how varied each presentation was. I longed for more insights into the encounters of all those strong characters on the ship, and I didn’t get that from the stage. Luckily, a storm scene near the end (before arriving at Martinique) broke the monotony and generated a thrilling edge-of-seat climax (magically conjured by the musicians), bringing the story to a satisfying conclusion.

On Friday, the whole cast and Kentridge were accorded a well-deserved thunderous round of applause and a lengthy standing ovation from Bay Area audiences, signifying the relevance of the show’s messages, particularly here in the U.S. I do hope this important show will travel further in the future and that it will open more eyes and make more people think!